Displaying items by tag: Eels

Eels Found in Bangor Park Pond During Dredging Work

Eels in a park pond? About 150 eels were found during de-silting work in the ponds in the 37-acre Ward Park in the centre of Bangor on Belfast Lough.

That’s about 5,000 km from their spawning area, the Sargasso Sea in the Western Atlantic. The Eels are better known in Northern Ireland as those associated with the largest wild-caught eel fishery in Europe near Toome in the Northwest corner of Lough Neagh, the largest freshwater lake in the British Isles.

Eels spawn in the Sargasso Sea and the young migrate to the freshwater rivers of Europe as “glass” eels to grow and mature to adult eels, which after a long period (could be up to 20 or more years) they make the journey back to sea to begin the long migration to the Sargasso again.

As reported in the County Down Spectator, the dredging work in the Park revealed the eels, and David Kelly, director with the County Fermanagh-based Paul Johnston Associates Fisheries Consultants, was responsible for relocating the eels to safety while the des-silting was carried out. Mr Kelly told Afloat how that process was carried out. “As each section of Ward Park ponds was due to be de-silted, the eels that were rescued from that section were captured and stored temporarily in basins at the side of the park (only for max. of 30-40mins). Eels were then released into a different part of the Ward Park complex away from the de-silting works. This activity was repeated sequentially around the complex as the contractors de-silted different sections”.

Around 150 eels were rescued over the period of the works.

David Kelly Photo: Paul Johnston Associates

David Kelly Photo: Paul Johnston Associates

Mr Kelly explained further. “Eels generally ranged from about 15cm long to 55-60cm, but we got one around 90cm. Most of the eels were aged from just over a year to perhaps 25-30 years. There is a possibility that the largest were older, but we can only estimate how old.”

It is thought by some locals, that the original eels entered the river system of which the Ward Park ponds are part, via the culvert where the river meets the sea in the corner of Bangor Marina and a member of a local walking group recalls as a child, seeing eels in the river which flows into the upper pond.

More here

Northern Ireland Councillors Call for Action Over Toxic Blue-Green Algae Blooms

Causeway Coast and Glens councillors have echoed growing concerns over the state of the aquatic environment following recent blooms of toxic blue-green algae, as the Belfast Telegraph reports.

Alliance Councillor Peter McCully tabled a motion at last week’s Environmental Services Committee Meeting that emphasised the “detrimental impact these blooms have had on local businesses”.

As previously reported on Afloat.ie, at least one long-standing business on the Lower Bann has announced its closure, claiming its future is “unsustainable” given the likelihood of dangerous cyanobacteria blooms happening “on a yearly basis”.

Cllr MuCully said the response from Northern Ireland’s Department for Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) to this summer’s incidents is “not sufficient” and his motion calls for DAERA to convene cross-party talks across all affected council areas to develop and action plan.

Lough Neagh has also been affected by toxic blue-green algae blooms in recent months, with angling groups claiming that the lough is “dying” due to the affects of pollution from untreated wastewater and agricultural run-off.

The lough’s eel fishermen have added their voices to the call for action, saying their industry has collapsed this season.

"Never have I seen so many eel fisherman resorting to scale fishing in order to make some form of income,” one co-op member told the Irish News, which has more on the story HERE.

Eel Fishing Season on Lough Neagh Begins

The eel fishing season on Lough Neagh began last week. And in a conservation measure, the Lough Neagh Fishermen’s Co-Operative Society was involved in helping restock the Lough with "glass eels" (one and a half million of them), the juveniles of the famous fish species. This is a crucial but very expensive practice, in which the Co-operative has been engaged since the 1980s. At 1760 sq. miles, Lough Neagh is the largest freshwater lake in the British Isles.

