In the current wave of revulsion against slavery and its appalling history, no European nation has totally clean hands. For although we might like to think that the huge Caribbean sugar plantations worked by African slaves in the 1800s brought tainted wealth mainly to cities such as Bristol, Liverpool, Glasgow and London in Great Britain, with Ireland largely uninvolved, when slavery itself was finally abolished in the British Empire in 1833 (the Slave Trade having been banned since 1807), all the slave owners were generously recompensed for the loss of their “property”, and a number of them proved to have Irish addresses.

Not that slavery was anything new in Ireland. It was an integral part of the ancient Gaelic economy and culture, and after the Vikings had taken over the little settlement of Baile Atha Cliath in the delta marshes of the River Liffey and turned it into the thriving port and trading hub of Dublin, it quickly reached the decidedly dubious peak around 1000AD of being Europe’s largest slave-trading centre. Captive Irish men and women were sold into a life of complete drudgery in every corner of the Viking Empire, which means that DNA tests can reveal the sometimes significant presence of Irish genes in some remarkably remote places where the longships once prowled.

The 100ft Viking ship Sea Stallion may symbolise the freedom of the seas for her rugged crew. But when the original was built in Dublin a thousand years ago of timber from Glendalough, its Norse rulers had made the port the largest slave-trading centre in their widespread empire, and possibly in the entire world

The 100ft Viking ship Sea Stallion may symbolise the freedom of the seas for her rugged crew. But when the original was built in Dublin a thousand years ago of timber from Glendalough, its Norse rulers had made the port the largest slave-trading centre in their widespread empire, and possibly in the entire world

But while the Dublin slave trading of a thousand years ago was on a then-epic scale, it was decidedly modest by comparison with the Transatlantic trade from West Africa from the 1500s onwards, which was started by the Portuguese, the Spaniards and the Dutch, but was then dominated the by the British and turned into people transport – in worse conditions than cattle - on an industrial scale involving millions of human beings.

The perverted ingenuity which went in making the slave ships both efficient and fast meant that the authorities faced an enormous challenge in trying to stamp out the trade after 1807, but once the slavery itself was officially abolished in 1833, those involved in eradicating it were encouraged by having a real chance of reducing the pernicious business. And what they needed more than anything else to continue eradication was fast and nimble warships, for the slaveships – the “blackbirders” - were masterpieces of twisted ingenuity in their superb all round performance and speed, and catching and arresting them required high-speed manoeuvrable sailing warships.

This is where the Earl of Belfast (1797-1883) and his 334-ton brig-rigged “yacht” Waterwitch of 1828 come into the story. Lord Belfast was the heir to the Marquess of Donegall, whose family the Chichesters had done well out of an ancestor, Arthur Chichester, Lord Deputy of Ireland from 1605 to 1615, whose international mercenary experience stood him to good stead in the war-making and conquest aspects of his new official position in Ireland.

In fact, Chichester (whose extended family from North Devon later included pioneer aviator and yacht voyager Francis Chichester) was too successful for his own good in taking over control of vast swatches of south Antrim and East Donegal and other areas, as well as playing a significant role - as the new landowner and charter-holder of Belfast - in turning it from a tiny lough-head village into the makings of a major port, and a commercial and industrial centre of eventually global significance.

Arthur Chichester was effectively the founder of Belfast, but though he was successful as a warlike land-grabber, he was not so good at land management, and his financial abilities were woeful

Arthur Chichester was effectively the founder of Belfast, but though he was successful as a warlike land-grabber, he was not so good at land management, and his financial abilities were woeful

For all was not as it seems. Because he’d acquired control over so much land, Chichester had to outsource most of its management to middlemen as he went on to handle other challenges at home and abroad where his military expertise flourished, and as a result, the family seem to have been almost constantly in financial difficulties.

But as was said of the banks and other large enterprises during the economic crash of 2008, the vast and rambling Chichester empire in Ulster was simply too large to fail, and though the land-grabbed rural tenantry in Country Antrim and Donegal, and the industrious rate-paying citizens of the rapidly-growing Belfast, will have had mixed feelings about their strictly-enforced payments pouring into what seemed at a times like a financial black hole, outwardly at least the Chichesters were flying, with Sir Arthur Chichester’s descendants on an upwards trajectory which reached its peak when the head of the family became the Marquess of Donegall, while his son and heir was the Earl of Belfast, their family’s rise and importance being underlined by the rapidly-growing Belfast including Chichester Street, Donegall Place, and Donegall Avenue in its expanding layout.

