Displaying items by tag: Copper Coast

Irish Cruising Comes Centre Stage In Howth Yacht Club

With last night’s Irish Cruising Club Annual General Meeting & Prize-Giving hosted at Howth Yacht Club, and this morning’s day-long ISA Cruising Conference at the same venue, centre stage has been taken by the silent majority – the large but distinctly reticent segment of the sailing population which emphatically does not have racing as its primary interest afloat. W M Nixon takes us on a guided tour.

The great Leif Eriksson would approve of some of the more adventurous members of the Irish Cruising Club. They seem to be obsessed with sailing to Greenland and cruising along its coast. And it was the doughty Viking’s father Erik Thorvaldsson (aka Erik the Red) who first told his fellow Icelanders that he’d given the name of Greenland to the enormous island he’d discovered far to the west of Iceland. He did so because he claimed much of it was so lush and fertile, with huge potential for rural and coastal development, that no other name would do.

Leif then followed in the family tradition of going completely over the top in naming newly-discovered real estate. He went even further west and discovered a foggy cold part of the American mainland which he promptly named Vinland, as he claimed the area was just one potential classic wine chateau after another, and hadn’t he brought back the vines to prove it?

In time, Erik’s enthusiasm for Greenland was seen as an early property scam. For no sooner had the Icelanders established a little settlement there around 1000 AD than a period of Arctic cooling began to set in, and by the mid-1300s there’d been a serious deterioration of the climate. What had been a Scandinavian population of maybe five thousands at its peak faded away, and gradually the Inuit people – originally from the American mainland – moved south from their first beachheads established to the northwest around 1200 AD. They proved more successful at adapting to what had become a Little Ice Age, while no Vikings were left.

Now we’re in the era of global warming, and there’s no doubt that Greenland is more accessible. But for those of us who think that cruising should be a matter of making yourself as comfortable as possible while your boats sails briskly across the sea in a temperate climate or perhaps even warmer for preference, the notion of devoting a summer to sailing to Greenland and taking on the challenge of its rugged iron coast, with ice everywhere, still takes a bit of getting used to.

Yet in recent years the Irish boats seem to have been tripping over each other up there. And for some true aficionados, the lure of the icy regions was in place long before the effects of global warming were visibly making it more accessible.

Peter Killen of Malahide, Commodore of the Irish Cruising Club, is a flag officer who leads by example. It was all of twenty years ago that he was first in Greenland with his Sigma 36 Black Pepper, and truly there was a lot of ice about. The weather was also dreadful, while Ireland was enjoying the best summer in years.

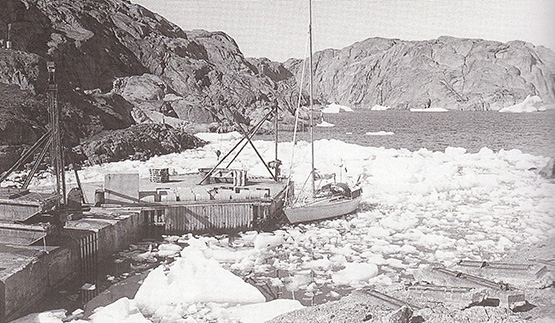

Peter Killen’s Sigma 36 Black Pepper in local ice at the quay inside Cape Farewell in Greenland, August 1995

ICC Commodore Peter Killen’s current boat is Pure Magic, an Amel Super Maramu seen here providing the backdrop for a fine penguin in Antarctica, December 2004.

More recently, he and his crew of longterm shipmates have been covering thousands of sea miles in the Amel Super Maramu 54 Pure Magic, among other ventures having a look at lots more ice down Antarctic way to see how it compares with the Arctic. With all their wanderings, by the end of the 2014 season Pure Magic was laid up for the winter in eastern Canada in Nova Scotia. So of course in order to get back to Ireland through 2015, the only way was with a long diversion up the west coast of Greenland. And the weather was grand, while Ireland definitely wasn’t enjoying the best summer in years.

