Displaying items by tag: Ilen

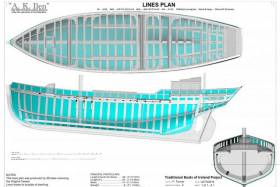

Dublin Bay 21 Revival & Ilen Restoration Get On-Site Consultation With Classics Designer Paul Spooner

The restoration of classic yachts and traditional craft to the recognised international standard is still relatively new in Ireland writes W M Nixon. In fact, it could be argued that the major project in Dunmore East, completed in 2005 on the 1894 G L Watson-designed 37ft cutter Peggy Bawn, is still the only example we have in Ireland of the painstaking and meticulous research and work of the highest quality that is required on a vessel of this size for total authenticity.

The Peggy Bawn project was for maritime historian Hal Sisk, and while Michael Kennedy was the lead shipwright, many specialist talents were involved in creating a widely-admired masterpiece.

Hal Sisk aboard the restored 1894 Peggy Bawn in Dublin Bay in 2005. In the background is the Jeanie Johnston – in those days, she still sailed. Photo: W M Nixon

Hal Sisk aboard the restored 1894 Peggy Bawn in Dublin Bay in 2005. In the background is the Jeanie Johnston – in those days, she still sailed. Photo: W M Nixon

Now Hal Sisk is working on a completely different idea, a revival of the legendary Dublin Bay 21 class, the famous Mylne design of 1902-03. But in this case, far from bringing the original and almost-mythical gaff cutter rig with jackyard topsail back to life above a traditionally-constructed hull, he is content to have an attractive gunter-rigged sloop – “American gaff” some would call it – above a new laminated cold-moulded hull which is being built inverted but will, when finished and upright, be fitted on the original ballast keels, thereby maintaining the boat’s continuity of existence, the presence of the true spirit of the ship..

It’s a fascinating and complex project to which we’ll be returning in future postings on Afloat.ie. For now, the first DB 21 to get this treatment is Naneen, originally built in 1905 by Clancy of Dun Laoghaire for T. Cosby Burrowes, a serial boat owner from Cavan who had formerly owned Nance, the 1899 Dublin Bay 25 which was the only DB25 to be built by designer William Fife’s own yard in Fairlie – she still sails in the Mediterranean, now under the name of Iona.

As for Naneen, she was soon under new ownership as Burrowes interests turned elsewhere. She raced with the class in Dublin Bay under the original gaff rig until 1964, and then under the masthead Bermudan sloop rig, which kept these attractive boats going as an active racing class until August 1986.

In that fateful year, the after-effects of Hurricane Charlie in Dun Laoghaire Harbour resulted in their damaged hulls of the Dublin Bay 21s being retrieved and stored in a Wicklow farmyard while everyone worked out various schemes to make good use of this historic flotilla of seven very significant and attractive boats.

Hal Sisk and DB21 “Guardian” Fionan de Barra, after much research, have now developed this moulded hull/simpler rig philosophy which revives the class while retaining its character. And in Steve Morris at Kilrush in County Clare, they have a skilled boat-builder who has already shown with the Shannon cutter Sally O’Keeffe and other projects that he brings very special talents that work well in a wide variety of boat-building challenges.

The proposed rig for the new-style Dublin Bay 21s will be a variation on this rig which Alfred Mylne designed for the DB21 sistership Zanetta, which was built in Scotland for a Clyde owner in 1918, but was used as a cruiser and never joined her sister-ships in Dublin Bay

The proposed rig for the new-style Dublin Bay 21s will be a variation on this rig which Alfred Mylne designed for the DB21 sistership Zanetta, which was built in Scotland for a Clyde owner in 1918, but was used as a cruiser and never joined her sister-ships in Dublin Bay

However, in order to maintain the integrity of the project, the actual design of the Dublin Bay 21 hull had to be agreed to very close limits, far removed from the free-and-easy approach of boat-builders in the early 1900s. For this, they have been able to draw on the highly-trained skills of designer and classics consultant Paul Spooner, who worked with Duncan Walker’s famous Fairlie Restorations company for twenty years, and has seen through some extremely demanding projects thanks to his fully-qualified status as a naval architect and engineer.

Using Paul Spooner’s drawings, the work in Kilrush has been proceeding steadily since late summer, and in recent days a stage had been reached where Paul Spooner’s presence was required on-site in order to finalise some key decisions. But he’s a very busy man, so to optimize his presence here, Hal Sisk linked-up with Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Project of Limerick and Baltimore, as the riggers developing the restored sail-plan of the 1926-built 56ft Conor O’Brien ketch Ilen had also been seeking Paul’s expert advice on their work.

While logistically challenging, it was all just possible in three recent days, and despite freezing damp weather in the west, Paul Spooner put in useful time in Kilrush where Steve Morris’s work is a joy to behold, and then he was transferred to the care of the Ilen team and whisked from Limerick to Baltimore.

Paul Spooner (top right) with some of the Ilen team aboard the ship in Baltimore with the restored wheel steering system. With him are (top left) Jim McInerney and James Madigan (wooden boat builder), on wheel is Tony Daly (Shannon fisherman & wooden boatbuilder), while right foreground is Matt Dirr (“Builder of Curved Structures”). Photo: Gary MacMahon

Paul Spooner (top right) with some of the Ilen team aboard the ship in Baltimore with the restored wheel steering system. With him are (top left) Jim McInerney and James Madigan (wooden boat builder), on wheel is Tony Daly (Shannon fisherman & wooden boatbuilder), while right foreground is Matt Dirr (“Builder of Curved Structures”). Photo: Gary MacMahon

There, in The Old Corn Store in Oldcourt Boatyard where Ilen has been re-born, many assembled parts that we’ve seen recently on Afloat.ie being built in the Ilen Boat-Building School in Limerick has now been fitted in the ship, and here too the Paul Spooner presence brought reassurance that they were working in the right direction.

