Displaying items by tag: Historic Boats

Ireland’s Clinker-Built Boats Lead The Way In New UNESCO Heritage Status

Now hear this, all you sailors or rowers of Greencastle Yawls, Dublin Bay Water Wags, Foyle Punts, International 12s, Shannon One Designs, Castlehaven Ettes, Strangford Lough Clippers, Coastal Hobbler Rowing Skiffs, Dublin Bay Mermaids, Mayfly-Fishing Lakeboats, IDRA 14s, Ballyholme Insects, Classic Ramelton Folkboats and any other boats constructed in what our American cousins would more elegantly describe as the lapstrake method, but we know rather prosaically as clinker-built.

That may sound to the totally uninitiated as something you’d put together from the leftovers in the ashtray of that old heroically-polluting kitchen coke stove upon which the Granny was accustomed to burn the Christmas sprouts long before charred vegetables became – for some inscrutable reason – a favoured item of gourmet dining.

Thus the alternative “clench-built” may be a more accurately descriptive if less-used term to describe this boat-building technique. But either way, the news is that those of you who go afloat in craft built in this way are no longer just going for a race or a sail or a bit of leisurely rowing. On the contrary, you will be engaged in Curating an Item of World Heritage.

This is serious stuff, and Ireland is very much involved in it both through our Dublin Viking boat-building links, and through the Greencastle yawls of the north coast, which were based in the “Drontheim Boats” which were built in Trondheim in Norway – it was the furthest-north Norwegian port with ready access to forest timber - and exported to many northwest Europe ports.

The classic McDonald-built Greencastle Yawl James Kelly, owned by Robin Ruddock of Portrush and seen here sailing under sloop rig on Belfast Lough. She is named in honour of the renowned Portrush boatbuilder James Kelly, who built many traditional clinker yawls in addition to yachts for the Howth 17 and Dublin Bay 21 classes. Photo: W M Nixon

The classic McDonald-built Greencastle Yawl James Kelly, owned by Robin Ruddock of Portrush and seen here sailing under sloop rig on Belfast Lough. She is named in honour of the renowned Portrush boatbuilder James Kelly, who built many traditional clinker yawls in addition to yachts for the Howth 17 and Dublin Bay 21 classes. Photo: W M Nixon

According to the Press Release from our friends in the Viking Ship Museum of Roskilde in Denmark who led the UNESCO campaign, the official story is that:

“The clinker-built boats of the North – and the traditions associated with them – have now been officially acknowledged by UNESCO as living cultural heritage, which must be safeguarded and preserved for future generations”

So far, so good. But if we go further into the Danish release, that all-embracing term “clinker-built boats of the north” very quickly becomes slightly but significantly re-shaped as “Nordic clinker boats”. It’s true enough up to a point. But the reason we’re so familiar with the Viking Ship Museum at Roskilde is because it was they who achieved the re-creation of one of the largest clinker-built boats ever built, the 100ft Viking ship Sea Stallion, which voyaged from Scandinavia for a year-long visit to Dublin in 2007, and picked up awards for our “Sailors of the Month” while they were at it, but that’s another story.

The fact is the original Sea Stallion was actually built in Dublin around 1042, using timber sourced in Glendalough in County Wicklow, which suggests a very real Irish input. Since then, the clinker-built inheritance has been maintained on our north and northwest coasts, where it goes about as far south as Milk Harbour in County Sligo on the West Coast. Meanwhile, on the East and South Coasts, it continued as the preferred method of construction for smaller fishing craft and – in due course – for leisure dinghies and small yachts.

Back where she belongs……the 30 metre Viking ship Sea Stallion on display in Collins Barracks in Dubin in 2007.

Back where she belongs……the 30 metre Viking ship Sea Stallion on display in Collins Barracks in Dubin in 2007.

You only have to look at the beautifully-traditional clinker construction of craft like the McDonald of Greencastle-built yawl James Kelly of Portrush, or a Jimmy Furey of Lough Ree-built Shannon One Design, or a West Cork-built Rui Ferreira of Ballydehob Water Wag, to realise that today, some of the best classic clinker-built construction is happening in Ireland.

We may not have invented clinker boat-building, for no one would argue other than that the classic Viking ship is one of mankind’s most remarkable creations. But we can reasonably claim that in awarding global Heritage Recognition to clinker construction, UNESCO is simply catching up with a state of affairs that has existed in Ireland for very many years. Welcome aboard.

Refurbishing Lough Neagh's Joyce, a World War II Torpedo Recovery Vessel

The charity Silvery Light Sailing based in Newry at the head of Carlingford Lough is passionate about the refurbishment of old boats. One of these is now temporarily berthed in Carlingford Marina on the southern shore of Carlingford Lough. She's a 40-foot naval Torpedo Recovery Boat used during World War 11 on Lough Neagh.

Since the Joyce was sold out of Navy service in 1960, the vessel remained in the same ownership. Gerry Brennan, Chairman of Silvery Light Sailing, was alerted to its Lough Neagh connection by National Historic Ships. The Joyce was built in 1943, and according to the National Historic Ships Register, she was designed by the Admiralty and built by Percy M See at Fareham on Portsmouth Harbour on the south coast of England.

The Joyce during WW2

The Joyce during WW2

The Joyce operated on Lough Neagh from 1943 as a retrieval boat, used during test firing of torpedoes. Since The Joyce was decommissioned, it had been a working boat in Weymouth. She has been refurbished by volunteers at Silvery Light’s Community Workshop at the Greenbank Industrial Estate in Newry.

Gerry explains, "The Joyce was used during World War Two on Lough Neagh to retrieve torpedoes made and tested by the torpedo factory. It will go back to Lough Neagh as part of the Heritage Centre, showing the history and heritage of the Lough. We contacted Lough Neagh Partnership and Antrim Newtownabbey Council, who put it to Councillors who agreed that we secure it for inclusion as an exhibit in the Lough Neagh Heritage Centre". He continued;" Torpedoes were manufactured at the factory at Masserene on the site of a former Army barracks on the northeast corner of Lough Neagh, near Antrim town, and then test-fired from a platform on the Lough. The Joyce would recover them when the engine stopped".

Torpedo Platform Lough Neagh Photo: Tripadvisor

Torpedo Platform Lough Neagh Photo: Tripadvisor

The Torpedo Platform can be seen from the car park at the Lough Neagh Marina in Antrim. It was constructed early in the Second World War so that the torpedoes from the nearby factory could be tested for accuracy of direction and depth. In addition to the launching platform, there were sleeping quarters, a kitchen and food stores in case of weather conditions prevented personnel from returning to their land base. Today the only 'lodgers' are birds such as the common tern and the cormorant.

The Joyce at the Community Workshop

The Joyce at the Community Workshop

Silvery Light Sailing arranged the transport logistics from the UK to the workshop where repairs were carried out and the vessel wholly refurbished. She is fitted with the not so standard Kitchen steering gear, which makes her highly manoeuvrable.

Interestingly Torpedo Recovery boats were also built at Bangor Shipyard on Belfast Lough. During the war, the yard was very busy with Admiralty work and maintained a large fleet of patrol boats and trawlers.

