With hopes being expressed that we’re approaching peak COVID-19, there’s concern that people will relax their vigilance in maintaining the proven quarantine precautions, and that numbers will start to rise again. One of the most frighteningly effective ways of spreading the infection is through sneezing, and the US Navy – whose ships are potentially lethal Coronavirus-spreading incubation units – has made comprehensive laboratory tests.

These tests have demonstrated that a violent sneeze can actually spread the infective droplets by as much as eight metres – four times as far as the recommended two metres Safe Social Distancing that health authorities worldwide are recommending.

However, the technical videos which demonstrate this frightening reality look so much like some Computer Generated footage that they fail to make any real impact on a public already be-numbed with Government Information fact-sheets and films. So at Afloat.ie, we reckon that a graphic description of the effects of a monster sneeze is now more effective in capturing attention, and for the necessarily vivid account, we turn to the writings of a former Dublin Bay 21 sailor.

Patrick Campbell (1913-1980) was the son of Lord Glenavy, a noted Dublin polymath who was a Governor of the Bank of Ireland, a barrister, and an economist of international standing, while his mother Lady Glenavy was the artist Beatrice Elvery of the sports shops family. Their lively family life reflected their many talents, but young Patrick failed to settle into any lasting career, and in the end drifted into journalism, becoming for a while the Quidnunc who wrote the daily Irishman’s Diary in The Irish Times.

This was during the 1940s when life was lived in a more economical style. But having seen one of their houses burnt down by Anti-Treaty forces during the 1920 - an event of which Campbell was to write a brilliant account - the Glenavy family lived well during the 1930s, and while young Patrick was an unexpectedly good golfer (for he was something like 6ft 5ins tall, and awkward with it) he and his father – always simply referred to by the family as “The Lord” – were into several sports.

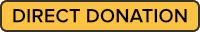

The launching of the new James Kelly-built Dublin Bay 21 Garavogue at Portrush in 1903. The original owner was W R Richardson. Photo courtesy Robin Ruddock

The launching of the new James Kelly-built Dublin Bay 21 Garavogue at Portrush in 1903. The original owner was W R Richardson. Photo courtesy Robin Ruddock

Sailing was one of them, and during the 1930s, The Lord owned and regularly raced the Dublin Bay 21 Garavogue, originally built by James Kelly of Portrush in 1903. She was well worn by the 1930s, thus it was Lord Glenavy who – at a Committee Meeting of the Royal Alfred Yacht Club in 1934 – first suggested the formation of a new, larger Bermuda-rigged One-design class for Dublin Bay.

This in time became the Dublin Bay 24s. But as the interruptions of World War II meant they didn’t have their first race until 1947, by this time Glenavy was getting near the end of his sailing career, and it concluded with the sale of Garavogue. Nevertheless, during his time with the boat, he and his family were very much involved with the class, and in his later writing, Patrick Campbell recalled how, on the rare enough occasions when Garavogue did very well, his father would exasperatingly delay going ashore after racing in order to take time out to mark all sheets with bits of brightly-coloured wool to show exactly how the sails had been trimmed when the boat was winning.

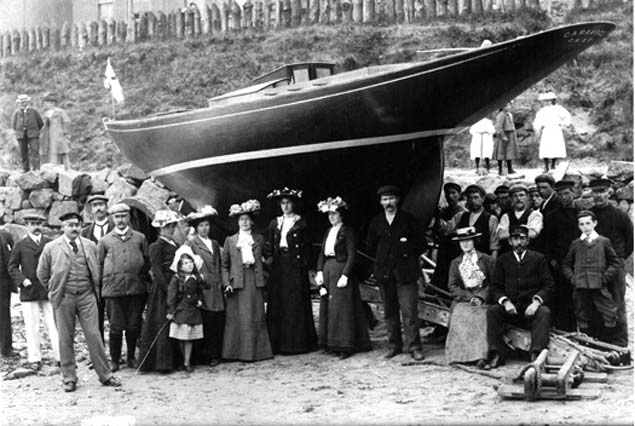

Plans for the Dublin Bay 24. The concept for a new class was originally suggested by Lord Glenavy at a Committee Meeting of the Royal Alfred YC in Dun Laoghaire in 1934, but by the time these plans were finally agreed and construction had started, World War II was looming, and the class was not to race in Dublin Bay until 1947.

Plans for the Dublin Bay 24. The concept for a new class was originally suggested by Lord Glenavy at a Committee Meeting of the Royal Alfred YC in Dun Laoghaire in 1934, but by the time these plans were finally agreed and construction had started, World War II was looming, and the class was not to race in Dublin Bay until 1947.