As for which direction Paul Spooner himself was going, it would have been overly-demanding for any lesser man. But having given advice of gold dust quality to two major restoration projects in Ireland, he then hopped on a plane in Dublin Airport and went to Japan, where he is being consulted on the restoration of a large 1927-vintage Camper & Nicholson ketch. That’s how it is at the leading edge of classic restoration projects.

Dream on…..Ilen School’s Matt Dirr in thoughtful mood aboard Ilen after the new Limerick-built footwell has been installed on board in Baltimore. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Dream on…..Ilen School’s Matt Dirr in thoughtful mood aboard Ilen after the new Limerick-built footwell has been installed on board in Baltimore. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Conor O’Brien Ketch Ilen Re-uses Old Gaelic Stadium Teak

The process of restoring the 1926-built 56ft Conor O’Brien ketch Ilen in Limerick and Baltimore has seen a countrywide network developing, a network in which anyone with access to redundant classic quality timber has been happy to see it finding a new use in the Ilen Boatbuilding School’s very special project writes W M Nixon.

Afloat.ie recently carried the story of how traditional rigging dead-eyes had been crafted from that rare timber lignum vitae, which in this case had been sourced from a former shipyard in Cork.

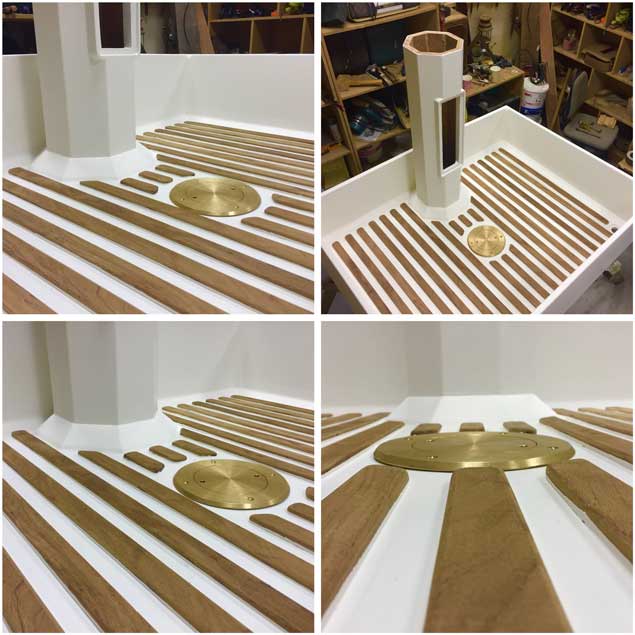

Now there has been a useful re-direction from nearer home, with teak which had provided slats for the seating in the old Markets Field Gaelic Stadium in Limerick for more than a century finding a new life as slats on the sole of the Ilen helmsman’s footwell.

Less is more. A little bit of teak, tastefully installed as slats on the sole of Ilen’s beautifully-completed new footwell, sets the Antique White finish off to perfection. Photos: Gary MacMahon

Less is more. A little bit of teak, tastefully installed as slats on the sole of Ilen’s beautifully-completed new footwell, sets the Antique White finish off to perfection. Photos: Gary MacMahon

A hundred and more years ago, teak – the king of timbers - was much more readily available than it is today, and was sometimes used to excess. But modern boat-builders have learned that with the scarcity of this lovely wood, less can be more, and the way that the relatively small amount of teak has been usefully installed in the beautifully finished Ilen footwell certainly bears this out.

Having made a couple of journeys between the Ilen herself in Oldcourt near Baltimore and the boat-building school in Limerick, the elegant footwell will finally be fully installed on the ship within the next week.

Conor O’Brien Ketch Ilen Starts to Feel Like a Living Ship Again

The process of transforming the restored hull and deck of the 1926-built 56ft Conor O’Brien historic ketch Ilen into a living ship continues writes W M Nixon. The programme is co-ordinated and combined between the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick, where they’re busy on the benches making or re-conditioning many items of gear and equipment, and in and around the ship herself with Liam Hegarty in Baltimore in West Cork. There, it finally all comes together, and last weekend provided a real sense of a new stage reached in the project.

James Madigan in the Ilen School in Limerick with a workshop-mockup of the traditional steering arrangement, including the helmsman’s footwell which has since been fitted in the ship. Photo: Gary McMahon

James Madigan in the Ilen School in Limerick with a workshop-mockup of the traditional steering arrangement, including the helmsman’s footwell which has since been fitted in the ship. Photo: Gary McMahon

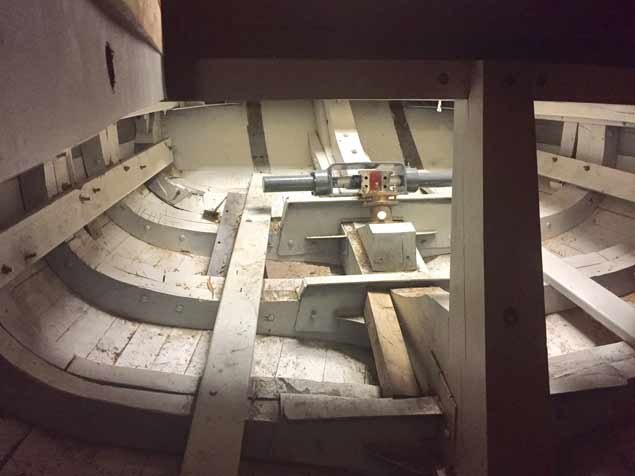

In Oldcourt, the hydraulic steering actuator – renovated in Limerick – is ready for final fitting to the rudder stock. Photo: Gary McMahon

In Oldcourt, the hydraulic steering actuator – renovated in Limerick – is ready for final fitting to the rudder stock. Photo: Gary McMahon

Lights gleamed from below where the accommodation is being created, and traditional timberwork shone with warmth in the homely setting of The Old Cornstore on the banks of the Ilen River. This much-loved waterway runs from Skibbereen down towards Baltimore to provide the home training waters of some of Ireland’s greatest contemporary rowers, as well as a sheltered setting for the always-fascinating boatyard complex.