The Pure Magic team certainly believe in enjoying their cruising, however rugged the terrain. If the Greenland Tourist Board are looking for a marketing manager, they could do no better than sign up the skipper of Pure Magic for the job. His entertaining log about cruising the region – featured in the usual impressive ICC Annual edited for the fourth time by Ed Wheeler – makes West Greenland seem a fun place with heaps of hospitality and friendly folk from one end to the other.

If ice is your thing, then this is the place to be – Peter Killen’s Pure Magic off the west Greenland coast, summer 2015.

But then Peter Killen is not as other men. I don’t mean he is some sort of alien being from the planet Zog. Or at least he isn’t so far as I know. But the fact is, he just doesn’t seem to feel the cold. I sailed with him on a raw Autumn day some years ago, and while the rest of us were piling on the layers, our skipper was as happy as Larry in a short-sleeved shirt.

I’d been thinking my memory had exaggerated this immunity to cold. But there sure enough in the latest ICC Annual is a photo of the crew of Pure Magic enjoying a visit to the little Katersugaasivik Museum in Nuuk, and the bould skipper is in what could well be the same skimpy outfit he was wearing when we sailed together all those years ago. As for the rest of the group, only tough nut Hugh Barry isn’t wearing a jacket of some sort – even Aqqala the Museum curator is wearing one.

Some folk feel the cold more than others – Pure Magic’s crew absorbing local culture in Greenland are (left to right) Mike Alexander, Peter Killen, Hugh Barry, Aqqalu the museum curator, Robert Barker, and Joe Phelan

Having a skipper with this immunity to cold proved to be a Godsend before they left Greenland waters, when Pure Magic picked up a fishing net in her prop while motoring in a calm. Peter Killen has carried a wetsuit for emergencies for years, and finally it was used. He hauled it on, plunged in with breathing gear in action, and had the foul-up cleared in twenty minutes. Other skipper and Commodores please note……

The adjudicator for the 2015 logs was Hilary Keatinge, who has one of those choice-of-gender names which might confuse, so it’s good news to reveal that after 85 years, the ICC has had its first woman adjudicator. No better one for the job, man or woman. Before marrying the late Bill Keatinge, she was Hilary Roche, daughter of Terry Roche of Dun Laoghaire who cruised the entire coastline of Europe in a twenty year odyssey of successive summers, and his daughter has proven herself a formidable cruising person, a noted narrator of cruising experiences, and a successful writer of cruising guides and histories.

Nevertheless even she admitted last night that once all the material has arrived on the adjudicator’s screen, she finally appreciated the enormity of the task at hand, for the Irish Cruising Club just seems to go from strength to strength. Yet although it’s a club which limits itself to 550 members as anything beyond that would result in administrative overload and the lowering of standards, it ensures that the experience of its members benefit the entire sailing community through its regularly up-dated sailing directions for the entire coast of Ireland. And there’s overlap with the wider membership of the Cruising Association of Ireland, which will add extra talent to the expert lineup providing a host of information and guidance at today’s ISA Cruising Conference.

But that’s this morning’s work. Meanwhile last night’s dispensation of the silverware – some of which dates back to 1931 – revealed an extraordinarily active membership. And while they did have those hardy souls who ventured into icy regions, there were many others who went to places where the only ice within thousands of miles was in the nearest fridge, and instead of bare rocky mountains they cruised lush green coasts.

Nevertheless the ice men have it in terms of some of the top awards, as Hilary Keatinge has given the Atlantic Trophy for the best cruise with a passage of more than a thousand miles to the 4194 mile cruise of Peter Killen’s Pure Magic from Halifax to Nova Scotia to Howth, with those many diversions on the way, while the Strangford Cup for an alternative best cruise goes to Paddy Barry, who set forth from Poolbeg in the heart of Dublin Port, and by the time he’d returned he’d completed his “North Atlantic Crescent”, first to the Faeroes, then Iceland to port, then across the Denmark Strait to southeast Greenland for detailed cruising and mountaineering, then eventually towards Ireland but leaving Iceland to port, so they circumnavigated it in the midst of greater enterprises.

