Displaying items by tag: Phil Morrison

National 18s Take Dinghy Racing Class Onto A New Plane

#national18 – There are some special dinghy classes. There are some very special dinghy classes. And then there are the National 18s.

You can see any number of reasons why this unique class, celebrating its 80th birthday in just three years time, is in a league of its own. A three-man boat with one of the crew on a trapeze, its crewing set–up requires a level of sociability which is further emphasised ashore, where their après sailing is the stuff of legend.

At all the centres where it is sailed, and at places upon which the National 18s have descended for a championship, we know they've left behind a formidable reputation for determined but good humoured conviviality, combined with great sportsmanship.

Yet while it is easy to understand the class's popularity among its adherents when you see them in high spirits as a group, there's no getting away from the fact that in today's dinghy terms, 18ft is a lot of boat. The mood of the National 18s may often seem light-hearted. But keeping one of these boats in prime condition and well crewed is not something for the casually-interested.

It requires real commitment, yet that is something which National 18 sailors seem to have in spades. And now the class has taken on a new lease of life with the development of a fresh take on the National 18 parameters by legendary designer Phil Morrison. But rather than being launched as a commercial venture, the new boat is being developed from within class resources, which has involved several imaginative fund-raising ventures. W M Nixon found himself being drawn into one of them.

It's official, The Cork Harbour National 18 Class are brilliantly capable of running a booze-up in a distillery. And just to make it even more challenging for their supportive members and many friends, they ran this particular fund-raiser for the new Phil Morrison boat in the Jameson Distillery in Midleton in East Cork on the first Saturday night of Lent.

Of course, like all Ireland on St Patrick's Day three weeks later, they got a special dispensation for the partying to continue unhindered by thoughts of Lenten piety. There was plenty of time for that next morning. But meanwhile, right there in the heritage and high tech splendour of the Midleton facility where tradition and new science are dynamically allied, the National 18 crews went at it good-oh, and the class's Development Fund was greatly enhanced.

In fact, I'm told the financial targets were comfortably exceeded, but as Class President Dom Long and the ever-energetic Tom Dwyer didn't tell us the targets in the first place, we'll happily take their word for it. All I know is that it was one helluva night, and only the National 18s could have done it.

Let's party! Colman Garvey's vintage National 18 welcomes guests to the Midleton Distillery for yet another event in a series of fund-raisers which have supported the development of the new boat from within class resources. Photo: W M Nixon

It's a class which – thanks to being a restricted design rather than a hidebound one-design – is able to wallow happily in its history as it thrusts towards new designs which keep up the spirits of its established sharpest sailors, while also encourage the vital new blood.

So how did it all come about? Well, thanks to a prodigious book written by Brian Wolfe of the boat's history, published in 2013 to mark the class's 75th Anniversary, we get some idea of the inevitable complexity of the story. The class started in 1938 in the Thames Estuary where there'd been several local one design or restricted "large dinghy" classes around the 18ft mark and soon – under a National Class imprimatur from the Yacht Racing Association – it spread to several other centres.

Needless to say, World War II from 1939 to 1945 brought any further growth and most sailing activity to a halt, but by 1947 things were looking up again, and in the straitened post war circumstances, the National 18 found its niche. Back in 1938, Yachting World magazine had sponsored a design to the class's rules by Uffa Fox, and that became the clinker-built Uffa Ace, which continued to be the backbone of the class for many years after the war.

It was Whitstable in the far east of Kent which produced most of the initial impetus for the class, and local builders Anderson, Rigden & Perkins made a speciality of it. In fact, ARP-built Uffa Aces were soon virtually the definitive National 18. Yet ironically we cannot confirm at the moment if the oldest National 18 still sailing – Richard Stirrup's 1938-vintage Tinkerbelle which races with the classics divison at Bosham SC on Chichester Harbour – is an ARP boat.