The unique atmosphere of this special boat-building location is more cherished than ever. It had been feared that the Old Cornstore and the surrounding Oldcourt Boatyard were right in the path of serious damage from Storm Ophelia three weeks ago. But although a gust of 191 km/h was recorded out at the Fastnet Rock, and 135 km/h was logged at Sherkin Island just across from Baltimore, Oldcourt came through relatively unscathed. The place leads a charmed life.

Starting to look like a ship again. Snug under the Ophelia-surviving vintage roof in the Old Cornstore at Oldcourt, Ilen is now giving a much better impression of what she’ll be like to be aboard at sea. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Starting to look like a ship again. Snug under the Ophelia-surviving vintage roof in the Old Cornstore at Oldcourt, Ilen is now giving a much better impression of what she’ll be like to be aboard at sea. Photo: Gary MacMahon

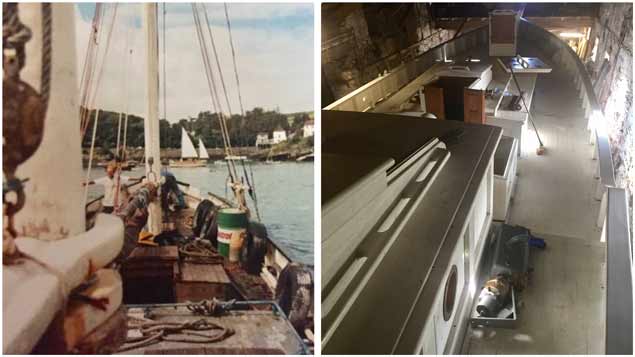

As for the ketch’s restoration project, a stage had been reached where teams from both Ilen Boatbuilding centres could usefully combine forces last Saturday to clear up the boat from end to end the better to appreciate what has been achieved, and to appraise what still needs to be done. In comparing the photos below which show Ilen as she was when last in commission at the Glandore Classics of 1998, and as she was on Saturday, there’s no doubting that the spirit of the old ship is being re-born.

Aboard Ilen as she was in 1998 at Glandore (left) and on deck last Saturday in Oldcourt (right). Photo: Gary MacMahon

Aboard Ilen as she was in 1998 at Glandore (left) and on deck last Saturday in Oldcourt (right). Photo: Gary MacMahon

As is the way with restorations, it’s intriguing to learn how various specialist items of equipment have been retrieved or saved. In a city with a metal-working tradition like Limerick, there’s an instinctive appreciation of the quality of the workmanship which has gone into the rigging hardware for shrouds and masts alike.

Some of Ilen’s rigging hardware, in a time-honoured style much-appreciated in a city with a metal-working tradition. Photo: Gary McMahon

Some of Ilen’s rigging hardware, in a time-honoured style much-appreciated in a city with a metal-working tradition. Photo: Gary McMahon

And although we’ve shown photos of the Ilen dead-eyes made from lignum vitae before, there’s something so fascinating about this densest of timbers (in this case “contributed from a former shipyard in Cork”) that a second or third look is surely justified, appreciating them as works of art shaped in the Ilen school in Limerick by Matt Dirr.

Matt Dirr crafting dead-eyes in the Ilen School. Photo: Gary McMahon Photo: Gary MacMahon

Matt Dirr crafting dead-eyes in the Ilen School. Photo: Gary McMahon Photo: Gary MacMahon

Dead-eyes finished and varnished. There is an eternal fascination in lignum vitae, the “wood of life”, one of the densest timbers in the world. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Dead-eyes finished and varnished. There is an eternal fascination in lignum vitae, the “wood of life”, one of the densest timbers in the world. Photo: Gary MacMahon

As for that rather choice bronze fairlead, we immediately fired back an enquiry to Ilen School Director Gary McMahon as to who made it, for it too is a work of art. The answer is he doesn’t know who made it, but having worked in metal himself he has long been an inveterate collector of special items which would otherwise be on their way to the scrapyard, and this came off an old vessel which was being dismantled in Limerick. Now, thanks to the Ilen Project, it will once again sail the seas.

A proper little work of art – a bronze fairlead, salvaged from a breaker’s yard many years ago. Photo: Gary MacMahon

A proper little work of art – a bronze fairlead, salvaged from a breaker’s yard many years ago. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Unlike the fairlead, this deck eyebolt is new-made, but it wouldn’t look out of place as a piece of functional art on a modern gallery. Photo: W M Nixon

Unlike the fairlead, this deck eyebolt is new-made, but it wouldn’t look out of place as a piece of functional art on a modern gallery. Photo: W M Nixon

Historic Ketch Ilen’s Busy Workshop in Limerick Keeps the Baltimore Show on the Road

Many people have dropped by the Old Cornstore on the riverside at Oldcourt in West Cork to see work progressing on the restoration of the 1926 Conor O’Brien ketch Ilen writes WM Nixon. And naturally they’ll have the impression that they’re at the main scene of the action. After all, the 56ft vessel certainly looks the part - a complete ship, full of promise in her distinctive new colour scheme.