You collect very few courtesy ensigns in the frozen north. Back at Poolbeg in Dublin after her “North Atlantic Crescent” round Iceland and on to Greenland, Paddy Barry’s Ar Seachran sports the flags of the Faroes, Iceland and Greenland. Ar Seachran is a 1979 alloy-built Frers 45. Photo: Tony Brown

“Definitely the Arctic”. A polar bear spotted from Ar Seachran. Photo: Ronan O Caoimh

Paddy Barry started his epic ocean voyaging many years ago with the Galway Hooker St Patrick, but his cruising boat these days is very different, a classic Frers 45 offshore racer of 1979 vintage. Probably the last thing the Frers team were thinking when they turned out a whole range of these gorgeous performance boats thirty-five years ago was that their aluminium hulls would prove ideal for getting quickly to icy regions, and then coping with sea ice of all shapes and ices once they got there. But not only does Paddy Barry’s Ar Seacrhran do it with aplomb, so too does Jamie Young’s slightly larger sister, the Frers 49 Killary Flyer (ex Hesperia ex Noryema XI) from Connacht, whose later adventures in West Greenland featured recently in a TG4 documentary.

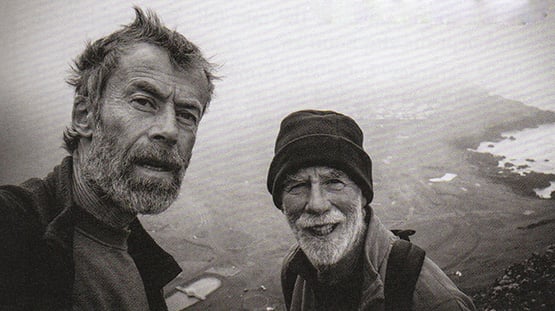

“A grand soft day in Iceland”. Harry Connolly and Paddy Barry setting out to take on mountains in Iceland during their award-winning cruise to Greenland. Photo: Harry Connolly

Pure Magic and Ar Seachran are hefty big boats, but the other ICC voyager rewarded last night by Hilary Keatinge for getting to Arctic waters did his cruise in the Lady Kate, a boat so ordinary you’d scarcely notice her were it not for the fact that she’s kept in exceptionally good trim.

Drive along in summer past the inner harbour at Dungarvan in West Waterford at low water, and you’ll inevitably be distracted by the number of locally-based bilge-keelers sitting serenely upright (more or less) on that famous Dungarvan mud. There amongst them might be the Moody 31 Lady Kate, for Dungarvan is her home port.

But she was away for quite a while last year, as Donal Walsh took her on an extraordinary cruise to the Arctic, going west of the British mainland then on via Orkney and Shetland to Norway whose coast goes on for ever until you reach the Artic Circle where the doughty Donal had a swim, as one does, and looked at a glacier or too, and then sailed home but this this time leaving the British mainland to starboard. A fabulous 3,500 mile eleven week cruise, he very deservedly was awarded the Fingal Cup for a venture the adjudicator reckons to be extra special – as she puts it, “you feel you’re part of the crew, though I don’t think I’d have done the Arctic Circle swim.”

A long way from Dungarvan. Lady Kate with Donal Walsh off the Svartsen Glacier in northern Norway

Indeed, in taking an overview of the placings of the awards, you can reasonable conclude that the adjudicator reckons any civilized person can have enough of ice cruising, as she gives the ICC’s premier trophy, the Faulkner Cup, to a classic Atlantic triangle cruise to the Azores made from Dun Laoghaire by Alan Rountree with his van de Sadt-designed Legend 34 Tallulah, a boat of 1987 vintage which he completed himself (to a very high standard) from a hull made in Dublin by BJ Marine.

