Displaying items by tag: Bermuda

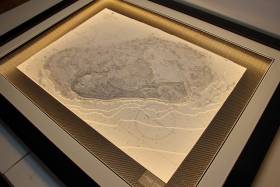

#AmericasCup - Relief chart specialists Latitude Kinsale have been commissioned to create the winners' trophies for the America’s Cup J Class Regatta in Bermuda this month.

Renowned artist Bobby Nash, based in Kinsale in West Cork, created unique 3D charts based on the classic Bermuda Islands map from the UKHO Admiralty archive for the first, second and third prizes in the exclusive regatta for traditional America’s Cup J Class yachts.

The 1950s-era chart shows the archipelago of islands and reefs that comprise the British Overseas Territory in the North Atlantic — the complex structure painstakingly crafted by hand from as many as 2,000 individual pieces.

All three prizes are presented in frames incorporating patent-pending Surround Lighting for optimum illumination of their meticulous details.

“It’s a great honour to be selected as the creator of the overall prizes for the America’s Cup J-Class regatta in Bermuda,” said Bobby Nash. “To have my work appreciated by such a prestigious event and organisation is a reflection of 15 years of experience, design evolution and presentation.”

Latitude Kinsale is renowned worldwide for its soughtt-after 3D charts, framed lighting charts, relief nautical bespoke chart tables and commissions, creating a unique way to appreciate the beauty of the coastline and the sea.

Ben Ainslie's Team Take to The Waters of The 35th America's Cup

#benainslie – Ben Ainslie Racing were the first America's Cup team both on – and under – the race course waters of the 35th America's Cup last week, when the team conducted an initial training camp in Bermuda.

"It's been great for the team to get out on the water, trying to learn about the venue, the wind direction, the wave states in our 20 foot foiling training boats," commented Team Principal and Skipper, Ben Ainslie. "A huge amount has been learnt, and we can now go back to our design team and start working on developing the final race boat for 2017."

"We turned up here with preconceived ideas about everything," added Sailing Manager, Jono Macbeth. "But it's not until you actually step foot on the island that you get a feel for what's going on. It's going to be completely different compared to last Cup where the wind direction was the same every single day. Here we have seen wind from just about every corner.

"We're just learning all the time. It's invaluable that we are here, especially as the first team on this race course. It's a statement that we are serious about the competition ahead of us. The atmosphere here in anticipation of the America's Cup is incredible," continued Macbeth, "Everyone on the island is so into it. This year is just going to fly by."

"Bermuda is just the most beautiful island," said Ben, "the people are so warm and friendly and are really excited about having the America's Cup here. As a sailing venue it is a real challenge, it is such a tight course and the wind is really variable out here in the middle of the Atlantic."

The major objective of the training camp was to learn the local conditions, and raise foiling skills, but Ben Williams, Head of Strength and Conditioning ensured that the Sailing Team got an extensive work out as well.

"It's been great for us as a sailing team to get away," said Ben. "It's almost been a military operation, our fitness trainer is an ex-Marine and pushing us pretty hard in the morning and evenings. And out on the water we have been sailing and training very hard – but bonding as a team, being away and really focusing on sailing and training."

"I really wanted to make sure that we were using our time wisely out there so we are doing two training sessions in the gym and sailing the boats five or six hours every day," said Macbeth. "There's really not a huge amount of time for the boys to do anything except eat, train and go sailing." Williams unique methods included an opportunity to properly test the depths of Bermudian waters

Rumour Mill Says Bermuda Has The Nod For Next America's Cup

#AmericasCup - Though the official announcement is still a week away, speculation is growing that Bermuda will be chosen as host for the 2017 America's Cup.

But as Stuff.co.nz reports, the rumour comes as a major blow to San Diego's hopes of welcoming the event.

It seems the issue is simply down to the matter of money, with a tourism chief from the Southern Californian city quoted as saying that "when it came down to it, Bermuda was the destination Larry [Ellison] needed to choose."

Ellison - head of software giant Oracle - was the backer of the current cup holders Oracle Team USA, which won in spectacular fashion last year.

And the financial incentives of hosting the event in the Caribbean tax haven are hard to ignore, even in spite of San Diego's storied legacy in sailing.

Stuff.co.nz has more on the story HERE.

#cruising - Sailing From Bermuda to the Azores on the magnificent yacht Wolfhound III with skipper and lifelong friend Alan McGettigan was an 1,800–mile adventure for Kildare sailor Fin O'Driscoll.

Bermuda is the oldest remaining British overseas territory and the picture postcard town of St. George on the north east corner of the main island is the oldest continuously inhabited English settlement in the new world writes Fin O'Driscoll. The town dates from 1612, when British naval vessel 'Sea Venture' captained by Admiral Sir George Somers was deliberately steered onto a nearby reef to escape a storm. In 1996, the town was twinned with Lyme Regis, in Dorset, the birthplace of Admiral Somers and in 2000, it was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Three friends and I travelled from Dublin to St. George in early May where we waited a few days for a boat sailing down from Newport, Rhode Island. Having enjoyed sailing over the years such as cruising in the Med, racing in Dublin bay and coastal trips in the Irish Sea, I knew that this was going to be different. An 1,800 mile crossing from Bermuda to the Azores.

