Displaying items by tag: John Lavery

Ireland’s Fireball Dinghy Class Provided The Secret Of Eternal Youth

You’ll have glimpsed the photo gallery and heard the reports of the International Fireball Dinghy Class 50th Anniversary Irish Reunion last Saturday night in the Royal St George YC in Dun Laoghaire. Fifty years, by George……Most sailing folk still think of the Fireball as a fresh and unique off-the-wall sailing phenomenon, a crazy European take on the skimming-dish scows of the lakes of America’s mid-West. And we think of these very special racing dinghies as being something as new as tomorrow, ingenious boats for ingenious owners who like to do all sorts of personal tunings and tweaks to their pride-and-joy. So it brings us up short to find them celebrating their Golden Jubilee. W M Nixon gives his own take on the Former Fireball Fanatics.

If you’re from anywhere well outside the bubble which is southeast Dublin, you’ll assume that a group of guys who regularly drink in a place called the Tramyard will be a bunch of winos. But those in the know are well aware that the Tramyard in Dalkey is a more-than-agreeable coffee house where a regular group of morning habituees supping the essence of the sacred bean is a gathering of sailing friends who have been mates since studying in college or whatever they were doing at that exciting time of life, when all things were possible, and just to have an idea was enough to have the energy to implement it and do something with the result.

The inspiration for the Fireball design more than fifty years ago came partially from the classic scows of the lakes of mid-western America. This is a Melges Class A Scow.

As this Tramyard crowd have been regularly together for so long, they have not noticed the effects of the passing of the years on each other. So when Derek Jago got to reflecting among them last Autumn that maybe their best sailing years were spent in the Fireball Class, and that it was amazing to think it had been around for fifty years, former Fireball champion Brian Craig immediately suggested that if Derek would organise a post-50th Anniversary Reunion of the Irish Fireball Class past and present, then he – Brian - would see about making the Royal St George Yacht Club available as the venue, for after all it was the George – home club for most of them - which had the biggest Fireball fleet in the great days of the class’s Irish glory.

The party happens – Derek Jago (left) with former Fireballers Howard Knott, Peter Stapleton and Hilary Knott. Photo: Fotosail

Of course, when you do organise something like this, you will know what your own close circle of old friends now look like. But it’s a fascinating exercise in the observation of the aging process to wheel in people you mightn’t have seen in thirty and more years.

In fact, it might have been fraught with a certain risk of non-recognition of faces from the distant past. But the Irish Fireball Class was not only an outstanding success in its peak years, it went on to send out rising stars who were to make their mark in many other areas of sailing. Consequently last Saturday night proved to be a gathering of familiar faces of whom, in some cases, folk were saying: “But I never knew you were ever a Fireball sailor”.

Yet not only were they Fireball sailors once upon a time, but they were very proud of the fact. For in the nicest possible way, the Fireball was and is a bit of a cult thing. She was designed by Peter Milne, who at the time of her creation was working on the drawings for the latest Donald Campbell world water speed record challenger. In the midst of such a hothouse of technology and massive expenditure, it seemed like a breath of fresh air to take a little time out to create a boat which reduced sailing to its absolute essentials, and he did it so well that Peter Milne thereafter never quite matched this one divine inspiration.

And it was truly inspirational. After all, who would have thought that a minimalist boat, with just about zero freeboard and skinny with it, and with her slim hull further reduced in volume by having a cut-off pram bow, who could have thought it would be such a superb sailing machine when she’d a crew who gave total commitment to the concept and realized that the use of the trapeze was what Fireball sailing was all about?

The first in Ireland –Roy Dickson’s No 38 making a tentative visit to Dun Laoghaire in September 1962.

Champions – Roy Dickson crewed by David Lovegrove after successfully defending the Fireball Nationals in 1966.

Well, the first in Ireland was Roy Dickson of Kilbarrack and Sutton on the north shores of Dublin Bay, a man who cannot contemplate any boat without thinking about ways of improving it. He’d already been taking several sails on the wild side by building a Jack Holt-designed 16ft Hornet with a sliding seat in the manner of Uffa Fox’s famous sailing canoes, so when the design of the Fireball first appeared in Yachts & Yachting magazine in 1962, it was a eureka moment.

Roy’s first Fireball, no 38, made a tentative appearance across Dublin Bay in Dun Laoghaire at the end of the 1962 season, and next Spring it was revealed that other sailors from the north shore were following in his footsteps. They’d already set up a class association with Peter O’Brien as Chairman and Eddie Kay as Honorary Secretary, and it was expected that up to 20 Fireballs would be racing in Ireland by the end of the 1963 summer.

The founding father – Roy Dickson with his sons Ian (left) and David on Saturday night at the celebration of the Irish Fireball Class. Photo: Fotosail

Jan van der Puil (left) with 1995 World Champion John Lavery. Photo: Fotosail

Early days – at an IYA Easter Meeting in Wexford the new Fireballs cut a dash by comparison with the older IDRA 14 and Enterprise in the background. Photo: W M Nixon

Celebrating the Fireball – Anthony and Sally O’Leary, with Cathy McAleavey and Con Murphy. Photo: Fotosail

It was an extraordinary breakthrough, the memory of it all made even more vibrant by the fact that Roy Dickson himself was there in Dun Laoghaire last Saturday night, his innovative Fireball years recalled as just another chapter in his own fantastic sailing career, which has gone right to the top both inshore and offshore.