Tallulah looks as immaculate as ever, as we all saw at the Cruising Association of Ireland rally in Dublin’s River Liffey in September. And this is something of a special year for Alan Rountree, as completely independently of the Faulkner Cup award, the East Coast ICC members awarded their own area trophy, the Donegan Cup for longterm achievement, to Tallulah’s skipper. As one of those involved in the decision put it, basically he got the Donegan Trophy “for being Alan Rountree – what more can be said?”

The essence of the Azores. Red roofs maybe, but not an iceberg in sight, and the green is even greener than Ireland. Alan Rountree’s succesful return cruise to the Azores has been awarded the ICC’s premier trophy, the Faulkner Cup.

Tallulah at the CAI Rally in the Liffey last Setpember. She looks as good today as when Alan Rountree completed her from a bare hull nearly thirty years ago. Photo: W M Nixon

A boat to get you there – and back again. Tallulah takes her departure from the CAI Rally in Dublin. Photo: Aidan Coughlan

Well, it can be said that his Azores cruise was quietly courageous, for although the weather was fine in the islands, the nearer he got to Ireland the more unsettled it became, and he sailed with the recollection of Tallulah being rolled through 360 degrees as she crossed the Continental Shelf in a storm in 1991. But he simply plodded on through calm and storm, the job was done, and Tallulah is the latest recipient of a trophy which embodies the history of modern Irish cruising.

There were many other awards distributed last night, and for those who think that the ICC is all about enormous expensively-equipped boats, let it be recorded that the Marie Trophy for a best cruise in a boat under 30ft long went to Conor O’Byrne of Galway who sailed to the Hebrides with his Sadler 26 Calico Jack, while the Fortnight Cup was taken by a 32-footer, Harry Whelehan’s Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 32 for a fascinating cruise in detail round the Irish Sea, an area in which, the further east you get to coastlines known to very few Irish cruising men, then the bigger the tides become with very demanding challenges in the pilotage stales.

The smallest boat to be awarded a trophy at last night's Irish Cruising Club prize-giving was Conor O’Byrne’s Sadler 26 Calico Jack, seen here in Tobermory during her cruise from Connacht to the Hebrides

As for “expensively equipped”, the Rockabill Trophy for seamanship went to Paul Cooper, former Commodore of Clontarf Yacht & Boat Club and an ICC member for 32 years, who solved a series of very threatening problems with guts and ingenuity aboard someone else’s Spray replica during a 1500 mile voyage in the Caribbean, with very major problems being skillfully solved, as the judge observed, “without a cross word being spoken”.

Not surprisingly in view of the weather Ireland experienced for much of the season, there were no contenders for the Round Ireland cruise trophy, though I suppose you could argue that the return of Pure Magic meant the completion of a round Ireland venture, even if in this case the Emerald Isle becomes no more than a mark of the course.

In fact, with the unsettled weather conditions of recent summers in Ireland , there’s now quite a substantial group of ICC boats based out in Galicia in northwest Spain, where the mood of the coast and the weather “is like Ireland only better”. The ICC Annual gives us a glimpse of the activities of these exiles, and one of the most interesting photos in it is provided by Peter Haden of Ballyvaughan in County Clare, whose 36ft Westerly Seahawk Papageno has been based among the Galician rias for many years now.

Down there, the Irish cruising colony can even do a spot of racing provided it’s against interesting local tradtional boats, and Peter’s photo is of Dermod Lovett of Cork going flat out in his classic Salar 40 Lonehort against one of the local Dorna Xeiteras, which we’re told is the Galician equivalent of a Galway Bay gleoiteog. Whatever, neither boat in the photo is giving an inch.

So who never races? Dermod Lovett ICC in competition with his Salar 40 Lonehort against a local traditional Dorna Xeiteira among the rias of northwest Spain. Photo: Peter Haden

Hilary Keatinge’s adjudication is a delight to read in itself, and last night after just about every sailing centre in Ireland was honoured with an ICC award for one of its locally-based members, naturally the crews leapt to the mainbrace and great was the splicing thereof.

But it’s back to porridge this morning in HYC and the serious work of the ISA Cruising Conference, where the range of topics is clearly of great interest, for the Conference was booked out within a very short time of being highlighted on the Afloat.ie website.