But as Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick points out, even with a hefty traditional vessel like Ilen, the finished hull with deck in place is only about 35% of the complete and fully commissioned vessel. And though the assembly of the various parts inevitably has to take place in Oldcourt with Liam Hegarty and his team, much of what you’re looking at on the Ilen today was actually built in the Ilen School’s efficient workshops in Limerick city.

The Ilen herself in Oldcourt near Baltimore, newly painted and looking very well. Photo Ilen BS

The Ilen herself in Oldcourt near Baltimore, newly painted and looking very well. Photo Ilen BS

The new deckhouses, hatches etc on the Ilen were all made in Limerick. Photo Ilen BS

The new deckhouses, hatches etc on the Ilen were all made in Limerick. Photo Ilen BS

There, young people – indeed, people of all ages and from many backgrounds – are finding that working with wood, and creating parts for boats or building complete boats, is a profoundly interesting and fulfilling experience. In recent years, the Ilen School has turned out impressively authentic versions of the traditional Shannon gandelow, and in a completely different direction, sailing dinghies of the distinctive CityOne class to a very special design by the late Theo Rye.

One of the Ilen Boatbuilding School’s traditional gandelows on the Shannon in Limerick, heading upriver towards King John’s Castle. Photo: Gary MacMahon

One of the Ilen Boatbuilding School’s traditional gandelows on the Shannon in Limerick, heading upriver towards King John’s Castle. Photo: Gary MacMahon

It makes a change from the Shannon Estuary - the Ilen Boatbuilding School’s gandelows in Venice. Photos: Gary MacMahon

It makes a change from the Shannon Estuary - the Ilen Boatbuilding School’s gandelows in Venice. Photos: Gary MacMahon

These smaller craft have been imaginatively used by those who built them for various expeditions to events such as the Baltimore Woodenboat Festival and the Glandore Classics Regatta. And in 2014, the Gandelows somehow managed a remarkable double by taking part in the Thousandth Anniversary re-enactment of the Battle of Clontarf (wasn’t Brian Boru a Limerick man, after all?) and yet somehow also took in a Marine Festival in Venice, as it’s reckoned that the word “gandelow” originated from gondola, but mutated along the way.

Having taken such things and various other projects in their stride, the Ilen people in Limerick have enthusiastically lined up to build the deckhouses, hatchways, skylights, lignum vitae rigging deadeyes and many other items for Ilen herself. Each is an exquisite bit of marine joinerywork in its own right, and when fitted on the ship, they go so well with the overall concept that you’d be hard-pressed to guess that they were built many miles away, in the characterful city on Shannonside, rather than among the rolling green hills and woodland of West Cork.

Deadeyes made in Limerick from rare lignum vitae – the word is that this very high density wood “was sourced from a former shipyard in Cork”. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Deadeyes made in Limerick from rare lignum vitae – the word is that this very high density wood “was sourced from a former shipyard in Cork”. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Group discussion in Limerick with Liam, Trevor, Pete and Robert to sort and assess items of rigging gear. Photos: Gary MacMahon

Group discussion in Limerick with Liam, Trevor, Pete and Robert to sort and assess items of rigging gear. Photos: Gary MacMahon

Modern safety requirements dictate that the original guard-rail stanchions (left) have to be replaced by longer ones (right) to provide one metre clearance. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Modern safety requirements dictate that the original guard-rail stanchions (left) have to be replaced by longer ones (right) to provide one metre clearance. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The hydraulic steering actuator is cleaned and serviced before being sent for pressure testing. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The hydraulic steering actuator is cleaned and serviced before being sent for pressure testing. Photo: Gary MacMahon

But such is the case, because for all his fondness for West Cork, Conor O’Brien’s spirit is in Foynes Island on the Shannon Estuary, and Limerick is his city, the city of the O’Briens since time immemorial. And recently, Limerick has been turning out the stanchions for the Ilen’s guard-rails, something which is well in line with the city’s engineering traditions. But most impressive of all is the final work on finishing the spars.

When Ilen was shipped back from the Falklands in 1998, some of her surviving spars were in a decidedly poor conditions. But the new Limerick-built replacements are robust works of art, with a natural functional beauty. It really will be a show on the road, and then some, when they’re taken on that winding journey from Limerick down to Baltimore.

An authentic marine bronze Kobelt heavy duty engine control is sourced “by good fortune” – it cleans up a treat

An authentic marine bronze Kobelt heavy duty engine control is sourced “by good fortune” – it cleans up a treat

Finally getting there – Liam O’Donoghue gives Ilen’s new mainmast its finishing coats of paint – the special colour is “US Navy buff” Photo: Gary MacMahon

Finally getting there – Liam O’Donoghue gives Ilen’s new mainmast its finishing coats of paint – the special colour is “US Navy buff” Photo: Gary MacMahon

Restored Ketch Ilen Reaches the 'Watch This Space' Stage

With the hull of the 56ft 1926-built ketch Ilen fully restored in Oldcourt near Baltimore, attention has been turning to detailed items of equipment such as the steering system and the stern gear writes W M Nixon. And the “offering up” of the athwartships cathead, which will support the net under the mighty bowsprit as well as other more traditional functions such as lifting the anchor, has continued the migration of shaped wooden parts from the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick to Liam Hegarty and his shipwrights with the hull in West Cork.