When Belfast Lough's Harbour Of Groomsport Acquired A Scottish Island

Davaar is the conspicuous island at the entrance to Campbeltown Loch on Scotland's Mull of Kintyre, so it was entirely logical that when the local shipping company began to augment their fleet with steamships, the best-known became the Royal Mail vessel Davaar. She was the pride of the fleet and of Campbeltown, but around midday on June 6th 1895, as the morning's thick fog began to lift, the small but well-established maritime community of Groomsport on the south shore of Belfast Lough looked out beyond the low and rocky little Cockle Island which shelters their boats, and found that they seemed to have acquired Davaar.

Had it been the eponymous island, the improvement to the overall shelter of the drying harbour at Groomsport would have been such that it might have been long-since been developed to outperform nearby Bangor. But it was the ship they'd temporarily acquired, and as sailors themselves, the people of Groomsport were entirely in sympathy with the crew of RMS Davaar, as her passenger list seemed to include just about everyone from Cambeltown, all of them - until the impact - happily involved in a much-heralded one-day community holiday outing across the North Channel to Belfast.

Fortunately, they built ships tough in those days. Though the photo by Robert Welch (later to become renowned as the visual recorder of the building of the Titanic) clearly shows that the overall hull structure of the Davaar was undergoing quite severe stress as the tide ebbed, she survived relatively undamaged, while no-one was injured in any way And subsequently – looking as good as new – she continued in the configuration shown here for many years of service under her popular commander, Captain Thomas Muir, who'd been in charge at Groomsport but was later exonerated by an official enquiry.

In fact, Davaar had been so well built that she finished her long life with a newly-fashionable straight stem and just one funnel. But never again did she come a-visiting at Groomsport.

Restored 96-Year-Old Gleoiteog Loveen to be Blessed at Claddagh Basin, Galway Today

Where else in the world would you hear yourself being addressed as Loveen but in Galway - and that's the name of a 96-year-old gleoiteog which is being blessed today (Oct 16) in the Claddagh Basin.

The historic vessel which was built by the Reaneys of Galway’s Spanish Arch was bought from the late Nicky Dolan in 2011 with the support of the former mayor and Labour councillor Niall MacNelis.

It was presented to the Port of Galway Sea Scouts, to help continue the culture and tradition of hooker sailing into the next generation

It has been restored, plank by plank, by expert boatbuilders Coilín Hernon, Ciarán Oliver and a large team from the Galway Hooker Sailing Association (GHSA).

The association, which has over 100 volunteers, began the project in 2019 and continued with careful restrictions through last year’s Covid-19 pandemic.

The Lovely Anne, a late 19th-century gleoiteog, already restored by the GHSA, will join a flotilla today to welcome the Loveen on to the water.

The Port of Galway Sea Scouts and the GHSA are hosting this afternoon’s celebration at Nimmo’s Pier on the Claddagh basin from 2 pm to 4 pm.

Free ticket admission can be obtained on this link here

American sailing photographer Ben Mendlowitz of Maine has been recording classic and traditional wooden boats and their world with an unerring eye for forty years and more now. Apart from regularly contributing to leading magazines, he has had ten books of peerless nautical colour images published. But of all his works, the collection which enthusiasts most eagerly anticipate and treasure is his wall calendar of specially picturesque wooden boats, each recorded with that extra something that gives it the Mendlowitz touch.

The calendar for 2022 is a real milestone, as it's his 40th, and as with the other 39, the stylish matching words are by Maynard Bray. The boats are many and varied, and back in 2009 one of those featured for immortality within the calendar was Hal Sisk's 1894 cutter Peggy Bawn from Dun Laoghaire, recorded in the unmistakable Mendlowitz evening sunlight style during the Sisk crew's visit to the American classic scene in 2008.

However, in the 40th calendar for 2022, Irish classic boat-building has moved up a notch or two. For although Peggy Bawn was Irish-built by John Hilditch of Carrickfergus, she was designed by G L Watson of Scotland. But the November 2022 calendar star is also featured on the cover, and she is Mavis, the 39ft yawl designed and built by John B Kearney in Dublin in 18 very concentrated months in 1923-25 in a corner of Murphy's Boatyard in Ringsend, working in his spare time by the light of oil lamps with no access to power tools.

"From the moment she was launched, it was clear that Mavis was very special…." Mavis winning Skerries Regatta in 1928 with John B Kearney in command. Photo: Courtesy Ronan Beirne

"From the moment she was launched, it was clear that Mavis was very special…." Mavis winning Skerries Regatta in 1928 with John B Kearney in command. Photo: Courtesy Ronan Beirne

From the moment she was launched, it was clear that Mavis was a very special classic. And with her Centenary approaching, classic and traditional boat-builder Ron Hawkins of Brooklin in Maine has somehow carved out enough of his own time to do her justice with a 15-year-restoration which has brought the Mavis spirit back to life.

For in her days of John B Kearney ownership from 1925 until 1952, no regatta on the East Coast of Ireland was complete unless Mavis was present. And her performance as an offshore racer was so impressive that in 1935, Humphrey Barton – the founder in 1954 of the Ocean Cruising Club – applied his engineering and naval architectural skills to analysing the performance of Mavis, and concluded that she sailed above everything that the theories of the day would have expected of her.

John B Kearney (1879-1968) working on the designs of the 57ft Helen of Howth at the age of 83 in 1963. Photo: Tom Hutson

John B Kearney (1879-1968) working on the designs of the 57ft Helen of Howth at the age of 83 in 1963. Photo: Tom Hutson

That said, there is one unmeasurable aspect of sailing Mavis that Ben Mendlowitz has successfully captured. It's the sheer exuberant joy of being aboard her in a breeze she likes, and it's clear from the photo that in the cockpit, Ron Hawkins and his shipmate Denise Pukas are in a seventh heaven as Mavis gives of her best.

"A lot done, a lot more to do" – Ron Hawkins in the stripped-out Mavis at mid-restoration. Photo: Tim Magennis

"A lot done, a lot more to do" – Ron Hawkins in the stripped-out Mavis at mid-restoration. Photo: Tim Magennis

That said, there's a certain sweet sadness in this image, as the boat abeam to weather - the traditional 50ft cutter Vela of 1996 vintage - was designed and sailed for 25 years by Ron's brother, Captain Havilah Hawkins Jnr.

In addition to introducing people to classic sail, Vela did much good work in strengthening the links between sailing and mental health programmes. But now with the passage of the years, she has been sold to Portland, a hundred miles away. This is therefore one of the last times Vela and Mavis were together, so visibly sharing the joy of sailing. Yet there's something that suggests that with Vela now beyond the horizon, Mavis will find an additional and very worthwhile purpose in her remarkable life.

Secret of speed? As Ron Hawkins' restoration of Mavis nears completion, it's clear that her stern - while apparently of canoe form - is in fact a skilfully-disguised and very swift classic counter. Photo: Denise Pukas

Secret of speed? As Ron Hawkins' restoration of Mavis nears completion, it's clear that her stern - while apparently of canoe form - is in fact a skilfully-disguised and very swift classic counter. Photo: Denise Pukas

French Classics Succeed in Keeping a Muted Flag Flying at annual Voiles de Saint-Tropez

You might well think that trying to stage the annual sailing classics megafest of the Voiles de Saint-Tropez without the usual razzmatazz is about as likely to succeed as an attempt to stage Wagnerian Grand Opera in a low key manner. But what with pandemic restrictions and the recent ferociously destructive and sometimes fatal storms in southeast France and northwest Italy, the mood in the area was distinctly subdued. So as several sailing events have already discovered in this annus horribilis, the best thing to do was to simply quietly stage the event, and then let the photos circulate gently afterwards.