Bermuda has a population of 62,000 and the economy is based on offshore insurance and tourism with the territory enjoying the world's highest GDP per capita for most of the last two decades. The islands have a humid sub-tropical climate and are warmed by the Gulf stream with water temperatures reaching a tepid 22C, making it a wonderful place to swim compared to the chilly Irish Sea. Interestingly, a survivor of the 'Sea Venture' shipwreck was one John Rolfe, whose wife and child died and were buried in Bermuda. Later in Jamestown he married Pocahontas (of Disney fame!), a daughter of the powerful Powhatan, leader of a large confederation of Algonquian tribes in coastal Virginia.

Our vessel, Wolfhound III arrived from Newport on 8th May. She is a magnificent yacht, owned and skippered by Alan McGettigan (RIYC), a lifelong friend from Dublin. I am from Kildare and the three other Irish sailors were William Reilly from Greystones, Barry O'Sullivan and John Campbell from Dublin.

Wolfhound III alongside in St. George

Wolfhound III is a classic Nautor Swan 59' sloop, weighing in at 30 tonnes and sporting an 80 foot mast. She has 4 cabins, can comfortably sleep 10 crew and is complete with a large saloon and galley, a myriad of instrumentation and no less than 14 winches plus 2 grinders on deck! A lot of other boats were arriving for the ARC (Atlantic Rally for Cruisers) 2014 race which was due to leave St. George for the Azores on the 14th so the marina was buzzing. Bermuda is a very expensive place to shop, which we soon found out when we completed our provisioning for 2 weeks at a cost of $2,100 and that excluded any alcohol as she was a dry boat!

Leaving St. George heading East

We departed on Sat 10th May at 14:00 in idyllic sailing conditions and enjoyed three days of fine weather, which allowed us get used to the boat, champagne sailing without the champagne! Three of the crew are keen amateur chefs and so we enjoyed fine cuisine on the high seas. As we headed North East to catch the prevailing winds to the Azores, we ran into heavy weather as forecast. We encountered a large low pressure system, so the westerly winds on the south side of the system swept us towards our destination. Barometer readings dropped 15millibars in 6 hours followed by gusts of up to 40knots and 25 foot seas, which made for an exciting and challenging passage.

Alan McGettigan (left) and article author and crew man Fin O'Driscoll

The crew in full offshore gear, wore lifejackets at all times and were strapped onto lifelines while on deck or in the cockpit. At night we were on two hour shifts and as the boat was rolling a lot, the culinary delights from the galley were replaced by storm rations; Campbell's soup, tinned ravioli and copious amounts of Red Bull to keep us alert through the long nights.

The gales lasted five days and with winds averaging 25 knots our trip log recorded us surfing down big Atlantic rollers at up to 15 knots, which is fast for a cruising yacht. As is the norm in these weather conditions the boat is tested to the limit and Wolfhound III performed admirably. The port jib sheet parted when a large bow wave hit the fully unfurled headsail and a full knock down at 05:15 one morning rolled everyone out of their bunks (except the two on watch) however she righted herself very quickly. We learned later that British boat Cheeki Rafiki was in the same storm system 400 miles to the west of us and unfortunately her four sailors were lost when the keel sheared off and she capsized before they could release their liferaft.

Above and below sailing through big seas

In the two weeks at sea, we saw numerous dolphins, porpoises and several breaching whales. The pods of dolphins had a habit of swimming alongside in the early mornings as the sun rose over the bow, a very therapeutic way to start the day. Yes, the Atlantic Ocean is an unbelievably large and empty place as we saw only one other sailboat and three freighters during our voyage. Sailing at night with full canvas up and steering by the stars across the pitch black ocean is an unworldly experience. Combine that with the sparkling luminous green phosphorescence in our wake, a full moon and scudding black clouds for dramatic effect. On day nine, the winds had abated and the sea was millpond calm so we stopped the boat and all dived in (leaving at least one person on board as we had all seen the film Adrift!) for a mid Atlantic swim. A strange sensation considering the nearest land was 2 kms straight down and the nearest coastline was over 1,000 kms away.

Land Ahoy! On day thirteen the Azores appeared on the horizon and we arrived safely in Horta at 19:00, 12 days and 2 hours (including 3 hour time difference from Bermuda) after a distance of 1,900 miles. After tying alongside in the bustling port, we checked in at immigration and immediately proceeded to Peter's Café Sport, a world renowned crossroads and watering hole for transatlantic sailors. The long awaited hot showers had to wait until the following morning as there were celebrations to be had. After 13 days at sea, it took us all a while to get our land legs back and the occasional stumble was not at all due to the pints of Superbock consumed after our dry boat experience.

