Displaying items by tag: W M Nixon

Irish Cruising Club To Mark Centenary of Conor O'Brien's Circumnavigation at Sligo Dinner This Weekend

The Irish Cruising Club (ICC) gathers in County Sligo for its annual dinner this weekend, at which Commodore Dave Beattie will launch a new edition of Conor O'Brien's 'Across Three Oceans' to mark the centenary of the circumnavigation.

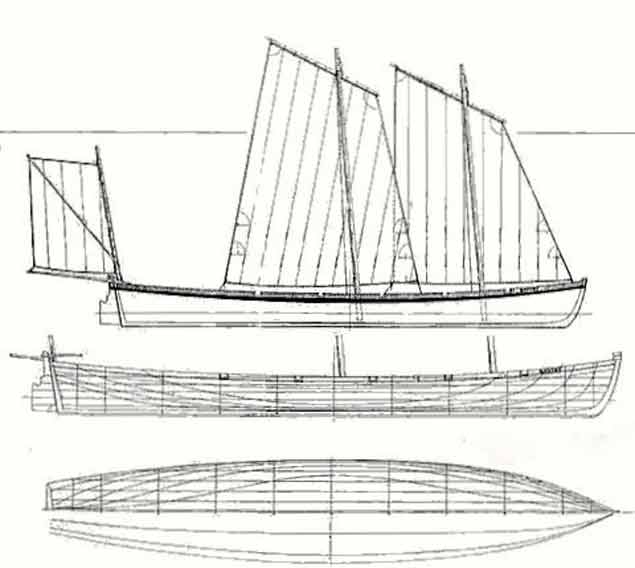

As Afloat reported previously, The new Irish Cruising Club/Royal Cruising Club book is the sixth edition of O’Brien’s pioneering account of his global circumnavigation south of the Great Capes with the 42ft Baltimore-built traditional gaff ketch Saoirse in 1923-1925. Compiled by Alex Blackwell and a special ICC/RCC Publications Committee, it includes extra material about O’Brien’s personal background and other after-thoughts on ocean sailing, which he added with additional analysis and further sea-going experience.

A new edition of Conor O'Brien's 'Across Three Oceans' marks the centenary of the circumnavigation and will be launched at the ICC dinner in Sligo

A new edition of Conor O'Brien's 'Across Three Oceans' marks the centenary of the circumnavigation and will be launched at the ICC dinner in Sligo

Fastnet Award

The ICC Dinner will also see the presentation to W M Nixon, of this parish, with the club's premier trophy for his 'exceptional achievements and for excellence in or closely related to cruising under sail'.

The Fastnet Award is a perpetual trophy that is not awarded every year, and Sligo will be the ninth occasion on which it has been presented.

Previous recipients include Paddy Barry and Jarlath Cunnane (inaugural Award, 2005), Robin Knox-Johnston, Commander Bill King, Killian Bushe and, in 2020, the Royal Cork Yacht Club.

The Fastnet Award is made for exceptional achievements and for excellence in or closely related to cruising under sail. This year it is made to W. M. (Winkie) Nixon who has been described by the late Theo Rye in Classic Boat magazine as “the doyen of yachting correspondents”. Rye has also written in reference to the whereabouts of a once famous yacht that if “Winkie doesn’t know, then nobody does”.

W M Nixon’s childhood was in a boisterous sailing family – he’d five siblings - living in a large and tall house built in several not necessarily harmonious architectural styles, and set in five acres on the shores of Ballyholme Bay to the eastward of Bangor on the south side of Belfast Lough. Despite its massive construction, the building’s upper storeys shook in severe nor’east gales in winter. But it was a young sailor’s paradise in summer, and with his father and uncle each owning a boat of the local Waverley Class, and then going into partnership as founder members of the Royal Ulster YC’s Alfred Mylne-designed No 1 Class (better known as the Glen Class) in 1948, he was seldom out of boats.