Needless to say, despite meticulously replicating the sail trim next time out, Garavogue would disappointingly fail to perform. But the boat and the class provided a source of anecdotes for Patrick Campbell’s subsequent humorous writing, with the annual Wicklow Regatta in particular providing a rich seam of narrative.

Long after he’d left Ireland to work first in England and then base himself happily with his third wife in the south of France while still continuing to produce gems of style and wit, he heard from Dublin Bay 21 enthusiast Fionan de Barra that Garavogue was still very much in existence, and wrote back with a contribution for a book (which will appear in due course) on the Dublin Bay 21s, and telling of his pleasure of learning of the boat’s continuing life, as he had long since assumed she’d become “a sturdy hen-house”.

Rather more than “a sturdy hen-house”. The exquisitely-restored hull interior of Garavogue as seen in Kilrush Boatyard last September. Photo: W M Nixon

Rather more than “a sturdy hen-house”. The exquisitely-restored hull interior of Garavogue as seen in Kilrush Boatyard last September. Photo: W M Nixon

In later years, his career blossomed, for although he’d been educated in England, he never lost his Irish accent which was emphasized in television appearances (he was a star of panel and game shows), a pleasant accent which was emphasised by his sometimes total stammer, which he preferred to describe as “an attractive speech impediment”. He would emerge as cool as you please from ferocious bouts with it, while everyone around him had been reduced to acute nervous tension.

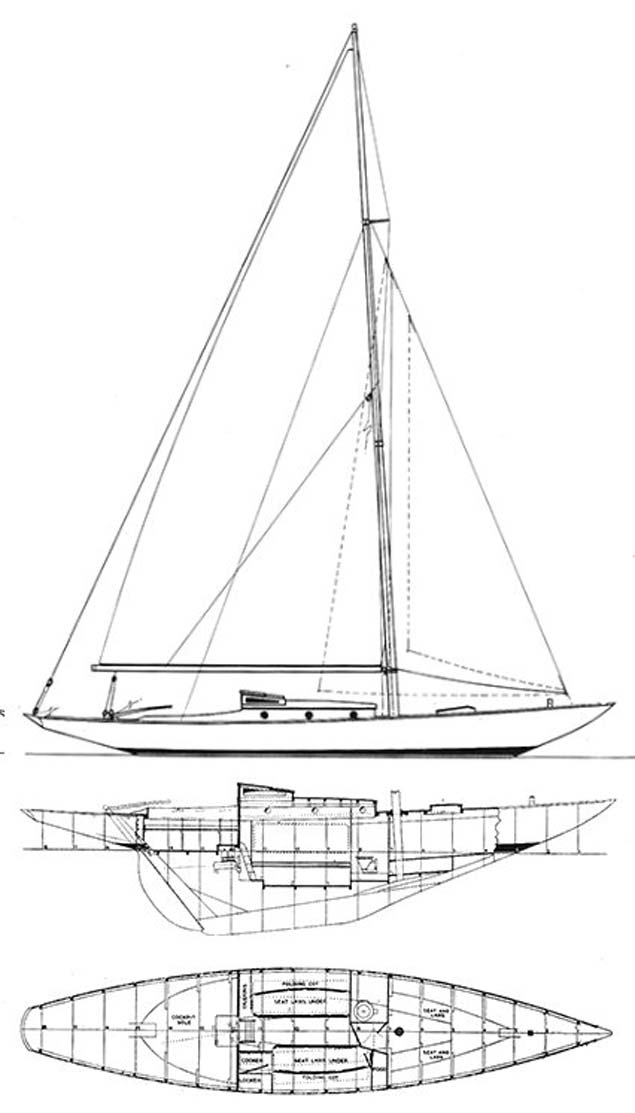

Dublin Bay 21 sailor Patrick Campbell. He eventually found his metier as a “universal humorous writer” and a television performer, noted on screen for his relaxing Irish accent and a stammer which he preferred to think of as “an attractive speech impediment”

Dublin Bay 21 sailor Patrick Campbell. He eventually found his metier as a “universal humorous writer” and a television performer, noted on screen for his relaxing Irish accent and a stammer which he preferred to think of as “an attractive speech impediment”

In his extensive writings he wasn’t above a bit of Paddywhackery when writing about his erstwhile countrymen, which may partially explain who he is no longer as well-known here as he should be. But in mitigation, it should be said that the Paddy who was dealt the greatest whackery in his often wickedly funny writing was Paddy Campbell himself.