Ilen’s new cathead (left), and the original one (right) from 1926. The simplification of the design to make do with one spar, instead of the traditional two at an angle, might have been Conor O’Brien’s own idea. Photo (left) Gary MacMahon

Ilen’s new cathead (left), and the original one (right) from 1926. The simplification of the design to make do with one spar, instead of the traditional two at an angle, might have been Conor O’Brien’s own idea. Photo (left) Gary MacMahon

The new cathead is athwartships, forward of the jaunty little foredeck hatch which originally provided access to the cramped crew accommodation in the eyes of the ship. Photo Gary MacMahon

The new cathead is athwartships, forward of the jaunty little foredeck hatch which originally provided access to the cramped crew accommodation in the eyes of the ship. Photo Gary MacMahon

As the historic photo taken from aloft of Ilen’s foredeck in her original form shows, the simplified cathead was one athwartships spar, whereas in larger vessels it could be two spars, one each side, and angled at about 45 degrees to the fore-and-aft line. In Ilen’s case, it was long enough to help in the business of keeping the bowsprit in place, while maximizing the amount of clear space on the foredeck and over the rail.

Overall, attention is now also well focused on working out a friendly layout in the capacious accommodation. Originally, in her days as the freight vessel in the Falkland Islands, the best part of Ilen’s roomy hull amidships was taken up with the cargo hold. The crew quarters were cramped places, either right forward, or crowded in down aft at the little deckhouse.

The steering system is introduced to the ship for the first time. Photo Gary MacMahon

The steering system is introduced to the ship for the first time. Photo Gary MacMahon

All the hull fittings are in the best marine bronze. Photo: Gary MacMahon

All the hull fittings are in the best marine bronze. Photo: Gary MacMahon

But with the restoration, the deckhouse is enhanced, and though a classic hatchway has been installed right forward, the team have to take decisions on how best to lay out the amidships below-deck area for a vessel which will have to fill several roles

When fully commissioned again, Ilen will be based in Limerick with her programme built around the Shannon Estuary and further afield. But the plan is to have only seven sleeping bunks rather than the twelve which might be possible if she were going to be used only as a sail training vessel.

While the Ilen project may be all about the restoration of a very traditional vessel, doubtless a non-traditional computer will be used to envisage the best possible use of all that lovely space below. And even when CAD facilities have been utilised, the best plan is to make a mock-up before finalising the details, for even the smallest modification of one part of the layout affects the way that everything else falls into place in a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle.

It’s worth persevering, for a traditionally-styled yet ergonomically friendly and welcoming layout below would make Ilen the little ship that everyone wants to be aboard.

An interesting amount of space to be filled. James Madigan of the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick down at Oldcourt in what used to be Ilen’s cargo hold, while behind him is the massive strengthening in the way of the mainmast. And on the left is ship’s dog Luna…… Photo: Gary MacMahon

An interesting amount of space to be filled. James Madigan of the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick down at Oldcourt in what used to be Ilen’s cargo hold, while behind him is the massive strengthening in the way of the mainmast. And on the left is ship’s dog Luna…… Photo: Gary MacMahon

Historic Ketch Ilen’s Restoration Moves on From Broad Strokes to Detail Work

With the hull of the 56ft 1926-built Conor O’Brien ketch Ilen now restored and painted in the building shed in Oldcourt near Baltimore, attention shifts increasingly to the long list of detail work that is needed to complete the project writes W M Nixon.

Much of this is ideally suited to the facilities available in the Ilen Boat Building School in Limerick, where director Gary MacMahon and his team have assembled a group of all the talents for teaching and learning. These days, the evocative aromas and sounds of traditional ship-building and its associated tasks permeate both the school in the city, and the building shed beside the Ilen River.

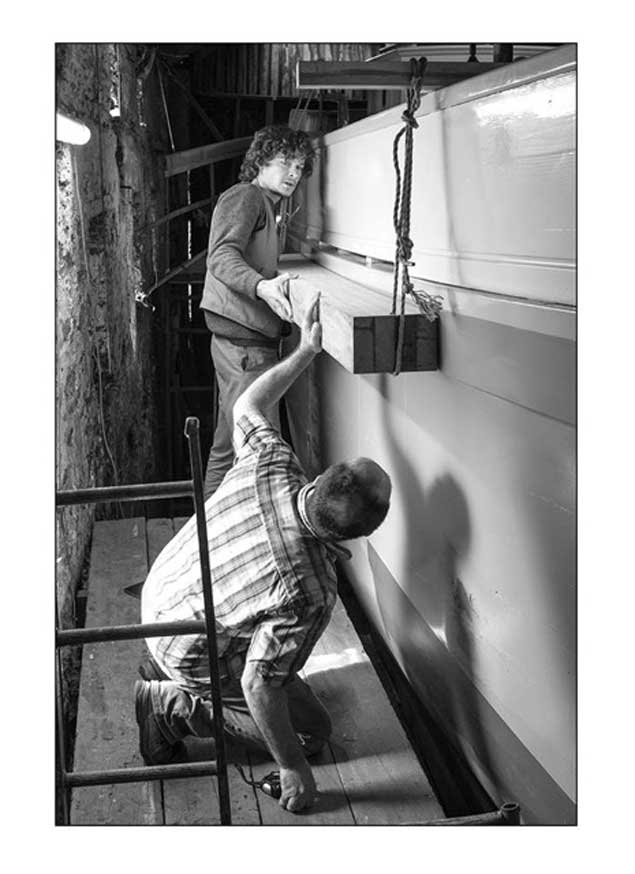

In the Old Cornstore on the River Ilen near Baltimore, Matt Dirr works towards a perfect fit for the classic chainplates (above and below). Photos: Kevin O’Farrell

In the Old Cornstore on the River Ilen near Baltimore, Matt Dirr works towards a perfect fit for the classic chainplates (above and below). Photos: Kevin O’Farrell

Conor O’Brien’s global circumnavigation in the 42ft ketch Saoirse in 1923-25 inspired the Falkland Islanders to ask for a larger sister-ship to the same concept for their inter-island communications vessel, and the resulting Ilen was able - among other things - to transfer up to 200 sheep on the inter-island channels.