It's ironic because Tinkerbelle's first home port was Howth. It wasn't until I was writing the history of Howth YC for its Centenary twenty years ago that awareness surfaced that there'd been the nucleus of a National 18 class in Howth in 1938.

There were just three boats – John Masser's Wendy number 14, Tinkerbelle number 15, and Fergus O'Kelly & Pat Byrne's Setanta, number 16.

Tinkerbelle (15) being sailed by Aideen Stokes in 1939, with John Masser's Nat 18 Wendy (later Colleen II) astern, and the Corbett family's Essex OD Cinders abeam.

Tinkerbelle as she is today, the oldest National 18 still sailing. Her home port is Bosham on Chichester Harbour. Photo courtesy Richard Stirrup

Tinkerbelle seems to have been owned by a syndicate in which the Stokes family was much involved, though in the class history her earliest owner is listed as Bobby Mooney, son of the renowned Billy Mooney of Aideen fame. However, around Howth, Tinkerbelle was best remembered for being raced with considerable panache by a non-owner, Norman Wilkinson.

But when Norman returned from war service in 1946 determined to sail just as much as humanly possible, he found that the National 18s had faded away, and the only way he could get regular racing was by buying the 1898-built Howth 17 Leila, which he duly raced with frequent success right up to the end of his long life in 1998, by which time Leila was a hundred.

It's intriguing to think that, with one or two twists of fate in Howth, Norman Wilkinson might have been renowned as a star of the National 18s taking on the likes of class legends such as Somers Payne and Charlie Dwyer of Cork, where the class – having started with just two ARP boats in1939 - held fire for a while, but got going big time in the late 1940s and early '50s with several builders all round Cork Harbour creating them in local workshops.

That was one of the attractions of the National 18s. They were big enough to appeal to people who didn't fancy skittish little dinghies, yet they were small enough to be constructed by artisan boatbuilders who could produce lovely boats. But the owners – having laid out what were considerable sums of money at a time when Ireland seemed to be in a state of permanent economic depression – were disinclined to go the final stage of having the boats properly measured and registered with the class. This caused increasing problems, ultimately solved by a high level of diplomacy as the National 18s' popularity grew, and the opportunities arose for the Cork boats to go across the water to race in big-fleet competitions.

At one stage, class numbers were so healthy at many centres that in Britain they had Northern and Southern Championships, reflecting the primitive state of road movement of boats. Dinghy road trailers – particularly for hefty big 18-footers – were still in their infancy, so all sorts of ingenious methods were used to get boats to distant events, with a Whitstable boat on at least one occasion getting to Cork as deck cargo aboard a Coast Lines vessel on its regular route which took in Rochester in Kent and eventually Cork among several ports.

The National 18s in their classic prime, with immaculately vanished clinker-built hulls, and setting lovingly-cared-for cotton sails. Here, Crosshaven's greatest National 18 sailor Somers Payne (Melody, 206) is being pursued by Alan Wolfe in Stardust 63), while up ahead Charlie Dwyer with Mystic (208) is doing a horizon job, with the legendary Leo Flanagan of Skerries lying second at the helm of Fingal. The photo was taken during a Dinghy Week at Baltimore, and it is memories like this which inspired Brian Wolfe (son of Stardust's owner-skipper) to undertake the mammoth task of collating and writing the class's history.

In Ireland, centres which saw interest in the National 18s included Dunmore East, Clontarf and Portrush, but as Dun Laoghaire was committed to the 17ft Mermaid, the only place on the East Coast with really significant National 18s numbers was Skerries, where the incredible Leo Flanagan set the pace driving his Jensen Interceptor ashore, and racing his no-expenses-spared ARP-built National 18 Fingal afloat in somewhat erratic style.

Leo was a ferocious party animal, and when the Skerries and Crosshaven National 18s united in going to the big class championship at Barry in South Wales in the mid 1950s, Leo was very disappointed to discover that, just as the party was really getting going, the club barman had every intention of closing at closing time. The very idea....Leo solved the problem by buying the entire bar for cash on the spot.