At the age of nine, he became the owner of a new 14ft Ballyholme Insect Class dinghy as the result of winning some family swimming competition. By 1957, aged 15, he was making his first cruise with this little boat Grasshopper and a tent, down the sailable length of the Upper River Bann from Portadown and across Lough Neagh, then down the Lower Bann to a conclusion in tidal waters at Coleraine, as his parents’ only stipulation was that he and his crew of one did not attempt to sail back to Ballyholme via the Atlantic coast and the North Channel.

The Ballyholme 14ft Insect Class Grasshopper was a multi-purpose, multi-people vessel used for racing, messing about, and cruising. Photo: W M Nixon

The Ballyholme 14ft Insect Class Grasshopper was a multi-purpose, multi-people vessel used for racing, messing about, and cruising. Photo: W M Nixon

At the end of the 1957 season, Grasshopper was sold, and he and his brother James moved on to the 26ft Swallow class, which was growing at RUYC, a boat somewhat like a small Dragon which - despite its design attribution to powerboat constructor and shipbuilder Tom Thorneycroft – is now known to be a creation of his Chief Draftsman, O’Brien Kennedy. With the Swallows, racing for trophies and winning more than a few was dominant, but there was an element of distance sailing with visits to the Strangford Narrows regattas involving a 25-mile coastal passage.

At Bangor Grammar School - on whose premises he spent the absolute minimum of time - his few contributions to the school magazine were about sailing, and by 1960 and now in college, he’d had his first item of paid-for sailing journalism published in Yachting World. 1960 also saw his first keelboat cruise, to the Clyde with future ICC members Ed Wheeler and Pete Adams together with others aboard the 9-ton 1912-built yawl Ainmara. She was chartered for a very modest sum from Belfast Lough’s “sailing angel” Billy Doherty, and the venture saw The Yachtsman added to his revenue-generating print outlets.

Billy Doherty, Belfast Lough’s “sailing Angel” for young would-be cruising folk, aboard his beloved Ainmara. Photo: W M Nixon

Billy Doherty, Belfast Lough’s “sailing Angel” for young would-be cruising folk, aboard his beloved Ainmara. Photo: W M Nixon

He’d been at Queen’s University Belfast, reading for an Honours Arts Degree in Psychology in a very leisurely four-year course, since 1958. As he was meant to be in Liverpool University studying architecture, it was a telling illustration of the cock-ups of which the exam-obsessed Northern Ireland education system was effortlessly capable.

He had done unusually well in exams in unexpected subjects in the Senior Certificate to facilitate his exit from school just as quickly as possible, yet despite everything and everyone pointing to him doing Honours History at Queen’s rather than Architecture in Liverpool – which was now eliminated from the options - he ended up in the relaxing backwater of the Psychology Department in QUB, ineligible for Honours History thanks to Latin having been dropped at school in order to streamline his progress through a shortened force-feeding education system, cunningly devised for a select few by the clearly certifiable headmaster at BGS.

Ultimately this was all to the good, as it honed his exam skills to such an extent that he emerged with a useful 2:1 despite only working for about a week each time exams came round. As for Liverpool, the very idea of having been there is now unthinkable, for in Belfast most of his interest and energy was taken up in the entertaining QUB Sailing Club with such people as Colm MacLaverty, Mick Clarke, Ed Wheeler, Mike Balmforth and Maurice Butler, with any other time being devoted to the social and external education possibilities more readily available in Belfast than Bangor.

The 23ft Skal was restored from near dereliction, and cruised single-handed in southwest Scotland in 1961. The mainboom has been raised to permit the 6ft pram dinghy to be carried on the coachroof.

The 23ft Skal was restored from near dereliction, and cruised single-handed in southwest Scotland in 1961. The mainboom has been raised to permit the 6ft pram dinghy to be carried on the coachroof.