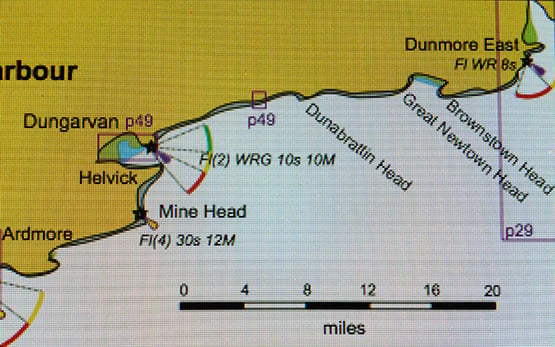

It’s during it that we’ll hear more about that intriguing little anchorage which provides our header photo, for although it could well be somewhere on the Algarve in Portugal, or even in the Ionian islands in Greece were it not for the evidence of tide, it is in fact on the Copper Coast of south Waterford, between Dungarvan and Dunmore East, and it’s known as Blind Harbour.

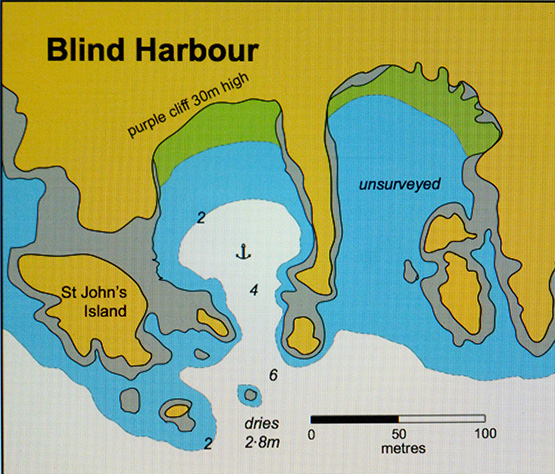

It’s a charming place if you’ve very settled weather, but it’s so small that you’d probably need to moor bow and stern if you were thinking to overnight, but that’s not really recommended anyway. Norman Kean, Editor of the Irish Cruising Club Sailing Directions, had heard about this intriguing little spot from Donal Walsh of Dungarvan (he who has just been awarded the Fingal Cup), and being Norman Kean, he and Geraldine just had to go and experience it for themselves. But it has taken three attempts to have the right conditions as they were sailing by, and it happened in 2015 in a very brief period of settled weather as they headed past in their recently-acquired Warrior 40 Coire Uisge, which has become the new flagship of the ICC’s informal survey flotilla.

The secret cove is to be found on Waterford’s Copper Coast, midway between Dungarvan and Dunmore East. Courtesy ICC

The newly-surveyed Blind Harbour on the Waterford coast as it appears in the latest edition of the ICC’s South & West Coasts Sailing Directions published this month. Courtesy ICC.

They found they’d to eye-ball their way in to this particular Blind Harbour (there are others so-named around the Irish coast) using the echo sounder, as any reliance on electronic chart assistance would have had them on the nearest part of County Waterford, albeit by only a matter of feet. With a similar exercise a couple of years ago, they found that the same thing was the case at the Joyce Sound Pass inside Slyne head in Connemara – rely in the chart plotter, and you’re making the pilotage into “impactive navigation”.

The message is that some parts of charts are still relying on surveys from a very long time ago, and locations of hyper-narrow channels may be a few metres away from where they actually are. On the other hand, electronic anomalies may arise. Whatever the reason, I know that a couple of years ago, in testing the ship’s gallant little chart plotter we headed for the tricky-enough Gillet passage inside the South Briggs at the south side of the entrance to Belfast Lough, and found that it indicated the rocks as shown were a tiny bit further north than we were seeing, which could have caused a but of a bump if we’d continued on our electronic way.

Electronic charts are only one of many topics which will be covered today. We hope to bring a full report next Saturday, for the participants will in turn require a day or two to digest their findings.