As far as Leo was concerned, sailing was for parties, so when he heard of the highly-organised Irish Olympic campaign towards the 1960 Olympics in Rome, he got himself to Rome, as Olympic sailing promised Olympian parties. To his distress, he was ordered out of the Olympic Village by the Irish squad, who wanted no distractions. But to their distress, the bould Leo then turned up next morning for the first day's racing, officially accredited and highly visible in his new role – he had become manager of the Singapore team.

It seems that in a harbourside bar the night before, he'd met the helmsman of the Singapore Olympic Dragon (as it happened, the only Dragon in Singapore), who was racing in the Olympics as a personal venture. As the biggest rubber concessionaire in Malaya, he could well afford to do so. But this meant he was also Team Manager, and when Leo met him, the Singapore skipper was much upset, because with his sailing duties and need to get a good night's sleep before each day's racing, he was simply unable to take up all the official invitations which any Olympic Team Manager received.

He felt he was badly offending his hosts, and completely failing the Singapore sailing community So Leo, out of sheer kindness, agreed to be the Singapore Olympic Sailing Team Manager, giving selflessly of his time, energy and great wit in the front line at all the best and most fashionable parties throughout the 1960 Olympic Regatta.

All of which has little enough direct connection with the story of the National 18s, but it gives you some idea of the style of the people who have been involved in a long tale which will soon have been going on for eighty years. Yet beyond the parties and the many scrapes they got into, there was also much serious sailing and boat development going on, for although the Uffa Ace was the most numerous design in the growing fleet, anyone could have a go provided they fitted within the class rules.

But by the mid-1960s, it was clear that the traditional concept of a clinker-built National 18 was losing its appeal, and in 1968 the Class Association asked Ian Proctor to design a National 18 to be built as a smooth-hulled fibreglass series-produced boat, with bare hulls to be available for owners who wished to finish the boats themselves.

However, being mindful of keeping existing wooden boats competitive, the new boats were built much heavier than their glassfibre construction really required. Yet they looked good, and the first one Genevieve (266) was delivered to class stalwart Murray Vines, who sailed with the Tamesis Club on the Thames. There, the river may have been pretty, but it was so narrow that when the Tamesis people secured a major championship, they took their entire race management team down to the coast to attractive sea venues where the National 18s could do their thing with style and space.

That said, it was far from style and space they were reared. Murray Vines' son Jeremy – who is proud owner of the very first production version of the Phil Morrison Odyssey design which the class has been developing for the past two years – recalls his own earliest experience of championship competition with the National 18s in 1949 aged 11. He and his brother crewed for their father in 18/51 in a championship on the Medway in Kent, and they lived afloat on the boat, for in those days many National 18s lay to moorings.

Perhaps as a reward, the father built the two young Vines brothers their own International Cadet Dinghy the following winter. But Jeremy has remained loyal to the National 18 class to the point of being the pioneering owner for the new version of the design despite being at a certain age which you can work out yourself from that data given for the Medway in 1949. That said, he has given himself more space for his sailing as he has moved his base from Tamesis to Lymington, and in addition to the National 18, he cruises and races the Dufour 34 Pickle, a sister-ship of Neil Hegarty's award-winning Shelduck which featured in this column a week ago.

That the new wave of glassfibre 18s was not going to outclass the existing boats was forcefully demonstrated in 1970, when the class held its first combined all-British & Irish Championship in Cowes, after twenty years of separate Northern and Southern events. Despite the new glassfibre boats, the classics from Cork Harbour – where they'd been in the midst of celebrating the Quarter Millennium of the Royal Cork YC - were dominant, with Somers Payne right on top of his form sailing Melody (206) to win going away, notching only 1.5 points to second-placed clubmate Dougie Deane on 14.