Yet while their outwards links to the city and other extensive properties in the north of Ireland appeared strong – including the 1830s Earl of Belfast being Westminster MP for Carrickfergus and Belfast and an important figure at the royal court in London - there were new links through marriage to County Wexford, where Dunbrody House (now Kevin Dundon’s renowned gastro-hotel) was to become a later Marquess of Donegall’s main residence, and indeed the family still live nearby.

The Earl of Belfast (1797-1883) was an exceptionally good judge of yacht and sail design, but his high level of enthusiasm for the sport didn’t help his perilous finances

The Earl of Belfast (1797-1883) was an exceptionally good judge of yacht and sail design, but his high level of enthusiasm for the sport didn’t help his perilous finances

But the Earl of Belfast of the 1820s and ’30s preferred if at all possible to spend his time in his house in Cowes when not on parliamentary or royal duties in London, for he was mad keen on sailing, an enthusiastic and active member of the recently-formed (1815) Royal Yacht Squadron, and his preferred personal company was with the leading local ship-builder Joseph Samuel White whose family firm had been founded way back in 1694 and continued to build boats yachts and ship until 1974, while the third member of this intriguing and innovative triumvirate was George Ratsey, an early light in the stellar formation which was to become the distinguished Ratsey family, who were noted also for boat-building talents, but became world-beaters in sail-making.

In the 1820s Lord Belfast’s two specialists created him a special racing yacht with the cutter Harriet, which was so successful that his Lordship announced that, having done all he could with fore-and-aft rig, he would in the 1830s turn his attention to square rig with the philanthropic intention of helping to improve the sailing qualities of the ships of the Royal Navy by competition and example.

The racing cutter Harriet with which the Earl of Belfast first made his mark in the 1820s

The racing cutter Harriet with which the Earl of Belfast first made his mark in the 1820s

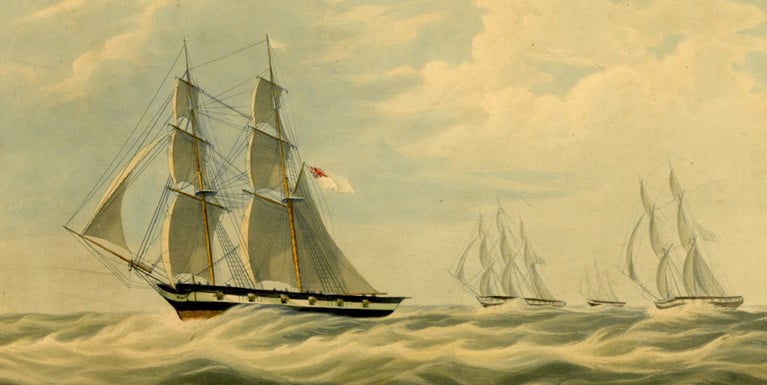

Joseph White built this 334-ton two-masted brig-rigged ship Waterwitch in Cowes in 1832, while George Ratsey set-to in his lofts nearby to create the finest racing sails money could buy, even if - in the case of the Earl of Belfast - it was all money which came very much under the “future earnings” category, with much of it resulting in time from the sweat off the backs of small farmers in Antrim and Donegal.

Although she had the outward look of a superyacht of the 1830s (had such a term then existed), the Earl of Belfast kept her sparsely fitted in basic navy style, and set about arranging a match against the best navy vessels. Yet the Royal Navy were oddly unenthusiastic about being publicly shown up by such a contest, for by now Lord Belfast had even given his brig a marked naval-style black-and-white stripe along where the gunports were located.

On every point of sailing, Wayerwotch out-performed the crack vessels of the Royal Navy’s Channel Squadron

On every point of sailing, Wayerwotch out-performed the crack vessels of the Royal Navy’s Channel Squadron

So eventually in exasperation, in 1834 and with the marine painter William John Huggins on hand to record the scene, he sailed the Waterwitch in close company on all points of sailing with the crack Royal Navy Channel Squadron as it made its regular parade of power and sea speed between Dover and the Isles of Scilly, and on every point of sailing and in all strengths of wind, Waterwitch was comfortably the top performer.