The happy crew quayside in Horta

Horta on the island of Faial has the fourth most visited marina in the world and is overlooked by the very impressive 2,350m Mount Pico on the neighbouring island. The Azores are a Portuguese overseas territory and the nine main islands stretch over 230 miles from Flores in the West to Santa Maria in the East. Officially, the islands were discovered in 1431 by Portuguese explorer Gonçalo Velho Cabrall and Christopher Columbus famously stopped over at Santa Maria (named after his ship) in 1493 on his way back from discovering the New World. During the 18th and 19th century the islands were host to many prominent figures, including Chateaubriand, the French writer who passed through upon his escape to America during the French revolution and Mark Twain published "The Innocents Abroad" in 1869, a travel book, where he described his time in the Azores. The islands straddle an active junction between three of the world's largest tectonic plates (the North American Plate, the Eurasian Plate and the African Plate) resulting in a lot of seismic and volcanic activity in this region of the Atlantic.

After a memorable night celebrating in Horta, the four of us left Wolfhound III and flew back to Dublin via Lisbon. Following the scheduled crew change, the boat has since sailed the final 850 miles onto Lagos in southern Portugal, completing her full transatlantic crossing from the US mainland to Europe. A real marine adventure and sailing the Atlantic is definitely one for the bucket list!

Irish Yachtsmen Rescued From Stricken Vessel Off Bermuda

#Wolfhound - Four Irish yachtsmen have been rescued from a recently purchased vessel some 70–miles north of Bermuda after it suffered both power and engine failures amid stormy conditions off the northeastern United States.

The 48-foot Swan class sloop Wolfhound, purchased recently by owner/skipper Dalkeyman Alan McGettigan, had departed from Connecticut on 2 February en route to Antigua in the West Indies to compete in the RORC Caribbean 600.

As WM Nixon wrote on Afloat.ie recently, the Wolfhound was expected to eventually call Dun Laoghaire home following its Caribbean adventure.

But according to Bermuda's Bernews website, trouble began when the vessel reportedly suffered a loss of battery power due to the failure of a new inverter charger some 400 miles off the Delaware coast.

This was followed by engine failure a day after departure which left the vessel without communications or navigation systems for eight days.

Between Friday and Saturday the boat reportedly suffered two knockdowns in treacherous weather on the heels of the midwinter storm that recently battered America's northeastern states, and which led McGettigan to activate the on-board emergency beacon.

After a fruitless search by US Coast Guard aircraft, the yachtsmen were eventually located by and transferred to a passing cargo ship, Tetien Trader, which had joined the search effort.

The Wolfhound later sank some 64 miles north of Bermuda.

McGettigan's crew from the Royal Irish Yacht Club in Dun Laoghaire have been confirmed by the club's sailing manager Mark McGibney as Declan Hayes and Morgan Crowe.

Tom Mulligan of the National Yacht Club has been named locally as the fourth crew man on board.

A source close to Afloat.ie says that Hayes telephoned home from the Tetien Trader and confirmed he and the others were being "well looked after" by the Greek crew of the cargo vessel, which is due to land in Gibraltar on 19 February.

A member of the RIYC, Alan McGettigan is an experienced offshore skipper, previously sailing in areas as far afield as the Baltic Sea, the Caribbean, the South China Sea and the Mediterranean, and having competed in past Round Ireland and Dun Laoghaire to Dingle (D2D) races, most recently in the yacht Pride of Dalkey Fuji.

Missing Bermuda Yacht Arrives Safely in Co Kerry

A yacht that was reported missing in the Atlantic between Bermuda and Ireland sailed safely into port in Co Kerry this afternoon.

As previously reported on Afloat.ie, the Golden Eagle has been at the centre of an air and sea search operation since failing to arrive at its expected destination of Crookhaven in Co Cork on 15 September.

The yacht - crewed by a 69-year-old Norwegian and a 60-year-old New Zealander - had been out of radio contact since leaving Bermuda in mid August.

But a spokesperson for the Irish Coast Guard has since revealed that the men intentionally turned off their handheld VHF radio to save battery power until they were close to port.

The boat dropped anchor in Portmagee, Co Kerry at 3pm this afternoon, reporting only minor damage to its sails and rigging due to adverse weather which slowed their progress.

More from RTE here.

Search for Yacht Missing Between Bermuda and Ireland

An air and sea search operation is underway for a yacht missing en route from Bermuda to Ireland, The Irish Times reports.

The Golden Eagle has been out of contact since leaving port on 21 August. It was due to arrive with its two-man crew - a 69-year-old Norwegian and a 60-year-old New Zealander - at Crookhaven in West Cork last Thursday.

The Irish Coast Guard told the Press Association said that the Naval Service and Air Corps are involved in the search off the south west coast, and ships in the mid-Atlantic have also been asked to try to contact the yacht.

The yacht is described as being 9.8m (32ft) long, white and with a blue trim on the side.