In Limerick, James Madigan shapes a new Douglas Fir cathead Photo: Gary MacMahon

In Limerick, James Madigan shapes a new Douglas Fir cathead Photo: Gary MacMahon

With her larger size, she also enabled O’Brien and master shipwright Tom Moynihan of Baltimore to give more space to the steering gear. As O’Brien later admitted, they’d tried to pack so much into Saoirse’s compact 42ft hull that her steering wheel was awkwardly placed for long spells at the helm, so in Ilen they made a point of installing a more substantial arrangement which can now be seen re-created in Limerick.

In both the school in the city and the Old Cornstore in Oldcourt, it’s an immersive maritime experience of being transported back in time to the 1920s and far beyond.

Four angles on the re-created steering gear Photo; Gary McMahon

Four angles on the re-created steering gear Photo; Gary McMahon Molly MacMahon with the new steering wheel. In his subsequent books about seagoing gear and equipment, Conor O’Brien stipulated that the ideal size for a steering wheel is 42 inches. This is a “thin” 42 inches – as big as can be fitted. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Molly MacMahon with the new steering wheel. In his subsequent books about seagoing gear and equipment, Conor O’Brien stipulated that the ideal size for a steering wheel is 42 inches. This is a “thin” 42 inches – as big as can be fitted. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Traditional Ketch Ilen’s Chainplates Are Key to the Power of Her Rig

These days, it’s reckoned that chainplates – those vital fittings that attach a sailing boat’s standing rigging to her hull – should be wellnigh invisible writes W M Nixon. Indeed, when you look at some of the latest products of the French marine industry such as Paul O’Higgins’ 2017 Dun Laoghaire-Dingle Race winner, the JPK 10.80 Rockabill VI, the chainplates looks to be so small that you wonder if there isn’t some large hidden structure within to carry the real load.

Modern chainplates – as seen here on Paul O’Higgins’ JPK 10 80 Rockabill VI – tend to be minimalist. Photo Afloat.ie

Modern chainplates – as seen here on Paul O’Higgins’ JPK 10 80 Rockabill VI – tend to be minimalist. Photo Afloat.ie

But modern boat-building in carbon and composites has become so clever and weight-conscious that everything in a new boat is doing at least three things at once. Innovative designers find ways of carrying the loads on sections which also serve as part of the accommodation layout, while hiding the fundamental nature of the real work being done.

The total Ilen collection, traditionally galvanized. They may look identical, but they’re not. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The total Ilen collection, traditionally galvanized. They may look identical, but they’re not. Photo: Gary MacMahon

They started with the two starboard mizzen chainplates – and it took most of a day before they reckoned they were on the right track. Photo: Gary MacMahon

They started with the two starboard mizzen chainplates – and it took most of a day before they reckoned they were on the right track. Photo: Gary MacMahon

However, when the 56ft ketch Ilen was being built by Tom Moynihan and his shipwrights in Baltimore back in 1926, the function of the simple wrought steel chainplates was to transfer the load as visibly as possible over a significant section of the hull, with the chainplates uncompromisingly attached externally to minimise the chance of leaks.

Yacht builders naturally inclined to have their chainplates fitted internally, as that looked so much neater. But Ilen was of a traditional no-nonsense concept, and far from making the chainplates something to be invisible, the blacksmith of Baltimore crafted them to be simple and highly visible works of art.

Ilen serenely in waiting as her starboard mainmast chainplates are fitted. Photo: Michael Boyd

Ilen serenely in waiting as her starboard mainmast chainplates are fitted. Photo: Michael Boyd

It may look peaceful in the Old Cornstore, but you have only one chance to get this job right. Photo: Michael Boyd

It may look peaceful in the Old Cornstore, but you have only one chance to get this job right. Photo: Michael Boyd

Yet their seeming simplicity is itself a blind. The chainplates come up over timber channels which guide their load-carrying section clear – though only just – of the bulwarks. It all has to be worked to a very fine tolerance, as Liam Hegarty and his team discovered in recent days in the Old Cornstore at Oldcourt where Ilen’s restoration is shaping up, and the new chainplates – made this time round by specialist Colin Frake – have been fitted in a painstaking process.

Definitely not a job to be rushed. You get only one chance of marrying the chainplates, channels and hull to perfection.

Still work in progress. The channels may need a bit of further shaping before that lower curve is properly supported. Photo: James Madigan

Still work in progress. The channels may need a bit of further shaping before that lower curve is properly supported. Photo: James Madigan Once they’re finally fitted, the condition of the new chainplates can be regularly assessed. Note how the line of the upper part carries the rigging just clear of the bulwarks. Photo: James Madigan

Once they’re finally fitted, the condition of the new chainplates can be regularly assessed. Note how the line of the upper part carries the rigging just clear of the bulwarks. Photo: James Madigan

Restored Historic Ketch Ilen Starts to Get Authentic Rigging Through In-House Production

When the restoration project on the 1926-built 56ft Conor O’Brien/Tom Moynihan Falkland Islands Trading Ketch got under way at two locations – Liam Hegarty’s boat-building shed in the former Cornstore at Oldcourt near Baltimore, and the Ilen Boat-building School premises in Limerick – it was expected that final jobs such as making up the rigging and creating the sails would be contracted out to specialists writes W M Nixon.

But while the plan is still in place to have the sails made in traditional style by specialist sailmakers, Gary MacMahon and his team in the Ilen Boat-building School came to the realisation that they’d made so many international contacts over the years while the restoration has been under way that, if they could just get the right people’s schedules to harmonise, then they could learn how to make up the rigging in their own workshops as part of the broader training programme.