Restocking Lough Neagh eels

Restocking Lough Neagh eels

In his pictorial book on the Lough, Brian Cassells tells of what he calls the ‘theoretical’ life story of these slimy, snake-like fish considered to be a fine food delicacy. The young elvers born in the Sargasso Sea off Bermuda are carried 3000 miles on the Gulf Stream ending up in loughs and rivers in Europe. After a journey which can take up to two years some gather in the estuary of the Lower River Bann on the north coast of Northern Ireland and make their way upstream to Lough Neagh aided by special ladders strategically placed at weirs. They will live in the Lough for up to ten years.

According to Cassells, migrating eels are captured at weirs on the River Bann where it leaves Lough Neagh at Toome.

The Lough Neagh Fishermen’s Co-operative has been amongst the forerunners of wild eel producers for decades and is recognised as the largest source of wild-caught eel in Europe, producing around 400 tonnes of eel annually. The eels are mainly shipped to Holland (for smoking) and Billingsgate, London (for production of jellied eel) although eels are for sale locally.

The Co-operative affirms on its website, “We are a Co-operative, protecting the livelihood of fishermen and building a sustainable, viable future for fishing on Lough Neagh”.

Inland Fisheries Ireland Comments on Investigation Into Eels’ Passage of Ardnacrusha Turbines

Inland Fisheries Ireland (IFI) says it would welcome a review of turbine operations at the Ardnacrusha power plant around the peak time for eel migrations.

The statement comes following the publication of its investigation into a report of a fish kill in the lower Shannon last December, allegedly resulting from eels passing through the hydroelectric turbines during Storm Barra.

IFI says a report was received from a member of the public on its confidential hotline late on 8 December, which relayed information seen on social media.

Fisheries officers undertook a detailed investigation during daylight over the next two days, with only one dead eel recovered.

“However, finding only one dead eel may have been due to a variety of reasons,” it says. “For example, there was a time lag between the incident and the reporting of the incident…. Therefore, dead eels may have been taken by predators or are very likely to have been swept further downstream.”

IFI notes the “well-established fact” that the use of hydroelectric turbines such as those used in the ESB plant at Ardnacrusha “results in significant mortalities of eels moving downstream to sea”.

It adds: “In fact, the operation of the turbines at the Ardnacrusha hydroelectric station is estimated to kill over 21% of the total run of down-migrating eels.”

The fisheries body emphasises that it does not have a statutory role in regulating operations at Ardnacrusha, and that fisheries on the River Shannon are owned by the ESB.

“However, Inland Fisheries Ireland would welcome a review of the flow and turbine operations around the time of peak silver eels’ migration. This would improve eel survival rates in the future and improve fish passage generally via the old River Shannon channel,” it says.

The report into this incident can be downloaded below.

Payouts For Former Eel Fishermen In Galway From This Month

Former commercial eel fisherman in Galway will receive compensation up to a maximum of €3 million from this month, as Galway Bay FM reports.

Applications were opened till the end of November for the Support Scheme for Former Feel Fisherpersons which will offer restitution payments to those who were actively engaged in the commercial eel fishery before it was closed in 2009.

More recently, Ireland’s eel fishermen have been involved in a scientific fishery gathering data from key catchments to map out the health of the species around the country.

New Angling Outreach Initiative Reels In Novices In Galway

#Angling - The Outdoor Ranger Tuam Angling Education Programme provides information sessions, skills workshops and fishing excursions to young people who may be interested in trying out the pursuit.

Sean Canney TD, Minister of State with responsibility for inland fisheries, expressed his full support for the Tuam-based programme this week and welcomed the funding from Inland Fisheries Ireland’s National Strategy for Angling Development Fund to support its rollout.

“This programme will encourage and engage young people in angling and allow experienced volunteer anglers from local clubs to pass on their knowledge and skills to the next generation,” Minister Canney said.

“Collaboration such as this is vital to ensure that these skills, developed over many years, are not lost. I am particularly pleased that the Outdoor Ranger Tuam Angling Education Programme is supported locally by Cairde an Chláir working with Inland Fisheries Ireland.”

The programme commenced in October with a strong uptake, and participants enjoyed guest appearances from well-known anglers during the programme.