With some quality and very expensively restored classics being sold off this year at knockdown prices, it was feared that the sailing world might have passed Grand Classics peak, something exacerbated by the fact that the vital charter market is barely ticking over, if at all.

While the tone was muted, the mood of après sailing in St Trop was still to be found. Photo: Gillles Martin_Raget

While the tone was muted, the mood of après sailing in St Trop was still to be found. Photo: Gillles Martin_Raget

But despite that, there was a varied showing at St Trop, the always impressive images capture the flavour of it all, and while the après sailing was discreet and sometimes socially distanced, it was après sailing nevertheless. And in a year starved for the sight of sails, the boats looked lovelier than ever, while those who incline towards something more modern were also well catered for, with the latest designs of Wicklow-based mark Mark Mills featuring as usual at the front of the fleet.

One local claimed that the controlled but undoubted success of the event for the times that are in it was due to some very earnest praying to St Tropez himself on his feast day, September 31st, around which time the Voiles dates were centred.

To those pernickety folk who would point out that there's no such date as September 31st, we can only respond by saying that there's no such holy man as St Tropez either. Nevertheless, you can find his image in positions of veneration on some of the walls around an entertaining little port which more often than not seems itself to be a figment of the imagination.

Back to the classic sailing, and a decent breeze making in from seaward. Photo Gilles Martin-Raget

Back to the classic sailing, and a decent breeze making in from seaward. Photo Gilles Martin-Raget

West Cork Mini-Workboat Was a Key Link in Ilen's South Atlantic Shepherd Role

When we contemplate the 56ft 1926-vintage Limerick ketch Ilen today in her superbly-restored form, making her stylish way along rugged coastlines and across oceans on voyages of cultural and trading significance between places as evocative as Nuuk in West Greenland and Kilronan in the Aran Islands, we tend to forget that for 64 years this Conor O'Brien-designed Baltimore-built ketch worked very hard indeed as an unglamorous yet vital inter-island link in the Falklands archipelago.

In that rugged environment, she was, of course, the inter-island passenger boat. But she could also be relied on to bring urgently-needed supplies - including medicines - to some very remote settlements, and a regular commuter on board was the "travelling schoolteacher", who was the only link to structured education for the children of families running distant island sheep-stations.

With many islands lacking proper quays, the Ilen's punt was an essential part of the sheep delivery route. Here, it's 1974, and Ilen skipper Terry Clifton starts the Seagull outboard while Gerald Halliday (forward) holds Ilen's chain bobstay, and third crew Stephen Clifton finds it is standing room only among the paying passengers. Photo courtesy Janet Jaffray (nee Clifton).

With many islands lacking proper quays, the Ilen's punt was an essential part of the sheep delivery route. Here, it's 1974, and Ilen skipper Terry Clifton starts the Seagull outboard while Gerald Halliday (forward) holds Ilen's chain bobstay, and third crew Stephen Clifton finds it is standing room only among the paying passengers. Photo courtesy Janet Jaffray (nee Clifton).

But while the people were important, ultimately the sheep were what it was all about, such that from time to time Ilen Project Director Gary Mac Mahon receives historic photos which underline this aspect of Ilen's working life.

And in case there had been any doubt about it, after Ilen was shipped back to Ireland in November 1997, she spent the winter in the Grand Canal Basin in Dublin being prepared to sail back to Baltimore in the early summer of 1998, a target which was met.

But, as ruefully recalled by Arctic ocean circumnavigator and traditional boat enthusiast Jarlath Cunnane of Mayo, one of the volunteers who worked on Ilen through that winter, the toughest and most necessary job had nothing to do with setting up the rig. On the contrary, it was the removal of the accumulated and impacted evidence of 64 years of ovine occupation from the hold.

Ilen in the Falklands at George Island jetty in 1948, with the punt astern. The photo is by John J Saunders, who was the "Travelling Teacher" among the islands

Ilen in the Falklands at George Island jetty in 1948, with the punt astern. The photo is by John J Saunders, who was the "Travelling Teacher" among the islands

Ilen as we know her today, stylishly restored and seen here sailing off the coast of Greenland, July 2019. Photo: Gary Mac Mahon

Ilen as we know her today, stylishly restored and seen here sailing off the coast of Greenland, July 2019. Photo: Gary Mac Mahon

Yet being in that hold or on deck was only part of it for the sheep in their travelling around the islands, for many of those islands lacked proper quays. So in getting the sheep ashore, it was often vital to have a handy, robust and seaworthy ship's punt which – like Ilen herself - had to be versatile in moving easily when lightly laden, while still being more than capable when heavily laden with stores and sheep and people, and often all three together.

Ilen and her punt, with a float of kelp drifting past in classic Falklands style. While the little boat may look ruggedly workaday, there's real functional elegance here, with the transom well clear of the water to allow ease of progress when un-laden, allied to proper load-carrying power

Ilen and her punt, with a float of kelp drifting past in classic Falklands style. While the little boat may look ruggedly workaday, there's real functional elegance here, with the transom well clear of the water to allow ease of progress when un-laden, allied to proper load-carrying power

Among the islands of West Cork, traditional punts like this were developed to a high standard, their basic design modified in line with their planned purpose. Thus when Darryl Hughes with the restored Tyrell of Arklow 1937-built 43ft gaff ketch Maybird sought an elegant yacht's tender, he took Maybird to Oldcourt so that boatbuilder Liam Hegarty – the restorer of Ilen – could create a bespoke punt in the classic Hegarty style to fit Maybird's available deck space.

In going to such trouble to get the ideal boat, Darryl Hughes was in a sense following in the footsteps of Erskine Childers back in 1905, when Colin Archer was building Asgard for Erskine & Molly Childers. Childers went into extraordinary detail about the final form they required for Asgard's tender, as he felt that he and Molly would want to sail the 10ft boat on mini-expeditions in remote anchorages.

The resulting little charmer of a boat had such character – judging by the historical photos - that after John Kearon had completed the conservation of Asgard in Collins Barracks, round the world sailor and former dinghy champion Pat Murphy said she needed her dinghy, and he raised funds around Howth so that Larry Archer of Malahide could re-create the Colin Archer dinghy, which now nestles under Asgard herself in the museum.

Molly and Erskine Childers in Asgard's specially-designed 10ft tender

Molly and Erskine Childers in Asgard's specially-designed 10ft tender

The Larry Archer-built replica of the Asgard dinghy nestles under the ship herself in Collins Barracks, as conservationist John Kearon explains how the preservation work was done to a group of cruising enthusiasts. Photo: W M Nixon

The Larry Archer-built replica of the Asgard dinghy nestles under the ship herself in Collins Barracks, as conservationist John Kearon explains how the preservation work was done to a group of cruising enthusiasts. Photo: W M Nixon

But while Asgard and Maybird's dinghies are fairly light little things which wouldn't be expected to carry excessively heavy loads, when Ilen headed south for the Falklands in 1926, it seems that she took with her a classic working version of the West Cork punt, robust yet sweet of line.