Conor O’Brien in 1926, when he delivered Ilen to the Falklands. He had received the order for the new ketch as a result of his visit to the Falkland Islands during his round the world voyage with the 42ft ketch Saoirse in 1923-25

Conor O’Brien in 1926, when he delivered Ilen to the Falklands. He had received the order for the new ketch as a result of his visit to the Falkland Islands during his round the world voyage with the 42ft ketch Saoirse in 1923-25

As a result, the Ilen Boat-building School became a hive of activity over the Bank Holiday Weekend and beyond, for that was the only time when noted heavy rigging experts Trevor Ross, who is originally from New Zealand, and Captain Piers Alvarez, master of the 45-metre barque-rigged tall ship Kaskelot, were both available to make their voluntary instructional contributions to the project.

Trevor Ross with a new eye splice in the Ilen Boat-building School in Limerick. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Trevor Ross with a new eye splice in the Ilen Boat-building School in Limerick. Photo: Gary MacMahon

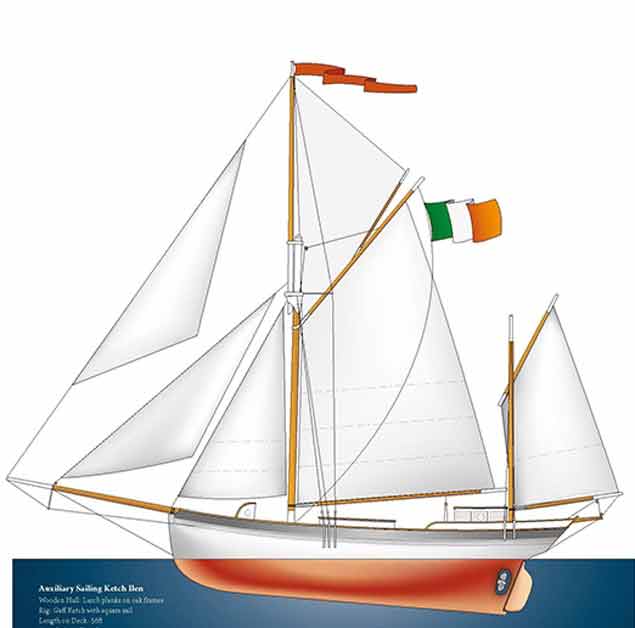

The re-creation of Ilen’s rig, as developed by Trevor Ross with the late Theo Rye

The re-creation of Ilen’s rig, as developed by Trevor Ross with the late Theo Rye

Trevor Ross was professionally at sea for ten years, during which time he became fascinated with traditional rigging techniques. Though he now works ashore, his interest in traditional rigging and sail training is greater than ever - so much so that he worked with the late Theo Rye in finalizing the design of Ilen’s rig to match the original from Conor O’Brien’s day, while ensuring that it is practical in modern terms both for requirements of efficiency and safety.

Captain Piers Alvarez’s current command is the 45-metre barque Kaskelot

Captain Piers Alvarez’s current command is the 45-metre barque Kaskelot

Piers Alvarez grew up in English cider country near the broad River Severn, but his personal horizons were far beyond apple growing. When he was 15, the captain of the famous square rigger Soren Larsen came to live in the village, which gave Piers’ father the opportunity to sign on his restless son as an Able Seaman at least for the duration of the school holidays, but the boy became hooked on the sea.

More than thirty years later, the love of seafaring and traditional ships is undimmed. Although Piers’ maritime career has also taken in tugs, superyachts and ice-classed research vessels, his current role in command of the Kaskelot perfectly chimes with his most passionate interests, and he has been fascinated by the entire Ilen project from an early stage.

So when the possibility arose of spending time in Limerick working along with his old shipmate Trevor Ross on the rigging for Ilen as a training project for the Ilen School’s intake, he readily gave up a week of his leave to teach the Ilen’s build team and future crew everything he knows, while moving a key part of the Ilen plan along the path of progress.

Piers Alvarez and trainee Elan Broadly busy with their work in Limerick

Piers Alvarez and trainee Elan Broadly busy with their work in Limerick

Ilen School Instructor James Madigan (left) with Piers Alvarez and Elan Broadly, immersed in their learning work while everyone else is on holiday. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Ilen School Instructor James Madigan (left) with Piers Alvarez and Elan Broadly, immersed in their learning work while everyone else is on holiday. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Team work. (Left to right) Liam O’Donoghue, James Madigan, and Elan Broadly on a steep learning curve with Piers Alvarez. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Team work. (Left to right) Liam O’Donoghue, James Madigan, and Elan Broadly on a steep learning curve with Piers Alvarez. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Modern amateur sailors, accustomed to today’s rigging where a terminal can be fitted in a seemingly-simple machine with the press of a button, can scarcely imagine the patient effort and skill which goes into making an eye splice in wire rigging which is of such a weight that, to most of us, it looks more like working with steel hawsers.

This is hard graft, but very rewarding in the result, and the satisfaction found in the effort expended. Much of it is done entirely by hand, but now and again that lethal multiple tool, the angle-grinder, will speed up a finishing job.