The Fireball spoke eloquently to several successive waves of Irish sailors, and in the period between the mid 1960s and the late 1990s, you’d be hard put to say just what was the key year, with an early dose of extreme excitement being the Fireball Worlds at Fenit on Tralee Bay in 1970, John Caig from England being the winner. For although an unmatched high was reached in 1995 when John Lavery and David O’Brien of the National YC won both the Europeans and the Worlds in a mega regatta staged by their home club on Dublin Bay, at other times Adrian and Maeve Bell from the north – they were with Lough Neagh SC at the time - were very much in the international frame, counting many major titles.

Fireballs on an early outing to Sligo, where the Worlds were staged in 2011.

As for staging Fireball World Championships, Ireland has stepped up to the plate four times, with a particularly epic Worlds in Kinsale in 1977 where the Godkin brothers set the pace in the local fleet. Then there was the glorious home win at Dun Laoghaire in 1995. And the most recent Worlds in Ireland were at Sligo in 2011, where the great Gus Henry may have been best known as a stalwart of the GP 14 Class, but he too is a top sailor who savoured the Fireball experience.

At the height of the class’s popularity, nearly three quarters of the boats in Ireland were said to be an own-build, and Roy Dickson was the pace-setter in innovation. It’s said that if Roy turned up at a major international regatta with some completely new but barely perceptible additional feature on his boat, by the next championship you could be reasonably sure that at least half the fleet would have copied him.

But for some years now the class has seen plastic boats in the ascendant, which restrains the innovators. And numbers in Ireland are admittedly no longer so spectacular, for in its top years the truly active Fireball fleet here numbered 70 boats, which for an out-and-out performance dinghy was quite something.

There’s still as little bulk to the boat as possible, but they’re now built in GRP, as seen here with Frank Miller's boat at the Volvo Dun Laoghaire Regatta. Photo: VDLR

Yet while the fleets are reduced, the memories if anything are stronger than ever. The photos reveal the calibre of the people who were and are involved in Fireball racing in Ireland – it’s a national Who’s Who of sport afloat. And if that weren’t enough, the roll call of those who preceded John Lavery and David O’Brien in the intense battles to win the World Championship is of truly global stature in international sailing.

The first one of all in 1966 was Bob Fisher, no less, crewed by Richard Beales. Then Steve Benjamin of the US was in fine form in the 1970s, as he won in ’76 and then defended successfully at Kinsale in 1977. But in 1978 at Pattaya in Thailand, a new name came centre stage – the one and only Lawrie Smith. Then in 1981 the Worlds winner was future top dinghy designer Phil Morrison, with Fireball mods and tuning worthy of Roy Dickson.

Current Irish Fireball Class Chairperson, seen speaking at last Saturday’s party, is Marie J Barry. Photo: Fotosail

In 1994 it was ace sailmaker and multi-champion Ian Pinnell who won the Fireball Worlds, and this set the bar high for John Lavery and David O’Brien in Dublin Bay in 1995. Faced with the challenge, they implemented a rigorous two-year training and competition programme in the countdown to the big one, and it all came out as planned.

As the Fireball Worlds 1995 were staged in September, the rest of the Irish sailing community were well home from holidays and back at the day job, so those driving home from work on the Friday night heard it on the car radio as one of the top stories on the evening sports news. Ireland had won a world title. Better still, it was in sailing too. And it was on the peaktime national news. It was a moment to be recalled and savoured many times in Dun Laoghaire last Saturday night.

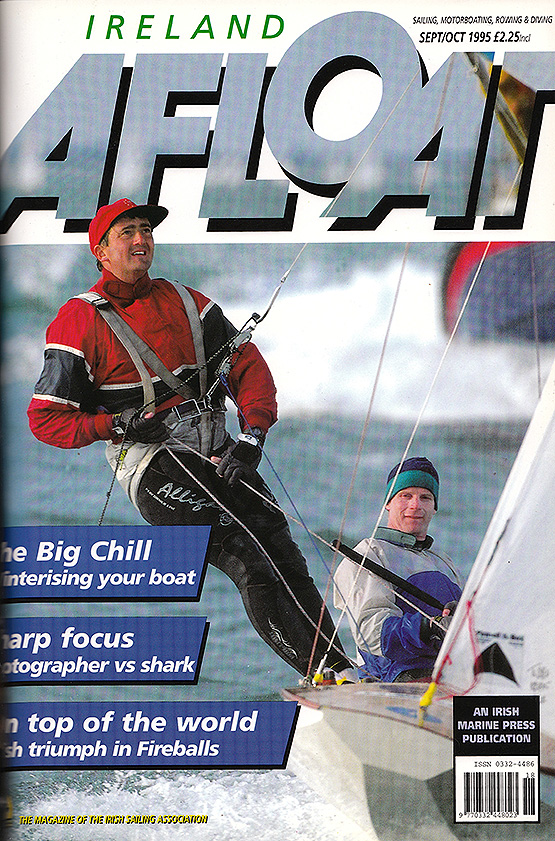

We can always use a cover like this – welcome news with David O’Brien and John Lavery from the Sept/Oct 1995 Afloat.

See full Fireball 50th photo gallery by Gareth Craig of Fotosail here