As with all working boats, the ultimate secret is in the stern and the basic hull sections. A straight-stem bow is a fairly straightforward design challenge, but the hull sections amidships have to resist the temptation to be completely round – you need a bit of floor for stability – while most importantly of all, the transom has to sit well clear of the water when the boat is lightly laden, as this makes her easy to row at a reasonable speed with just one or two onboard.

In fact, purists would argue that in a rowing dinghy as in a sailing boat, any immersion of the transom when un-laden is a design fault, as it results in a wake like a washing machine when the boat is moving, instead of letting her slip effortlessly along leaving barely a trace.

A very hard-worked little boat. Ilen's punt gets a brief rest on deck as the mother-ship powers through a typically blustery Falklands day in the 1940s.

A very hard-worked little boat. Ilen's punt gets a brief rest on deck as the mother-ship powers through a typically blustery Falklands day in the 1940s.

The most remarkable example of a successful achievement of this is with the traditional Thames sailing barge whose hull, in the final analysis, is simply a rectangular box pointed at the front, but with an exceptionally clever transom at the stern which takes shape as the hull lines rise at an optimum angle.

The Ilen work tender had no need of such sophistication in its lines, but nevertheless, there's a rightness about the way that transom sits clear of the water, the half-moon out of the top telling us that once upon a time it was handled by someone who knew how to scull, even if in later years the preferred means of propulsion was with a vintage Seagull outboard motor.

Either way, those hardy sheep eventually reached their destination, and the Ilen continued to work her way into the hearts of the islanders such that today, the former members of her crew and their descendants, and those who travelled among the islands aboard this versatile ketch, continue to find old photos that remind us and them of her past life, emphasising how remarkable it is that she has been able to take up her current role as Ireland's only example of a former sail trading ketch.

Homeward bound. With sheep, stores and people delivered to the islands, Ilen with her punt aboard heads through Falklands Sound under the late Terry Clifton's command. Photo courtesy Janet Jaffrey (nee Clifton).

Homeward bound. With sheep, stores and people delivered to the islands, Ilen with her punt aboard heads through Falklands Sound under the late Terry Clifton's command. Photo courtesy Janet Jaffrey (nee Clifton).

Ireland's Classic & Traditional Boats Give Us Hope in Challenging Times

In this time of increasing uncertainty with its frustration of sailing plans, we find reassurance in soothing thoughts of well-restored or new-built classic boats. And traditional vessels in handsome and workmanlike order have the same heartening effect. We've an instinct for properly-used and sensibly-deployed timber in our DNA, for in prehistoric times, it was a significant survival asset. Now, it reminds us of the need for patience, and we find comfort in clichés, not least in the old chestnut that when God made time, he made a lot of it.

For time can be a matter of the greatest importance with the restoration of classics. This month, John Kearney's great Mavis – built in Ringsend in Dublin in 1923-25 - is sailing again in Maine, after a restoration which has lasted very many years. And in so doing, she and those who have brought her back to life remind us of how much has been achieved in recent times to preserve and restore Ireland's historical boats. Perhaps most encouragingly of all, they've been restored not as lifeless museum pieces, but rather as vigorous members of the nation's active fleet, providing inspiring sailing and some excellent racing sport.

Mavis as she will be when her sails have become a complete suit. It is 1928, Mavis has been completed for three years, and she is seen here with Skipper Kearney in full command, sweeping into the finish before an appreciative audience to win Skerries Regatta. For twenty-five years, Skipper Kearney and Mavis were regarded as star turns on Ireland's East Coast, with a formidable record in both inshore and offshore racing. Photo: Courtesy Ronan Beirne

Mavis as she will be when her sails have become a complete suit. It is 1928, Mavis has been completed for three years, and she is seen here with Skipper Kearney in full command, sweeping into the finish before an appreciative audience to win Skerries Regatta. For twenty-five years, Skipper Kearney and Mavis were regarded as star turns on Ireland's East Coast, with a formidable record in both inshore and offshore racing. Photo: Courtesy Ronan Beirne

But before we delve into the new life which is being found for wooden one-design classes and other special vessels of very varying vintages, we must pay our respects to John B Kearney, and to Ron Hawkins and Denise Pukas and their friends and helpers in Camden in Maine, who have patiently brought Mavis back to life. They've progressed the work as time and resources become available, for Ron is a master shipwright from a noted maritime family, and his skills are much in demand by others.

In its Dublin way, John B Kearney's Ringsend background superficially seems not to have been so very different, yet his was a life which would have been remarkable by any standards, in any place, at any time. For in the Dublin of its era, this was a life of astonishing achievement against all the odds in a rigidly structured society made even more conservative by a time of global unrest and national upheaval.

Yet here was a largely self-taught young many who was to design many boats – including the Dublin Bay Mermaid in 1932 – who quietly yet steadily progressed with his zest for life undimmed – he was still designing boats in his eighties – while the respect he received in the sailing world was such that he was a Flag Officer of the National Yacht Club in Dun Laoghaire – for he had long since moved from Dublin city to Monkstown – for the last 20 years of his life.

The eternal enthusiast. John B Kearney, aged 83, at work in 1963 on the plans of his largest yacht, the 53ft Tyrrell of Arklow-built Helen of Howth

The eternal enthusiast. John B Kearney, aged 83, at work in 1963 on the plans of his largest yacht, the 53ft Tyrrell of Arklow-built Helen of Howth

John Breslin Kearney (1879-1967) was born of a longshore family in the heart of Ringsend in Dublin, the eldest of four sons in a small house in Thorncastle Street. The crowded old houses backed onto the foreshore along the River Dodder in a relationship with the muddy inlet which was so intimate that at times of exceptional tidal surges, any ground floor rooms were at risk of flooding.

But at four of the houses, it enabled the back yards to be extended to become the boatyards of Foley, Murphy, Kearney and Smith. Other houses on Thorncastle Street provided space for riverside sail lofts, marine blacksmith workshops, traditional ropeworks, and all the other long-established specialist trades which served the needs of fishing boats, and the small vessels - rowed and sailed - with which the hobblers raced out into Dublin Bay and beyond to provide pilotage services for incoming ships.

And increasingly, as Dublin acquired a growing middle class with the burgeoning wealth of the long Victorian era, the little boatyards along the Dodder also looked after the needs of the boats of the new breed of recreational summer sailors.

The young John Kearney was particularly interested in this aspect of activity at his father's boatyard, where he worked during time away from school. From an early age, he developed a natural ability as a boat and yacht designer, absorbing correspondence courses and testing his skills from 1897 onwards, when he designed and built his first 15ft sailing dinghy, aged just 18.

In adult life, during the day he worked initially as a shipwright in Dublin Port & Docks, but his skills could be so broadly applied that he rose rapidly through the ranks to become involved in the work of many departments, such that by the time of his retiral in 1944, while he was officially the Superintendent of Construction Works, in reality, he was the Harbour Engineer, yet couldn't be so named as he had no university degree.

However, this lack of an official title left him unfazed, for his retirement at the age of 65 meant he could concentrate full-time on his parallel career as a yacht designer, something that was so important to him that when his gravestone was erected in Glasnevin in 1967, it simply stated: John Kearney, Yacht Designer.