Nathan Creaven from Kilconly, Tuam who fly-fished for Ireland earlier this year, demonstrated his fly-tying skill, while Owen Trill, and international fly-tier from Galway, gave his own demonstration at one of the skills workshops.

The information sessions and workshops aimed to provide students with the basic skills necessary for recreational angling. Young people took several lessons on several topics including sustaining quality habitats, line rigging, baiting, knot-tying, casting techniques, fish retrieval, fish handling, catch and release, rules and regulations of angling and biosecurity.

In addition, they enjoyed a fishing trip to Oughterard Fishing School where they had the opportunity to put their new found angling skills to practise.

The programme received funding from IFI’s National Strategy for Angling Development Fund. The strategy aims to ensure that Ireland’s angling resource is protected and conserved in an environmentally sustainable manner for future generations to enjoy while also striving to make angling an accessible and attractive pursuit for all.

Suzanne Campion, Head of Business Development at Inland Fisheries Ireland said: “We are delighted to support the Outdoor Ranger Tuam Angling Education Project through our National Strategy for Angling Development.

“It is through partnerships such as this one [in Tuam], where local fishing clubs and associations are working together in a constructive and positive manner, that we will secure the future of our fisheries resource,” said Suzanne Campion, IFI’s head of business development.

Teresa Kelly from the Outdoor Ranger shop in Tuam added: “Learning to become an angler is something we took for granted when we were young. We took our bike out and headed off to the river for the day. But this is a thing of the past and the amount of young people that don’t know anything about angling, or that it’s even a sport, is shocking — especially as we have the finest rivers and lakes at our doorstep.

“This is the issue that the Outdoor Ranger Tuam Angling Education programme wants to highlight and also to make changes by providing information and day trips out fishing with young people to give them to the opportunity to learn and gain a love of angling.”

In other news, applications are open till 5pm this evening (Friday 30 November) for the Support Scheme for Former Eel Fisherpersons.

The fund offers a restitution payment specifically targeted at former licensed eel fisherpersons who were actively engaged with the commercial eel fishery prior to the National Eel Management Plans and the 2008 public consultation which subsequently lead to the closure of the commercial eel fishery.

Details on the scheme are available on the IFI website. Late applications will not be accepted.

Eel Fishermen Celebrated By IFI For Scientific Contributions

#Fishing - Local eel fishermen were celebrated recently at an information day hosted by Inland Fisheries Ireland in Athlone.

The fishermen, who are involved in IFI’s Scientific Eel Fisheries in different parts of the country, attended the event which aimed to provide an update on the progress made through these fisheries and to recognise the contribution of the fishermen to date.

In total, there are 11 fishermen involved in the initiative, with many experienced in fishing for eels over several years.

Since last year, they have provided support to IFI by fishing for eel in a conservation-focused manner with a view to gathering necessary data which will help protect the species into the future.

Their local expertise and historical knowledge around eels in their areaa has given invaluable support to IFI during the set up and delivery of the Scientific Eel Fishery.

IFI commenced the process of setting up a network of scientific fisheries for eel around Ireland in 2016. These scientific fisheries cover the different life stages — glass eel, elver, yellow and silver eel — and are distributed in key catchments around Ireland.

The purpose of the fisheries is to increase the knowledge around eels in Ireland ahead of the next EU review of this endangered species, and to inform the management of eel populations which are currently in decline.

Dr Cathal Gallagher, head of R&D at IFI, said: “This important partnership between eel fishermen and research has one shared objective: to improve our knowledge of the state of the eel populations and to ensure their conservation for future generations.

“Inland Fisheries Ireland appreciates the benefit of citizen science programmes such as this one which will preserve the heritage of eel fishing and at the same time deliver on the research requirements needed to report to the EU. I would like to recognise and thank all the fishermen involved for their support.”

Citizen science is growing in popularity and encompasses many different ways in which citizens who are non-scientists are involved in scientific research projects.