On the cruising front, in 1961, he bought a semi-derelict 23-footer sloop called Skal, and restored her in record time to undertake a single-handed cruise in southwest Scotland before selling her to a determined purchaser in Helensburgh on the Clyde. It eventually resulted in a three-parter story in The Yachtsman. This fit-out and cruise had initially seemed a reasonably profitable venture, but by the time the outstanding bills were settled back at Tedford’s, the 19th Century-style ship and yacht chandlers on the quays in Belfast, there was little enough left, and it was all – and more - in the hands of the publicans of Belfast and Bangor by Christmas.

Suitably chastened, in 1962, he crewed with Dublin Bay’s Peter Odlum (met as a result of university racing in Dun Laoghaire) in his 8 Metre Cruiser/Racer Namhara in Clyde Week, and then hitch-hiked to the Hamble for a delivery cruise to Carrickfergus with the 52ft 1898-built former Ramsgate trawler Armorel which, though he wasn’t aware of it at the time, confirmed his seagoing credentials for ICC membership with sufficient power to overcome any social and personality drawbacks, while also providing more material for merchandisable maritime verbiage.

The former Ramsgate trawler Armorel provided some very varied seagoing experience in 1962. Photo: Mike Balmforth

The former Ramsgate trawler Armorel provided some very varied seagoing experience in 1962. Photo: Mike Balmforth

In 1962 he also competed the first RUYC Ailsa Craig Race in the totally characterful gaff cutter Marie Michon, resulting in his first sale of words to an American magazine, and he broke into Yachting Monthly with an article about cruising in West Scotland with Ed Wheeler on the latter’s uncle’s former Belfast Lough Star class Corona of 1901 vintage.

Meanwhile, he and Mike Balmforth found themselves on the Editorial Committee for the new magazine Irish Yachting, making 1962 a year with a certain Dun Laoghaire emphasis, for thanks to Cass Smullen and Paul Johnston, he was one of a group of university sailors invited to race the Dublin Bay 21s for their last season in their original jackyard topsail rig, as they started to change to Bermudan rig in 1963. There are very few sailors with such a specific and historic experience still left.

1963 was a special year, as he’d become a member of the Irish Cruising Club at the age of 20 thanks to northern committee member Darty Glover, who in addition to being Vice Commodore RUYC, was a lecturer and physiology researcher at Queen’s. Darty also nobly undertook the supposedly honorary role of Commodore of QUBSC, which was anything but honorary as he was often the only adult in the room, and sometimes had to go bail for an increasingly boisterous and expanding membership in what was Nixon’s final year as Captain. He left on a high, leading the QUBSC Team that finally won the Elwood Salver for an annual team race in Dun Laoghaire against TCD, which TCD had - until 1963 – won and retained continuously since it was inaugurated in the early 1930s.

Athletes at the ready. Ed Wheeler and W M Nixon waiting to race for Queens University against Trinity Dublin in the Elwood Salver of 1963 – which they won for the first time since its inauguration in the early 1930s.

Athletes at the ready. Ed Wheeler and W M Nixon waiting to race for Queens University against Trinity Dublin in the Elwood Salver of 1963 – which they won for the first time since its inauguration in the early 1930s.

Now working in Belfast and married for the first time (his daughter Patricia and her husband Davy Jones of Howth are both ICC members) he saw the three seasons of 1963 to 1965 with annual fortnightly cruises in Ainmara with Ed Wheeler and the late Russell O’Neill, both of whom were to become ICC members.

1963 was to the Outer Hebrides, 1964 round Ireland without an engine, thereby accidentally establishing a speed record which stood for some time, and in 1965 they went to St Kilda, where a suddenly approaching low of “972 and deepening” bound for the Hebrides would have made for an interesting time in Village Bay if it had passed to the south of the island, but it zoomed past close to the north.