And ultimately he was Everyman, faced with the problems of being an accident-prone giant struggling to get through life with a modicum of dignity and subsequent humour. Thus although this piece – A Stallion Sneeze - about the hazards of extreme sneezing from the early 1960s begins with a reference to King’s Road in Chelsea at a time when Swinging London was coming to life, it was written in France, it is universal in its relevance, and it is very timely for our current situation.

A STALLION SNEEZE

I had written:

‘At eight o’clock on a Sunday morning King’s Road in Chelsea is a desolate waste of litter – old newspapers, ice cream cartons, torn shopping bags, cigarette ends by the million -’

Then I got this tremendous sneeze.

It was one of those sneezes the preliminaries of which seem to go on for ever. At one minute I was sitting there writing about litter in Chelsea and the next I was in the grip of a cosmic force so powerful that without straining itself in any way it began to change my whole physical shape. I began to feel like putty being moulded by a huge glazier.

First, this giant force got to work upon my jaws and mouth, pressing out and hardening this delicate machinery until, with the teeth bared and the upper lip drawn back, I must have looked like Silver, the mad white stallion, about to do something unpleasant.

At the same time this frightful pressure squeezed my eyes shut and then shoved them along the Eustachian tubes into my ears, where they flung themselves against the drums, trying to get out.

This displacement of the eyes led almost immediately to a change in the shape of the top of my head. It began to rise into a point, with the subsidiary effect of drawing me right up into the top left-hand corner of my high-backed chair, so that it seemed that I retained a grip upon the floor only with a single toe.

For some time I held this pose, levitating, teeth bared, lips curled, nostrils flaring, ears gone, eyes bursting and nails dug deep into the upholstery. Then everything blew up.

The actual explosion was preceded by a wild cry of mindless terror – a long drawn out yell sounding something like ‘AAAAAAGH’ – and then it burst.

I was surprised by the damage, except of course that the circumstances were rather special.

Just before I’d written the words about the litter in King’s Road I’d slipped half a large tomato, peppered and salted, into my mouth, where it joined a partially chumbled biscotte – one of those roasted bread slices which the French do so well. Into this mixture I then injected a mouthful – or as much of a mouthful as possible – of black coffee.

It was a tight fit but it would have been a viable proposition if it hadn’t been for the sneeze.

The whole business – typing with the mouth bursting with breakfast – came from being suddenly seized with an idea, after being dazzled for too long by the glare of an empty page. I felt I needed this last mouthful of breakfast, to sustain me, while at the same time rattling out the first sentence, before it got away.

Anyway, it burst.

For a moment I thought I’d blown the front of my face off. There was this awful feeling of everything coming away. I almost got my handkerchief to the site of the explosion and then there came another one, louder, wilder, infinitely more destructive than the first.

I lay back in my chair, spent, drained of everything, waiting for the third eruption – the one which would deprive me of my backbone, shooting it out through my nose in a spray of tinkling vertebrae which would probably smash the window on the other side of the room.

It turned out that we’d finished. These two major explosions, one even bigger than the other, were to be our portion for the day.

But at what a cost.

The extremely high muzzle velocity of the breakfast had enabled it to reach and to penetrate every corner and crevice of the room. It had got to the bookshelf and the Modigliani reproduction above it. It was on the door, the ceiling and all four walls. It was in the typewriter. It had even struck a portrait of me painted by an aunt of mine in 1954, where it had obliterated one eye. The other one stared at me in outrage.

I sat there, huddled in my chair, tomatoed, thinking what bad luck it all was. I was thinking that if Tolstoy had got one of those we wouldn’t have had War and Peace. A couple of those for Dickens would have meant curtains for both Dombey and his son.

I set to to clean up, sorry for the world that now would never hear about the surprising amount of litter in King’s Road at eight o’clock on a Sunday morning.

The Dublin Bay 21 Class racing, with Naneen – now restored for Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra – in the foreground. On the rare enough occasions when the Campbell family’s Garavogue did well, Lord Glenavy would keep everyone waiting while he used brightly-coloured wool to mark the exact setting of each sheet. Despite his efforts, almost invariably the excellent performance would not be repeated on the next outing, even with the sheets being trimmed precisely as they’d been when success was achieved

The Dublin Bay 21 Class racing, with Naneen – now restored for Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra – in the foreground. On the rare enough occasions when the Campbell family’s Garavogue did well, Lord Glenavy would keep everyone waiting while he used brightly-coloured wool to mark the exact setting of each sheet. Despite his efforts, almost invariably the excellent performance would not be repeated on the next outing, even with the sheets being trimmed precisely as they’d been when success was achieved