The Skipper – John Kearney, in the companionway of Mavis, keeps an eye on the making breeze in Dun Laoghaire on a Saturday afternoon in the summer of 1950. Photo: Richard Scott

The Skipper – John Kearney, in the companionway of Mavis, keeps an eye on the making breeze in Dun Laoghaire on a Saturday afternoon in the summer of 1950. Photo: Richard Scott

Born again. The restored Mavis at anchor in Maine, September 2020. Photo: Denise Pukas

Born again. The restored Mavis at anchor in Maine, September 2020. Photo: Denise Pukas

That he was also a master boatbuilder who had been able to design and build fine yachts in his spare time isn't stated, but over the years he created many, and the 38ft Mavis for himself in 1925 was a masterpiece, with an astonishingly good performance which was such that after racing unsuccessfully against John Kearney and Mavis in a stormy offshore race in the Irish Sea in 1935, Humphrey Barton – who later founded the Ocean Cruising Club in 1954 - was moved to write an article for Yachting World drawing attention to this relatively unsung sailing star from Dublin Bay.

John Kearney's determination to be a full-time yacht designer after his retirement was such that in 1951 he sold Mavis to Paddy O'Keeffe of Bantry, as his yacht design clients expected him to sail part of each season in their new Kearney-designed boats and Mavis wasn't getting the use she deserved. She returned briefly to Dublin Bay in 1956 in the ownership of Desmond Slevin, a ship's doctor who was given a lucrative posting in the US, so he had Mavis shipped across the Atlantic, and she has been New England-based ever since.

She has been both lucky and unlucky in her time in America. Lucky in that there has always been someone who recognised that there was something special in this characterful boat that made her worth preserving. Yet unlucky in that it was never someone with the substantial resources to restore her completely to the classic yacht standards to which John Kearney has so skillfully and painstakingly built her, for such people put their wealth into recognised brands such as Herreshoff, Fife, Sparkman & Stephens, and John Alden.

A lot done, and much more still to do. Ron Hawkins in the stripped-out hull of Mavis. Photo: Tim Magennis

A lot done, and much more still to do. Ron Hawkins in the stripped-out hull of Mavis. Photo: Tim Magennis

Yet the fates were kind in letting Ron Hawkins see the spark that might be found in Mavis, and many years ago he took her over with the intention restoring her as time and funds became available from his work as a master shipwright. It was bound to be a long time, as the rising enthusiasm for classic and traditional craft kept him busy - sometimes until late into the night - at the waterfront boatyards. But he moved Mavis to a workshop on the outskirts of town and started the long process of stripping her out and gradually bringing her back to John Kearney standards, with the supportive arrival of Denise Pukas boosting his enthusiasm for a quality project which at times looked like it might stretch into infinity.

The restored Mavis, newly-launched in 2015, with Don O'Keeffe (nephew of Paddy O'Keeffe) on the tiller in the cockpit with Denise Pukas, and Ron Hawkins in the inflatable

The restored Mavis, newly-launched in 2015, with Don O'Keeffe (nephew of Paddy O'Keeffe) on the tiller in the cockpit with Denise Pukas, and Ron Hawkins in the inflatable

The inevitable hiatus. Mavis awaiting her spars and sails

The inevitable hiatus. Mavis awaiting her spars and sails

Regular readers of Afloat.ie will know that the restored Mavis was finally put in the water in Camden in 2015. Yet with a boat and rig like this, much remained to be done, and always there were the demands of other income-generating projects. Thus it wasn't until the pandemic loomed over the horizon that boatyard work slackened, and there was an unexpected time in the Spring of 2020 to complete the mast and rigging, and get it stepped.

Even when doing it yourself to the extent – as Ron did – of personally making the gaff-boom leather saddle, it's still costly when you're doing it to top Kearney standards, as the best of materials are expected. And though we were receiving photos through the summer of the mast being stepped and dressed, the cryptic attached message said no more than: "Still waiting for the mainsail".

In late summer 2020, the new mainsail finally arrived. Photo: Denise Pukas

In late summer 2020, the new mainsail finally arrived. Photo: Denise Pukas

Thus it seemed that the Mavis sailplan was being assembled from bits and pieces, whereas a full-blown high-budget project would rely for the final effect on a very complete sailplan, such as Mavis was showing in style at Skerries regatta in 1928.

Be that as it may, early in September, we received an untitled snap showing the mainsail finally in place, other photos arrived showing her taking her first tentative steps under main and jib, and then today's header photo arrived showing Mavis making effortless knots under a slightly eccentric rig derived from several sources, with a high-flying jib which in time may well become the jib topsail in the complete version.

When you've been undertaking a major restoration ashore and afloat with close personal involvement at every stage, it's quite a step from working to actually sailing, which is why in the traditional world there was a clear demarcation between builders and sailors. Thus it has taken a little while to become accustomed to the fact that the Mavis which everyone has known for years as something steady and secure in the workshop, or sitting serenely afloat in the Inner Harbor in Camden, is now a living thing which heels as her sails fill with power, and the sound of the sea chuckles past her easily-driven hull as she lifts to the waves.

But in that lovely Fall weather with which Maine is often blessed, they've been getting about, and a visit across to Eggemoggin Reach saw greetings from legendary photographer Benjamin Mendlowitz and a brief vid and immediate fame on his Instagram page. It tells us much about the easily-driven hull that John Kearney gave Mavis, as he gave her the most subtle set of lines with sweeping sheer and double curves in just about every direction to produce the boat that Humphrey Barton particularly recognised as being at one with the sea.

Benjamin Mendlowitz's glimpse of Mavis as published on Instagram

This elevation of the restored Mavis into a place in sailing's Hall of Fame is a timely reminder of the many other Irish projects – accelerating in number in recent years – which have paid the proper respect to Ireland's finest classic yachts and traditional boats by restoring them to full seagoing strength.

It's now a long time since Nick Massey began the restoration of the Howth 17s in 1972, a baton since taken up by Ian Malcolm, while across in Dun Laoghaire Hal Sisk was into an early episode of what has now become an epic tale beginning with the tiny Fife cutter Vagrant of 1884 – he restored her for her Centenary in 1984 – while also being involved with reviving the Water Wags, raising the profile of the Bantry Boat, restoring the 1894 Watson 36-footer Peggy Bawn with Michael Kennedy of Dunmore East for international stardom in 2005, and most recently bringing the Dublin Bay 21s back to life with the hugely-talented Steve Morris of Kilrush, a project also involving Dan Mill.

Hal Sisk's 1894-built Peggy Bawn – seen here sailing at Glandore Classics - set a new standard for authentic restoration in 2005

Hal Sisk's 1894-built Peggy Bawn – seen here sailing at Glandore Classics - set a new standard for authentic restoration in 2005

Other groups had already taken on the very major project of a new life for the Dublin Bay 24s, and while it was a complex scheme which proved painful for some, the innate quality of the original Alfred Mylne design has shone through. Periwinkle is now in pristine restored condition in Dun Laoghaire, Zephyra is nearing re-completion at the ApprenticeShop in Maine (where they're also building a Water Wag), and Arandora is entering a re-build project in St Nazaire where Mike Newmeyer of Skol ar Mor has been commissioned to create a new boat-building school.