Ainmara (left) in Village Bay, St Kilda, in June 1965 the morning after a deepening Low of 972 had passed close to the north. Photo: W M Nixon

Ainmara (left) in Village Bay, St Kilda, in June 1965 the morning after a deepening Low of 972 had passed close to the north. Photo: W M Nixon

All of these cruises were awarded the ICC’s Fortnight Cup and duly written up for The Yachtsman, and meanwhile, in 1964 before cruising round Ireland, he was persuaded by Darty Glover to charter Ainmara for the annual Round Isle of Man Race – then the numerically largest offshore event in the Irish Sea. With his brother James (a TCD medical student who became Irish Helmsman’s Champion in 1965) and two others as crew, the overall win was pulled off through some glorious flukes, resulting in another article snapped up by Boating of New York, and a report for Irish Yachting with which his involvement was expanding, while Yachts & Yachting was also taking regular offshore racing stories and he was now also Irish Correspondent for the popular Around the Coast section in Yachting Monthly.

1966 saw a detailed cruise in Ainmara with Pete Adams ICC to West Cork – a different place in those days – and much North Channel offshore racing (sometimes including Scottish ports) while later sailing as a member of the RUYC crew that delivered the 66ft Royal yawl Bloodhound from Belfast to Gosport - all of it grist to the mill of sailing stories through outlets on both sides of the Atlantic.

Ainmara in Glandore, June 1966 Photo: W M Nixon

Ainmara in Glandore, June 1966 Photo: W M Nixon

Having found that he was still too young for domesticity, he returned to singleton status, but what looked like being the footloose and fancy-free season of 1967 took on a real purpose with short-notice involvement in a cruise to Iceland from Portstewart on Ireland’s North Coast with the 25ft Vertue Class cutter Icebird.

Basically, it was a mountaineering venture to the Myrdalsjokul icefield in the middle of Iceland, with little Icebird as the expedition ship and Nixon as the nautical input. As they departed northward in late May after a very hasty fit-out, the season was early for high-latitude North Atlantic voyaging, so they were treated to a gale or two of winter ferocity on an eight-day passage. But it was all character-building for the up-country experiences, for with the location-delivery “Expedition Vehicle” being an ordinary Volkswagen Beetle rented in Reykjavik, Nixon found himself alone, driving back across the unmade roads in a vast landscape and gathering dusk, incurring the inevitable punctures with such regularity that he was forced to make the welcome discovery that each utterly isolated farmstead was well equipped with effective puncture repair kits, and generous in their use.

He flew back in an ancient Dakota for a month in Ireland and some offshore racing and a little work, and returned on the first flight with Loftleidir’s pride-and-joy, a brand new Boeing jetliner, to find the mountaineers were still just about talking to each other, but it was with a changed ship’s company that he hoped to sail northabout around Iceland before heading for home. However, persistent gale force-plus headwinds and the boat’s limited windward ability under her original cotton sails put paid to that, yet even so it was still fourteen days out of Reykjavik and long in an engine-less condition when they finally came in through Vatersay Sound to Castlebay on Barra in the Outer Hebrides and a great feasting on newly-bought fresh oranges, followed by an Icebird-redeeming fast reach over the final hundred miles back to Portstewart.

The Vertue Class 25ft cutter Icebird off Portstewart on her return from Iceland – she still set her original 1953 cotton sails. Photo: W M Nixon

The Vertue Class 25ft cutter Icebird off Portstewart on her return from Iceland – she still set her original 1953 cotton sails. Photo: W M Nixon

As neither the owner nor his nephew (the co-leader of the Icelandic mountaineering expedition) had the time availability to do anything with Icebird, Nixon had the loan of her for two or three years, and secured a winter berth in the big shed at Erskine’s characterful boatyard in Whitehouse on the shores of the seemingly remote territory of north Belfast. She was in the shed alongside Ainmara, now owned by Dickie Gomes after Billy Doherty’s death in 1966.