The involvement of fishermen in the Scientific Eel Fisheries plays an important role in respecting the tradition and heritage of eel fishing in Ireland. Many of the fishermen come from families where eel fishing has been practised across several generations with local expertise and knowledge passed down through the years.

Eels from Ireland travel as Far as Azores in New Study

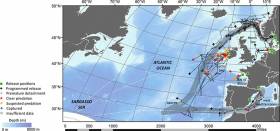

Irish researchers from Inland Fisheries Ireland have contributed to an EU funded research which has helped solve the deepest secrets of oceanic migration and behaviour of one of Europe’s most mysterious fish, the European eel. The international research team, led by the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas) in the UK, tracked more than 700 eels as they made their annual mass migration from Europe to the Sargasso Sea. Over 200 tags were recovered, allowing the scientists to map more than 5,000 kilometres of the migration route.

Ireland was one of four countries alongside Sweden, France and Germany which released eels between 2006 and 2012 for tracking purposes. The study allowed scientists to map migration routes from Europe to the Azores region, approximately half the distance to the area where they spawn in the Sargasso Sea. Forty four eels were successfully tracked from Ireland with pop up satellite tags. This study monitored eels further and longer than any previous research with one of the tags from an Irish eel registering a journey of 6,982 kilometres and 273 days at sea.

The study has overturned previously accepted theories on the European eel which believed that eels made one large journey to the Sargasso Sea, located in the Western Atlantic near the Bahamas, to breed once before they die. This new research shows that their arrival to the Sargasso Sea is more staggered; a finding which will have impact on how this critically endangered species will be managed and conserved in the future.

While some eels do take the quickest route available, travelling from Europe and spawning in early spring within six months of departure, the evidence suggests that the majority of eels undertake a slower paced migration which enables them to arrive in the Sargasso Sea a year later than previously thought. This means that the eels are at sea for longer and exposed to a higher risk of predation and other mortality events.

Dr. Cathal Gallagher, Head of Research and Development at Inland Fisheries Ireland said: “During this programme, Irish eels were released from the Shannon, Corrib, Erne and Burrishoole catchments to make the journey from our freshwaters out into the open ocean to join their European counterparts and cross the Atlantic. While there is still so much we don’t know about this mysterious fish, this research has revealed more than ever before.

The life cycle and migration of the eel continues to puzzle scientists as they are born into and spawn in the remote ocean, making them difficult to study. While previously it was understood that eels travelled to the Sargasso Sea to spawn, we did not understand the duration and the dangers our eels are exposed to during this migration. We now know more also about their behaviour patterns as all eels exhibited diel vertical migrations, swimming though deeper water during the day and moving closer to the surface at night. This understanding of eel biology will help manage and conserve their population across Europe and beyond more effectively.”

The study relied on two different types of tags, ‘pop up’ satellite tags and internal and external data storage tags, to track the eels. Satellite pop up tags are attached to the eel and pop off on a predefined date, automatically transmitting migration data to researchers via a satellite link. The data storage tags, which are bright orange in colour, need to be physically recovered when they float back to land on the tides. Researchers rely on citizens recovering and returning the tag to help them complete their research. To date, 82 data storage tags have been collected and returned by citizens in several countries, including in Ireland.

Dr. Patrick Gargan of Inland Fisheries Ireland was one of the authors on the research article ‘Empirical observations of the spawning migration of European eels: The long and dangerous road to the Sargasso Sea,’ published in science publication Science Advances.

-

Interesting facts about the European Eel:

- The growth stage, known as the yellow eel, takes place in marine, transitional or freshwater and can last from 2 – 25 years depending on the location.

- In Ireland, male silver eels range in age from 5-15 years old with female silver eels ranging from 10-20 years of age. However, eels of greater than 30 years old have been recorded.

- Eels from the southern region of Europe tend to migrate earlier than eels from the northern region with faster growth recorded in warmer waters.

- The male eel tends to migrate at a length between 30 and 40 cm, with females migrating at greater than 40cm in length and reaching one metre in length.