But we don't have to go abroad for classic boat-building skills, as Dougal McMahon of Athlone has taken on the mantle of the late Jimmy Furey – legendary builder of Shannon One Designs – and is currently restoring the 1930-built Water Wag Shindilla, a boat with long links to the Falkiner and Collen families, while down in West Cork Rui Ferreira has shown himself on top of the job in building in clinker for the Castlehaven Ette class, the International 12s, and the Water Wags, while being equally adept in putting a new teak deck on the Howth 17 Deilginis.

Thriving in various forms since their foundation in 1887, the Dublin Bay Water Wags currently number 50 registered boats in racing condition

Thriving in various forms since their foundation in 1887, the Dublin Bay Water Wags currently number 50 registered boats in racing condition

Nearby, Tiernan Roe has taken on a variety of skilled work and is currently linked to the re-build of the O'Keeffe family's Lady Min (designed and built by Maurice O'Keeffe of Schull in 1902), while round the corner in Oldcourt on the Ilen River above Baltimore, Liam Hegarty is the sure and steady presence who restored the Ilen herself through a time-scale which rivals the re-birth of Mavis, and while as ever he's distracted by urgent work needing doing on fishing boats, the re-build of Conor O'Brien's Saoirse is proceeding steadily in the Top Shed with the hull caulked and the spars currently being made.

Irish craftsmanship sails the Arctic….the Baltimore-built Trading Ketch Ilen of Limerick in Greenland, July 2019. Photo: Gary Mac Mahon

Irish craftsmanship sails the Arctic….the Baltimore-built Trading Ketch Ilen of Limerick in Greenland, July 2019. Photo: Gary Mac Mahon

The distinctive shape of Conor O'Brien's world-girdling Saoirse continues to re-emerge at Oldcourt in West Cork, as seen yesterday (September 18th). The poop deck and the familiar main deck and coachroof are taking shape, while the hull has already been caulked. Photo: Paddy Hegarty

The distinctive shape of Conor O'Brien's world-girdling Saoirse continues to re-emerge at Oldcourt in West Cork, as seen yesterday (September 18th). The poop deck and the familiar main deck and coachroof are taking shape, while the hull has already been caulked. Photo: Paddy Hegarty

Along the south coast beyond Kinsale in Nohoval is Cork Harbour sailing's best-kept secret, Walsh Boat Works, where Jim Walsh creates classic finishes to Chippendale standards for quality craft such as Pat Murphy's charming Colleen 23 Pinkeen and the International Dragon Fafner. The latter is currently on the market for anyone seeking a top entry boat to join that special group of classic Dragons in Glandore which, back in July, helped the great Don Street celebrate his 90th birthday.

How about that then? The immaculate deck of the restored classic Dragon Fafner as she emerged from Walsh Boatworks of Nohoval. Photo Dan O'Connell

How about that then? The immaculate deck of the restored classic Dragon Fafner as she emerged from Walsh Boatworks of Nohoval. Photo Dan O'Connell

Jim Walsh is also making input into another significant Cork harbour yacht restoration which will see the light of day in due course, but meanwhile, his involvement with Dragons is a reminder that the interest in restoring them is reflected up north, where a secret workshop near Ballyhornan beside the entrance to Strangford Lough has seen the Dragon Skeia superbly restored, and they're now working on a very special bit of Irish Dragon history, the late great Jock Workman's Dalchoolin which is being restored to former glory after her hull and keel were retrieved from two different locations.

You wouldn't expect to find worthwhile restoration projects in a shiny showroom – this is the legendary International Dragon Class Dalchoolin being unearthed in multi-purpose premises on the Ards Peninsula in County Down. Photo: James Nixon

You wouldn't expect to find worthwhile restoration projects in a shiny showroom – this is the legendary International Dragon Class Dalchoolin being unearthed in multi-purpose premises on the Ards Peninsula in County Down. Photo: James Nixon

On closer examination, Dalchoolin proved to be eminently restorable, and the work is now under way. Photo: James Nixon

On closer examination, Dalchoolin proved to be eminently restorable, and the work is now under way. Photo: James Nixon

This leap from Cork Harbour to Strangford Lough seems to leave the East Coast and Dublin in particular devoid of the classic skills, but they're there in Arklow if you know whom to seek, while in Dublin, there's Larry Archer's impressive record in restoring boats with Ian Malcolm of the Howth 17s and the Water Wags, particularly impressive in that Larry can somehow find a flicker of life in a very damaged boat which others might have been too ready to write off as a total loss, while in Howth Johnny Leonard worked wonders in bringing the Bourke family's L Class Iduna back to better-than-new condition.

The L Class Iduna's restoration by Johnny Leonard created a little classic glowing with health. Photo: W M Nixon

The L Class Iduna's restoration by Johnny Leonard created a little classic glowing with health. Photo: W M Nixon

As for traditional craft, the great Clondalkin-built Galway Hooker Naomh Cronan need skilled work done before she was moved to her new home in Galway city, and the job was done in style in Malahide by Donal Greene whose credentials are unrivalled, as he's from Connemara, he's descended in a long line from natural boatbuilders whose skills he manifests, and yet he has an enviable affinity for working with computers when planning how best to utilise the available amount of timber for a specific job.

Guy & Jackie Kilroy's Marguerite, a Herbert Boyd design built in Malahide in 1896, is a restoration by Larry Archer

Guy & Jackie Kilroy's Marguerite, a Herbert Boyd design built in Malahide in 1896, is a restoration by Larry Archer

We seem to have a come a long and meandering way, travelling from the first sail in decades by John Kearney's Mavis in her new Maine home, to the skills of Larry Archer and others in putting vigorous new life into classic old boats here in Ireland. But the message is that the skills are available, the enthusiasm is there, and when the current pall over all our lives is lifted, the fleet will be there and ready to sail.

Not everyone gets the opportunity to restore a boat built by their grandfather, a gem of a boat whose construction started 70 years ago. But then, not everyone has had a professional seafaring and recreational sailing career to match that of Pat Murphy of Glenbrook on Cork Harbour. His working days at sea in his progression towards becoming a Master Mariner involved some very challenging contracts, while his varied sailing career has included many years at the sharp end of the International Dragon Class.

Slipping sweetly along, leaving scarcely any wake – this is classic sailing at its best. Photo: Robert Bateman

Slipping sweetly along, leaving scarcely any wake – this is classic sailing at its best. Photo: Robert Bateman

In fact, it's such a fascinating story that we'll be covering it in much greater detail in a proper feature when the evenings have closed in, and the main part of the sailing in this harshly-compressed season has been completed to provide more time and space. But for now, last Sunday provided the opportunity for Robert Bateman to capture some glorious "essence of summer" photos which will be a tonic for everyone during the current spell of decidedly mixed weather in this national mood of anxiety as we deal with the pandemic.

Pinkeen is an Alan Buchanan-designed 23ft Colleen Class, of which three were built for Kinsale in the 1950s, with one of them – Pinkeen for Knolly Stokes of the distinguished Cork city clock-making firm – being built in Kinsale itself by Pat's grandfather, senior boatbuilder John Thuillier. He started the work in 1950, when he was already having a busy year as he was also founding Commodore of Kinsale YC in 1950, but as he happened to be already 80 years old, the boatbuilding was at a quiet pace, and it was 1952 when he had her completed.