But despite a press clamour and public campaign, for a while, the naval authorities behaved as though it had never happened, so in exasperation, Lord Belfast spent more of other people’s money in making Waterwitch more of a yacht, and he won a hundred guineas of it back again after winning a close-fought challenge match race in early September 1834 to the Eddystone Lighthouse and back against the hottest big racing yacht of the day, the schooner Galatea.

It was this match challenge which finally seems to have spurred the Navy to action. The Earl of Belfast may have hoped that the Royal Navy would have been inspired to build their new ships as larger versions of Waterwitch, and to use George Ratsey more extensively as their sailmaker or at least a sailmaking consultant, and in this, he was partially successful. But in a sense, they side-stepped the issue by simply buying the Waterwitch, and almost immediately dispatching her to join the West Africa Squadron where she was seen as ideal for a slave-ship chasing role.

In the Hundred Guinea Match of September 1834, the schooner Galatea may have been first away, but Wayerwitch (left, and now modified back to yacht style) was to win

In the Hundred Guinea Match of September 1834, the schooner Galatea may have been first away, but Wayerwitch (left, and now modified back to yacht style) was to win

The flyer of Cowes was not even given the distinction of being made HMS – the navy men were rigid in their approach to this cheeky vessel which had so distinctly shown them up, and throughout her successful time with the Royal Navy she was always HMB – Her Majesty’s Brig Waterwitch.

In its latter days, the final elimination of the West African slave trade was possibly the most demanding phase of all, and until she was taken off the station in 1843, HMB Waterwitch played a key role in freeing more than 25,000 slaves. It was appalling work, as the fast little ship had to overcome the slavers and then put a delivery crew aboard the captured vessel to sail it to some port where the tragic cargo could be humanely dealt with.

The Squadron’s base was at the remote island of St Helena, and the placing of crews on slave ships often meant she returned to the island’s open roadstead with barely enough crew to handle the ship and further burdened with the knowledge that disease was so rife that they would see few enough of their shipmates again.

But in the tiny community on St Helena, they always received a warm and supportive welcome as the most successful slave-trader hunting ship of all, and a Vice-Admiralty Court on the island from 1840 until 1872 meant that those slave-running prisoners with whom they’d returned could be dealt with properly through internationally-recognised law.

So important was the St Helena link to Waterwitch’s crew that when her duties there were concluded, the impressive Waterwitch Memorial was erected in a pleasant spot on the island. Its inscription reads:

“This column was erected by the commander, officers and crew of Her Majesty’s Brig Waterwitch to the memory of their shipmates who died while serving on the coast of Africa AD 1835-1843. The greatest number died while absent on captured slave vessels. Their remains were either left in different parts of Africa or given to the sea, their graves alike undistinguished. This Island is selected for the record because three lies buried here and because the deceased, as well as their surviving comrades, ever met the warmest welcome from its inhabitants”.

The Earl of Belfast’s very special brig was to survive until 1861 when – tired by her exertion in hostile climates, and out-dated by the arrival of steam vessels - she was quietly broken up. As for his Lordship, he and his father the Marquess of Donegall ran out of road for a while in the 1840s, and they were jointly brought to bankruptcy for 400,000 pounds, which would be squillions today.

But all was not lost. Belfast – then still a town, though a rapidly growing one rising prosperity – was sold out from under them to pay their debts, ad that was one problem solved. Then the Wexford connection injected new resources, and on they went, with the Waterwitch Earl of Belfast – now the Marquess of Donegall – reported as having died in his beloved Cowes in 1883.

It’s a decidedly mixed story. Nevertheless, in the mood of the moment, is it inappropriate to suggest that this might be the time for a second Waterwitch Memorial, this time in Belfast City Hall?

The Waterwitch Memorial on St Helena recalls a special Belfast link to suppression of the international slave trade

The Waterwitch Memorial on St Helena recalls a special Belfast link to suppression of the international slave trade

This article was first published 7th July 2020