- The male and female eel undertake different life strategies with the male reaching the minimum condition required to undertake the migration and spawn; and as a result migrate at a younger age and smaller size compared with females who try to maximise condition.

- During their migration, eels move to deep water (up to 800m) during the day and into shallower water (-350m) at night. This may be to regulate water temperature, avoid predators or for navigational reasons.

- The longest migration recorded in this study was more than 300 days. Each day the eel made a vertical migration of more than 300 metres and back.

Applications Open For Scientific Eel Fisheries

#Eels - Inland Fisheries Ireland is in the process of setting up a network of scientific fisheries for eel around Ireland.

These scientific fisheries will cover the different life stages (elver, yellow and silver eel) and be distributed in key catchments around Ireland.

The purpose of the fisheries is to increase the data and knowledge of eel in Ireland ahead of the next EU review in 2018 which will help inform management on the state of the eel stocks as part of the Eel Monitoring Programme.

Details of the type of fisheries and the locations is outlined in the application document HERE.

IFI requests that former eel fishermen apply, and include an application specifying which of the locations and life stages they are interested in applying for.

The engagement of services will be a rolling contract – reviewed on an annual basis likely to extend for a period of three years, subject to an annual review and funding.

The research fishery will be authorised with the successful application of a certificate of authorisation under Section 14 of the Fisheries (Consolidation) Act, 1959 as substituted by Section 4 of the Fisheries (Amendment) Act, 1962. IFI will engage with the applicants in relation to the successful operation of the research fisheries.

Any questions in relation to the scientific eel fisheries can be sent by email to [email protected] or in writing to:

Scientific Eel Fishery

Inland Fisheries Ireland,

3044 Lake Drive,

Citywest Business Campus,

Dublin 24

D24 Y265

The closing date for applications is Friday 15 April 2016.

#Fishing - Minister for Natural Resources Joe McHugh has announced a new collaborative research initiative involving Inland Fisheries Ireland (IFI) marine scientists and a number of former eel fishermen to further develop national knowledge of the species and its medium- to longer-term potential for recovery.

Based on management advice from IFI, the existing conservations measures in Ireland’s Eel Management Plan (EMP), agreed by the EU under EC Regulation 1100/2007, will remain in place up to mid-2018.

“IFI has submitted advice and recommendations on Ireland’s EMP in the period 2015-18. These recommendations are cognisant of the independent scientific recommendations from the Standing Scientific Committee on Eels (SSCE) which underline the risk in opening fisheries at this time," said Minister McHugh.

“I am anxious that a scientific fishery involving some of the stakeholders is undertaken for the next three years to increase data and knowledge ahead of further review and I have secured funding to start the research in 2016. This would facilitate a better informed decision on the outlook for the stock over the next few years and beyond and also the prospects for a return to commercial fishing activity.”

The minister also pointed out that IFI would examine the data derived from the new initiative annually and review recommendations on management measures if the research supported this.

While some river basin districts appeared to attain the escapement targets set in the EU regulation, the minister said regulation clearly required attainment of targets over the long term.

“Progress has been made since 2009 when the protection actions were introduced with some rivers basins showing encouraging signs, but we cannot undermine that progress by undoing key conservation measures because we have some green shoots.”

Minister McHugh also emphasised that he fully appreciates the demographics of the former fishermen and the difficulties experienced by them since 2009.

“I want to use the new scientific research to better explore the potential for short to medium term recovery of the fishery and prospects for fishing in the future," he said. "We have put in place measures to protect eel stocks but based on the research outcome I will be better placed to consider the longer term socio-economic impacts on fishermen and communities and what measures it may be possible to put in place for fishermen.”

The measures currently in place under Ireland’s EMP principally involve a cessation of the commercial eel fishery and closure of the market, and mitigation of the impact of hydropower installations.

As previously reported on Afloat.ie, illegal trade in eels is a growing business, with hundreds of millions of young eels taken from France's Atlantic coast to China each year.