Happy man. Having had a maritime career which included some very challenging work in distant places, Pat Murphy is particularly appreciative of the pleasure of restoring and sailing the boat his grandfather built. Photo: Robert Bateman

Happy man. Having had a maritime career which included some very challenging work in distant places, Pat Murphy is particularly appreciative of the pleasure of restoring and sailing the boat his grandfather built. Photo: Robert Bateman

Over the 68 years since, Pinkeen has been here and there, including a stint in Galway. But Pat Murphy was always drawn to her, and when he bought her in 2005, she was back in Cork Harbour and definitely showing her age. He has done some of the restoration work himself and some heavier tasks have been undertaken on a piecemeal basis by professionals.

But in 2018 he got her to Jim Walsh in his international-standard classic boatbuilding and restoration workshops in Nohaval beside that hidden little inlet on the Cork coast between Crosshaven and Oysterhaven, and after Pinkeen had emerged, gleaming in sublime condition, all that was needed was this year's new suit of sails from UK Sailmakers of Crosshaven – also to recognised international classic practice in cream sailcloth – to make the project and the picture complete.

The result is a little boat which truly glows as she sails sweetly along, bringing joy to an exceptional owner-skipper, and great pleasure to the rest of us in a year when such special pleasures are trebly valuable.

"Leave no trace". The effortless way in which Pinkeen slips cleanly through the water is an example which can be usefully transferred to others areas of activity, while her sweetly-fitting classic-style sails from UK Sailmakers of Crosshaven demonstrate how important it is to get the complete look for the most satisfying and authentic overall result. Photo: Robert Bateman

"Leave no trace". The effortless way in which Pinkeen slips cleanly through the water is an example which can be usefully transferred to others areas of activity, while her sweetly-fitting classic-style sails from UK Sailmakers of Crosshaven demonstrate how important it is to get the complete look for the most satisfying and authentic overall result. Photo: Robert Bateman

The complete picture, with a recollection of times past. The elegant new sails from UK Crosshaven Sailmakers include the Colleen Class symbol first promoted in Kinsale in 1952. Photo: Barry Hayes

The complete picture, with a recollection of times past. The elegant new sails from UK Crosshaven Sailmakers include the Colleen Class symbol first promoted in Kinsale in 1952. Photo: Barry Hayes

In the current wave of revulsion against slavery and its appalling history, no European nation has totally clean hands. For although we might like to think that the huge Caribbean sugar plantations worked by African slaves in the 1800s brought tainted wealth mainly to cities such as Bristol, Liverpool, Glasgow and London in Great Britain, with Ireland largely uninvolved, when slavery itself was finally abolished in the British Empire in 1833 (the Slave Trade having been banned since 1807), all the slave owners were generously recompensed for the loss of their “property”, and a number of them proved to have Irish addresses.

Not that slavery was anything new in Ireland. It was an integral part of the ancient Gaelic economy and culture, and after the Vikings had taken over the little settlement of Baile Atha Cliath in the delta marshes of the River Liffey and turned it into the thriving port and trading hub of Dublin, it quickly reached the decidedly dubious peak around 1000AD of being Europe’s largest slave-trading centre. Captive Irish men and women were sold into a life of complete drudgery in every corner of the Viking Empire, which means that DNA tests can reveal the sometimes significant presence of Irish genes in some remarkably remote places where the longships once prowled.

The 100ft Viking ship Sea Stallion may symbolise the freedom of the seas for her rugged crew. But when the original was built in Dublin a thousand years ago of timber from Glendalough, its Norse rulers had made the port the largest slave-trading centre in their widespread empire, and possibly in the entire world

The 100ft Viking ship Sea Stallion may symbolise the freedom of the seas for her rugged crew. But when the original was built in Dublin a thousand years ago of timber from Glendalough, its Norse rulers had made the port the largest slave-trading centre in their widespread empire, and possibly in the entire world

But while the Dublin slave trading of a thousand years ago was on a then-epic scale, it was decidedly modest by comparison with the Transatlantic trade from West Africa from the 1500s onwards, which was started by the Portuguese, the Spaniards and the Dutch, but was then dominated the by the British and turned into people transport – in worse conditions than cattle - on an industrial scale involving millions of human beings.

The perverted ingenuity which went in making the slave ships both efficient and fast meant that the authorities faced an enormous challenge in trying to stamp out the trade after 1807, but once the slavery itself was officially abolished in 1833, those involved in eradicating it were encouraged by having a real chance of reducing the pernicious business. And what they needed more than anything else to continue eradication was fast and nimble warships, for the slaveships – the “blackbirders” - were masterpieces of twisted ingenuity in their superb all round performance and speed, and catching and arresting them required high-speed manoeuvrable sailing warships.

This is where the Earl of Belfast (1797-1883) and his 334-ton brig-rigged “yacht” Waterwitch of 1828 come into the story. Lord Belfast was the heir to the Marquess of Donegall, whose family the Chichesters had done well out of an ancestor, Arthur Chichester, Lord Deputy of Ireland from 1605 to 1615, whose international mercenary experience stood him to good stead in the war-making and conquest aspects of his new official position in Ireland.

In fact, Chichester (whose extended family from North Devon later included pioneer aviator and yacht voyager Francis Chichester) was too successful for his own good in taking over control of vast swatches of south Antrim and East Donegal and other areas, as well as playing a significant role - as the new landowner and charter-holder of Belfast - in turning it from a tiny lough-head village into the makings of a major port, and a commercial and industrial centre of eventually global significance.

Arthur Chichester was effectively the founder of Belfast, but though he was successful as a warlike land-grabber, he was not so good at land management, and his financial abilities were woeful

Arthur Chichester was effectively the founder of Belfast, but though he was successful as a warlike land-grabber, he was not so good at land management, and his financial abilities were woeful

For all was not as it seems. Because he’d acquired control over so much land, Chichester had to outsource most of its management to middlemen as he went on to handle other challenges at home and abroad where his military expertise flourished, and as a result, the family seem to have been almost constantly in financial difficulties.

But as was said of the banks and other large enterprises during the economic crash of 2008, the vast and rambling Chichester empire in Ulster was simply too large to fail, and though the land-grabbed rural tenantry in Country Antrim and Donegal, and the industrious rate-paying citizens of the rapidly-growing Belfast, will have had mixed feelings about their strictly-enforced payments pouring into what seemed at a times like a financial black hole, outwardly at least the Chichesters were flying, with Sir Arthur Chichester’s descendants on an upwards trajectory which reached its peak when the head of the family became the Marquess of Donegall, while his son and heir was the Earl of Belfast, their family’s rise and importance being underlined by the rapidly-growing Belfast including Chichester Street, Donegall Place, and Donegall Avenue in its expanding layout.

Yet while their outwards links to the city and other extensive properties in the north of Ireland appeared strong – including the 1830s Earl of Belfast being Westminster MP for Carrickfergus and Belfast and an important figure at the royal court in London - there were new links through marriage to County Wexford, where Dunbrody House (now Kevin Dundon’s renowned gastro-hotel) was to become a later Marquess of Donegall’s main residence, and indeed the family still live nearby.