Some of the tools used in setting up traditional rigging are of very ancient origin…………….Photo: Gary MacMahon

Some of the tools used in setting up traditional rigging are of very ancient origin…………….Photo: Gary MacMahon

….but inevitably an angle grinder will be used at some stage, and Piers Alvarez is ace with it. Photo: Gary MacMahon

….but inevitably an angle grinder will be used at some stage, and Piers Alvarez is ace with it. Photo: Gary MacMahon

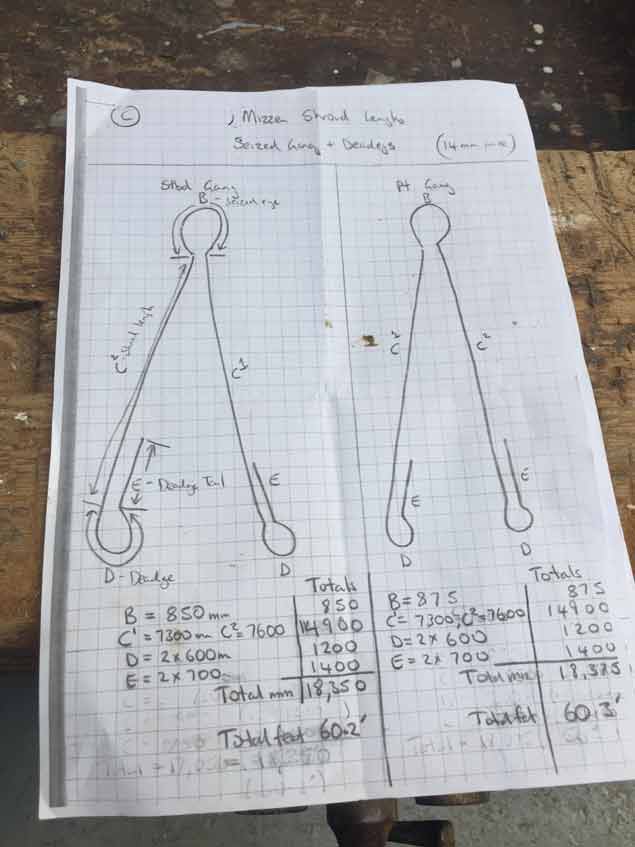

When finished, the neatly parcelled eye-spliced shrouds will fit the re-shaped mast like a glove, while at the other end, the shrouds will be tensioned by traditional lanyards through dead-eyes which have been made in Limerick from tough greenheart timber. It’s a long way from a drum of raw steel wire and a still squared hounds area to be progressed into something which will function on the massive mast in smooth partnership, providing Ilen with her sailing power. And in Limerick over the holiday week, it provided an unusually satisfying way to learn something new and useful.

With the simplest of work drawings, an experienced rigger can turn a piece of hefty steel wire into a serviceable piece of rigging. Photo: Gary MacMahon

With the simplest of work drawings, an experienced rigger can turn a piece of hefty steel wire into a serviceable piece of rigging. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The thick steel wire in its raw state is a daunting sight. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The thick steel wire in its raw state is a daunting sight. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The lower ends of the shrouds will be attached to the chainplates by lanyards rove through deadeyes made from greenheart, seen here at an early stage of the shaping process in Limerick. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The lower ends of the shrouds will be attached to the chainplates by lanyards rove through deadeyes made from greenheart, seen here at an early stage of the shaping process in Limerick. Photo: Gary MacMahon

“Series production” of dead-eyes. Photo: Gary MacMahon

“Series production” of dead-eyes. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Dead-eyes at the final stage of their creation. All that remains to be done is to shape grooves to allow a fair downward lead for the lanyards. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Dead-eyes at the final stage of their creation. All that remains to be done is to shape grooves to allow a fair downward lead for the lanyards. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Historic Ketch Ilen Seems Happy with her New Paint Job

There are those who think that attributing characteristics of sentient life to the appearance of a boat is quaint to the point of serious irritation writes W M Nixon. So those opposed to such hyper-anthropomorphism may as well look elsewhere from here on in.

The fact is, fans of the historic 56ft ketch Ilen currently being restored in the Cornstore building at Oldcourt Boatyard near Baltimore reckon that she’s smiling to herself in the new paint job she’s been acquiring in recent days, and they won’t hear it of it being explained in any other way.

Certainly when we look back to those early days of the restoration rather longer ago than most of us care to remember, and the way that every job completed revealed that two more needed to be done, it is surely a matter for a quiet smile of satisfaction that this stage has at last been reached. So maybe it’s time for us all to cheer up just a little bit and see the brighter side of life as personified in this new colour scheme.

A little bit done, a lot more to do…..shipwright Liam Hegarty (left) and Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Boatbuilding School at an early stage of the restoration, when the outlook was grim

A little bit done, a lot more to do…..shipwright Liam Hegarty (left) and Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Boatbuilding School at an early stage of the restoration, when the outlook was grim

Historic Boat Ilen Gets Her Colour Back, & It’s Mystifying…

The mood in the Corn Store at Oldcourt Boayard near Baltimore where the Conor O’Brien ketch Ilen is being restored may still be distinctly ghost-like writes W M Nixon. The old place would make a good setting for some tales of the otherworld even with clear air. But with the mist of busy spray-painting tingeing the scene, Ilen is emerging from her bare-wood state in a spectral climate where all things are possible.

And all things include the revelation of the final colour scheme chosen by Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Boatbuilding School. We’re told the 1927-built 57-footer will have blue-grey topsides, while the covering board and capping rail will be very soft grey, and the bulwarks will be white.

It has to be admitted it looks rather attractive. Subtle certainly. Yet I’m sure a majority in the Ilen/Afloat.ie poll voted for darkish green. I know I did, with the stipulation that she be given a classic white boot-top.

Ghost ship will sail again. Officially, Ilen is blue-grey hull, covering board and capping rail very soft grey, with bulwarks white. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Ghost ship will sail again. Officially, Ilen is blue-grey hull, covering board and capping rail very soft grey, with bulwarks white. Photo: Gary MacMahon

In conversation with the great voyager/mountaineer Paddy Barry last night, originally on another topic, it seemed he too had voted for the dark green. So much so, in fact, that it led to a discussion of the origins of the colour English Racing Green in international motor racing. The answer is: think Counties Wicklow and Kildare, and Gordon Bennett. But that’s by the way. Meanwhile, the news on Ilen is she’s a class of blue-grey. We’d better get used to it.