Cork Harbour boats took the first six places in a crack fleet of thirty-one of all the best from every top National 18 centre, and the spirit of it all was best captured by the Thames Challenge Cup for a family crew going to Royal Cork's Dwyer family – Charlie and his sons Michael and a very young Tom – who placed sixth in Mystic.

The furthest flung fleet is at Findhorn in northeast Scotland, but the huge distance involved doesn't stop Royal Findhorn YC boats competing with the rest of the class. This is top RFYC helm Stuart Urquhart's Howlin Gael racing in the Solent, and every so often the class – including those from Cork – make the long trek to Finhorn for an annual championship.

However, in terms of championship success the movement towards overall victory by glassfibre boats had begun, and 1977 saw the last championship win by a wooden boat, with Mike Kneale's Maid Mary (183) from the Port St Mary fleet in the Isle of Man. This was a hotbed of National18 racing for a couple of decades, and after Mike had completely renovated the 23-year-old formerly only so-so Maid Mary, he clinched the 1977 title at Findhorn in northeast Scotland "just before you get to Norway", as I was told in Midleton last month. There, the Royal Findhorn YC is a byword for warm hospitality ashore and hot sport afloat, but despite a strong challenge by a formidable Cork contingent, the Manxmen won out.

But having done his duty by the classic wooden boats, for 1979 Mike Kneale and his team took a different tack – they commissioned a new National 18 design from ace ideas man Jonathan Hudson, which they composite-built around Airex foam whose use other Manx DIY boat builders such as Nick Keig had been deploying for long-distance multi-hulls.

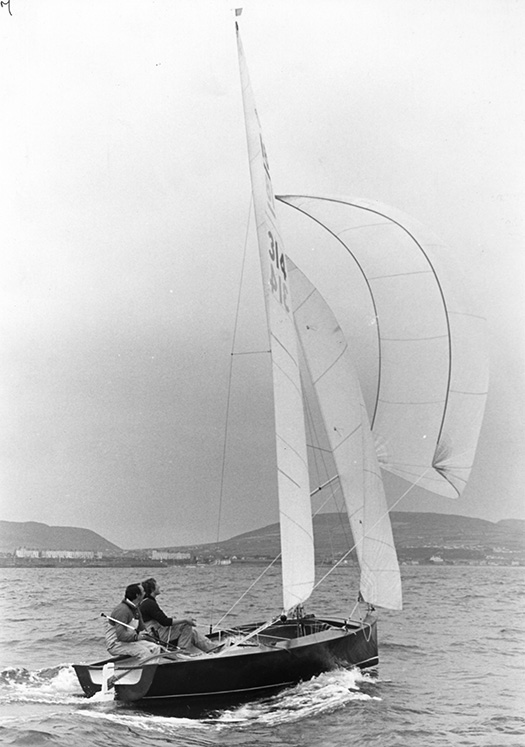

The Airex boat....Mike Kneale's innovative Woodstock on trials off Port St Mary in the Isle of Man in 1979.

Woodstock from the Isle of Man sails back into Crosshaven in 1979 with all the look of a boat which has just won the championship.

Despite – or maybe because of – her composite materials, the new boat was called Woodstock. And as Brian Wolfe's history of the class recalls, when she appeared for the well-supported 1979 championship in Crosshaven, "there was much debate", not un-related to the fact that Mike and his crew of Rick Tomlinson and Ross Thomas swept the board, taking the championship for Mike's fourth time in a clean sweep with the top boat from the home Cork Harbour fleet being Albert Muckley's Eastern Promise (323) in second overall for East Ferry SC.

So where was Somers Payne? Well, after dominating the national championship leaderboards since 1958 with the wooden Melody, in 1979 Somers was making his first foray into campaigning a glassfibre boat, and while he may have been third, the writing was on the wall, and the class was moving to class.