The Earl of Belfast (1797-1883) was an exceptionally good judge of yacht and sail design, but his high level of enthusiasm for the sport didn’t help his perilous finances

The Earl of Belfast (1797-1883) was an exceptionally good judge of yacht and sail design, but his high level of enthusiasm for the sport didn’t help his perilous finances

But the Earl of Belfast of the 1820s and ’30s preferred if at all possible to spend his time in his house in Cowes when not on parliamentary or royal duties in London, for he was mad keen on sailing, an enthusiastic and active member of the recently-formed (1815) Royal Yacht Squadron, and his preferred personal company was with the leading local ship-builder Joseph Samuel White whose family firm had been founded way back in 1694 and continued to build boats yachts and ship until 1974, while the third member of this intriguing and innovative triumvirate was George Ratsey, an early light in the stellar formation which was to become the distinguished Ratsey family, who were noted also for boat-building talents, but became world-beaters in sail-making.

In the 1820s Lord Belfast’s two specialists created him a special racing yacht with the cutter Harriet, which was so successful that his Lordship announced that, having done all he could with fore-and-aft rig, he would in the 1830s turn his attention to square rig with the philanthropic intention of helping to improve the sailing qualities of the ships of the Royal Navy by competition and example.

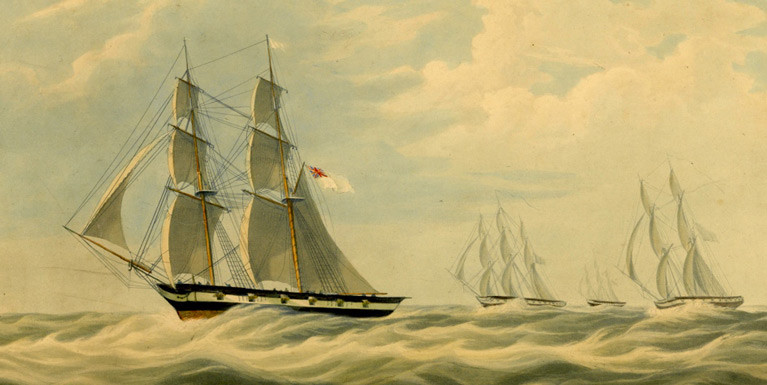

The racing cutter Harriet with which the Earl of Belfast first made his mark in the 1820s

The racing cutter Harriet with which the Earl of Belfast first made his mark in the 1820s

Joseph White built this 334-ton two-masted brig-rigged ship Waterwitch in Cowes in 1832, while George Ratsey set-to in his lofts nearby to create the finest racing sails money could buy, even if - in the case of the Earl of Belfast - it was all money which came very much under the “future earnings” category, with much of it resulting in time from the sweat off the backs of small farmers in Antrim and Donegal.

Although she had the outward look of a superyacht of the 1830s (had such a term then existed), the Earl of Belfast kept her sparsely fitted in basic navy style, and set about arranging a match against the best navy vessels. Yet the Royal Navy were oddly unenthusiastic about being publicly shown up by such a contest, for by now Lord Belfast had even given his brig a marked naval-style black-and-white stripe along where the gunports were located.

On every point of sailing, Wayerwotch out-performed the crack vessels of the Royal Navy’s Channel Squadron

On every point of sailing, Wayerwotch out-performed the crack vessels of the Royal Navy’s Channel Squadron

So eventually in exasperation, in 1834 and with the marine painter William John Huggins on hand to record the scene, he sailed the Waterwitch in close company on all points of sailing with the crack Royal Navy Channel Squadron as it made its regular parade of power and sea speed between Dover and the Isles of Scilly, and on every point of sailing and in all strengths of wind, Waterwitch was comfortably the top performer.

But despite a press clamour and public campaign, for a while, the naval authorities behaved as though it had never happened, so in exasperation, Lord Belfast spent more of other people’s money in making Waterwitch more of a yacht, and he won a hundred guineas of it back again after winning a close-fought challenge match race in early September 1834 to the Eddystone Lighthouse and back against the hottest big racing yacht of the day, the schooner Galatea.

It was this match challenge which finally seems to have spurred the Navy to action. The Earl of Belfast may have hoped that the Royal Navy would have been inspired to build their new ships as larger versions of Waterwitch, and to use George Ratsey more extensively as their sailmaker or at least a sailmaking consultant, and in this, he was partially successful. But in a sense, they side-stepped the issue by simply buying the Waterwitch, and almost immediately dispatching her to join the West Africa Squadron where she was seen as ideal for a slave-ship chasing role.

In the Hundred Guinea Match of September 1834, the schooner Galatea may have been first away, but Wayerwitch (left, and now modified back to yacht style) was to win

In the Hundred Guinea Match of September 1834, the schooner Galatea may have been first away, but Wayerwitch (left, and now modified back to yacht style) was to win

The flyer of Cowes was not even given the distinction of being made HMS – the navy men were rigid in their approach to this cheeky vessel which had so distinctly shown them up, and throughout her successful time with the Royal Navy she was always HMB – Her Majesty’s Brig Waterwitch.

In its latter days, the final elimination of the West African slave trade was possibly the most demanding phase of all, and until she was taken off the station in 1843, HMB Waterwitch played a key role in freeing more than 25,000 slaves. It was appalling work, as the fast little ship had to overcome the slavers and then put a delivery crew aboard the captured vessel to sail it to some port where the tragic cargo could be humanely dealt with.

The Squadron’s base was at the remote island of St Helena, and the placing of crews on slave ships often meant she returned to the island’s open roadstead with barely enough crew to handle the ship and further burdened with the knowledge that disease was so rife that they would see few enough of their shipmates again.

But in the tiny community on St Helena, they always received a warm and supportive welcome as the most successful slave-trader hunting ship of all, and a Vice-Admiralty Court on the island from 1840 until 1872 meant that those slave-running prisoners with whom they’d returned could be dealt with properly through internationally-recognised law.

So important was the St Helena link to Waterwitch’s crew that when her duties there were concluded, the impressive Waterwitch Memorial was erected in a pleasant spot on the island. Its inscription reads:

“This column was erected by the commander, officers and crew of Her Majesty’s Brig Waterwitch to the memory of their shipmates who died while serving on the coast of Africa AD 1835-1843. The greatest number died while absent on captured slave vessels. Their remains were either left in different parts of Africa or given to the sea, their graves alike undistinguished. This Island is selected for the record because three lies buried here and because the deceased, as well as their surviving comrades, ever met the warmest welcome from its inhabitants”.

The Earl of Belfast’s very special brig was to survive until 1861 when – tired by her exertion in hostile climates, and out-dated by the arrival of steam vessels - she was quietly broken up. As for his Lordship, he and his father the Marquess of Donegall ran out of road for a while in the 1840s, and they were jointly brought to bankruptcy for 400,000 pounds, which would be squillions today.

But all was not lost. Belfast – then still a town, though a rapidly growing one rising prosperity – was sold out from under them to pay their debts, ad that was one problem solved. Then the Wexford connection injected new resources, and on they went, with the Waterwitch Earl of Belfast – now the Marquess of Donegall – reported as having died in his beloved Cowes in 1883.

It’s a decidedly mixed story. Nevertheless, in the mood of the moment, is it inappropriate to suggest that this might be the time for a second Waterwitch Memorial, this time in Belfast City Hall?

The Waterwitch Memorial on St Helena recalls a special Belfast link to suppression of the international slave trade

The Waterwitch Memorial on St Helena recalls a special Belfast link to suppression of the international slave trade

This article was first published 7th July 2020