First met in the Skal year of 1961, Dickie had become a firm friend and fellow ICC member with many miles already logged and many more – some in extraordinary craft – still to be sailed, so the crack in Erskine’s shed was good as Nixon had been joined by Ed Wheeler to give Icebird a complete makeover and replacement sails in order to voyage south the following summer, and simply continue sailing south.

Two boats which figure prominently in the story – Ainmara and the Hustler 30 Turtle in Strangford Lough in 1984.

Two boats which figure prominently in the story – Ainmara and the Hustler 30 Turtle in Strangford Lough in 1984.

But that grand plan was blown asunder in April 1968 when Nixon had a coup de foudre on meeting Georgina Campbell for the first time in a bar in Belfast’s university district while supposedly homeward bound from boat work. By the time the transformed Icebird was afloat, “simply sailing south” had been edited back to cruising northern Spain. It was all being done on a shoestring, but in Coruna they met with mysterious characters who suggested to Ed that crewing positions were available across the harbour on a rusty Liberty Ship that was being delivered – “smuggled” was perhaps a more appropriate term - out to very Communist China for scrap, and they said it was easy money for old rope, with an interesting visit to the Far East and anywhere else he fancied thrown into the bargain.

Ed got himself signed on to join in a fortnight, so the duo cruised Icebird eastward with much enjoyment along Spain’s often spectacular North Coast, and parted company in San Sebastian for Ed to return to Coruna to join ship, while Nixon made his way back to Ireland single-handed with a fortnight’s agreeable coastal cruising in south Brittany, and a visit to Cornwall to see Georgina at home at her parents’ house and continue to plight his troth, followed by a somewhat rugged upwind passage to Kinsale in very unsettled weather.

Meanwhile Ed’s supposedly easy ship’s passage of a few weeks from Coruna to China became many months of total nightmare, but it has recently resulted in a hugely entertaining lockdown-created article in the The Marine Quarterly. And for Icebird and Nixon, as with the Iceland cruise the Spanish jaunt provided further material for selling published stories on both sides of the Atlantic, while the return to Northern Ireland revealed that an idea first aired in 1964 had returned with renewed vigour.

During that successful Round Isle of Man Race of 1964, one of the crew aboard Dick & Billy Brown’s Black Soo from Portaferry as she chased Ainmara round the island was Ronnie Wayte, an inventive bundle of energy who had a multi-purpose factory in Carrickmacross in County Monaghan where, with his newfound enthusiasm for offshore racing, he decided to build a Fastnet Race contender. And after Ainmara’s freak win, he’d decided that Nixon was the man to do it with him and his team, with the 1969 Fastnet Race in mind.

The factory was in Carrickmacross because, as a Border County, Monaghan was eligible for all sorts of industrial grants, and as Carrickmacross was the nearest town to Dublin, it was heaving with new or re-purposed factories where all sorts of crazy ideas were being pursued. Nevertheless a 35ft offshore racer from scratch was crazier than most, particularly as the ramifications of running a business venture on the very edge of viability meant that work didn’t start until April 23rd. Yes - April 23rd 1969. Yet somehow – with the booster of having won an offshore race in the Irish Sea - Mayro of Skerries was on the start line in Cowes on August 8th 1969 for the RORC Fastnet Race, and finished 122nd overall out of 256.

“It took a helluva lot of boats to beat her”. The 35ft Mayro of Skerries – built in three months from scratch in Carrickmacross in County Monaghan – placed 122nd out of 256 finishers in the 1969 Fastnet Race

“It took a helluva lot of boats to beat her”. The 35ft Mayro of Skerries – built in three months from scratch in Carrickmacross in County Monaghan – placed 122nd out of 256 finishers in the 1969 Fastnet Race

Although considerable comfort could be drawn from the supposed quality of some of the boats behind her, Ronnie Wayte subsequently developed a more sensible approach to boat procurement. But in going through various Skerries ownerships, Mayro was eventually wrecked in the beach in that exposed anchorage. Yet a bit of her will probably survive for ever – when her original Carrickmacross-made fibreglass mast proved to be too flexible, it was replaced in jig time by an expertly-made alloy mast, but happily the fibreglass mast proved more than sufficiently robust to be the new Skerries Sailing Club flagstaff, and it’s still there.