And there was new life at Royal Cork. The Royal Cork YC's National 18s were having one of their periodic re-births, and while Woodstock may have won the title, her designer reckoned it was only by extra skill that they stayed ahead of a new wave of young talents whose helming skills had been honed in events like the Admiral's Cup and many national and international championships in all sorts of boats. Their zest for international competition was buoyed up by the knowledge that, back home in Crosser, they had ready-to-go racing in the National 18s which was not only great sport, but somehow much more fun than sailing in other boats.

This continued level of enthusiasm at all ages meant that when the National 18 pace showed any signs of slackening, the Cork Harbour division could be relied on to get things up and moving again. Thus when the changeover to glassfibre had become complete at the front of the fleet, with many other owners happy to race their vintage boats in a classics division, some of the Corkmen questioned why new glasfibre boats were still being built overweight in order not to out-perform boats which now saw themselves as a different part of the class in any case.

The National 18 fleet in Cork Harbour was mustering serious numbers with the lighter GRP boats from O'Sullivan's of Tralee. Photo: Bob Bateman

So the Crosshaven people got the moulds from England, and encouraged the moving of them to O'Sullivan's Marine in Tralee (incidentlally just about as far west on land as you can get from Whitstable in Kent), where they were used to build a whole new wave of lighter boats which became the National 18 class as most of us have known it until this year. Now, the new moves into the Phil Morrison boat are providing a fresh direction for a class which nevertheless takes careful steps to ensure that older boats have their place in the sun with a chance of realistic racing against similar craft.

Although Jeremy Vines of Tamesis and Lymington is the owner of the first of the new boats (she's number 401, and is called Hurricane in honour of the very first National 18 built by Anderson, Rigden and perkins in Whitstable in 1938), he is untinting in his praise for the energy and vision of the Cork harbour division of the class in having the idea and then promoting the new Phil Morrison boat, and he makes a particular point of applauding the very tangible support which has been given to the project by the Royal Cork Yacht Club.

Into the blue.....Hurricane (number 406) is unveiled a fortnight ago at the Dinghy Show.

It's almost unfair, in such a community-based grass roots project, to single out anyone for special praise, but I got the feeling that folk like Colin Chapman, Dom Long and Tom Dwyer have been right there in the thick of it from the beginning.

The prototype having been tested and approved every which way, the moulds were made and the first dark blue hull emerged early in the New Year in one of the workshops which Rob White runs at White Formula Boats at Brightlingsea in Essex. So having been built at Tralee on the shores of the Atlantic for more than a decade, National 18 production is now back on the shores of the North Sea, but the spirit of the class at every location, regardless of where it might be, seems keener than ever.

The first of the new boats - of which sixteen have now been ordered – was Jeremy Vines' Hurricane, number 406, which was unveiled at the recent Dinghy Show in London. For a new generation which has been raised on the Phil Morrison-designed RS 200, this latest variant on the continuing National 18 story will speak volumes, and with eloquence. But it says everything about the spirit of this exceptional class that she rings a bell with seasoned National 18 sailors too.

The gang's all here. The new boat celebrated at the Dinghy Show with a group including many of those actively involved in its development, notably Colin Chapman, Tom Dwyer, Dom Long and Jeremy Vines.

The movers and shakers are (left to right) Tom Dwyer of the Cork Harbour National 18s, designer Phil Morrison, Cork Harbour Class President Dom Long, Jeremy Vines (owner of the first boat to the new Morrison design), and Rob White of White Formula Boats

Production Begins On New Design National 18 After Class Approval

#National18 - The National 18 Class Association has selected White Formula in Essex as its exclusive build partner for production of the new design National 18.

Over the summer, the class voted overwhelmingly to approve the 2013 design by Phil Morrison, a prototype of which took to the water in the Royal Cork Autumn League a year ago.

Construction of the first 12 ordered boats is now under way, with a view to finishing the class moulds by the end of this year to see the first vessels launching in time for the 2015 season.

The National 18 class website has much more on the story HERE.