Nixon did well out of it, as his account of the Mayro story was to go viral or whatever was its printed 1969 equivalent in America, and he sailed her home to Ireland with the happy thought that post-race in the bar of the Royal Western in Plymouth, a fellow-member of the occasionally-meeting Irish Yachting Editorial Committee, cartoonist Bob Fannin, revealed that money made from the sale of the News of the World Sunday newspaper in London to Canadian mogul Roy Thompson was set to flood into Dublin to finance a new comprehensive publishing group, and they were thinking of including Irish Yachting in their proposed stable of consumer magazines, with Nixon as the Editor.

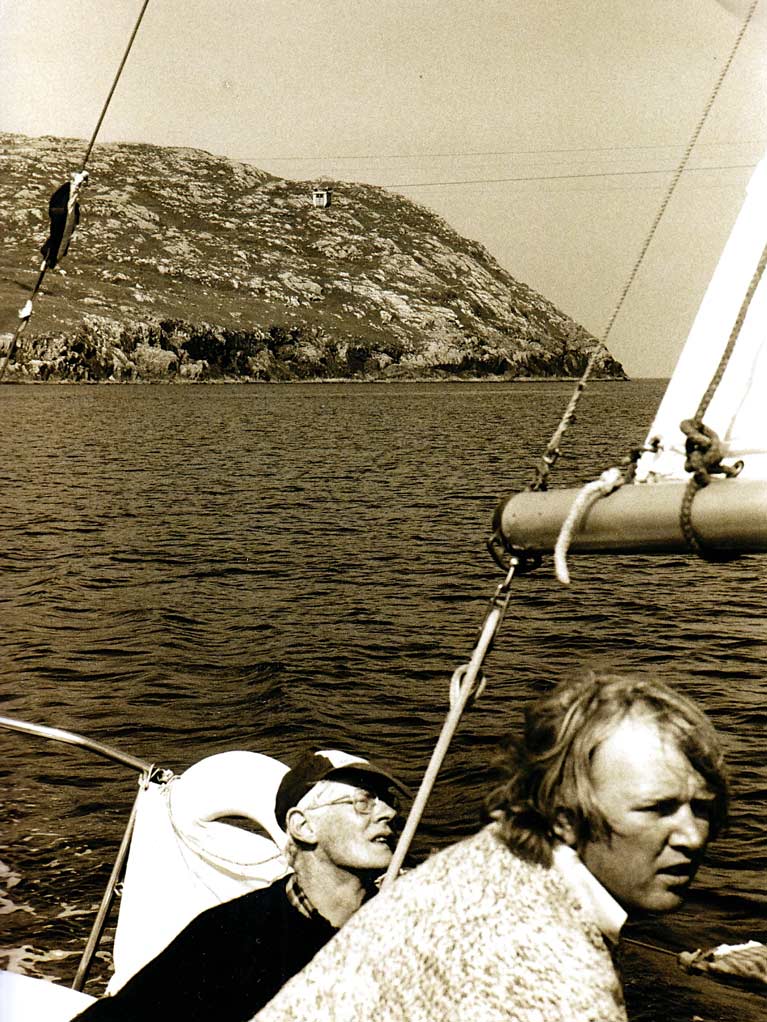

“Whatever next?” Nixon homeward bound post-Fastnet aboard Mayro in August 1969, after hearing (over a drink) that he might be in line to be the Editor of a fully-financed Irish Yachting.

“Whatever next?” Nixon homeward bound post-Fastnet aboard Mayro in August 1969, after hearing (over a drink) that he might be in line to be the Editor of a fully-financed Irish Yachting.

And so it came to pass that by early 1970 he and Georgina were set up in Dublin with herself doing a post-Grad at Trinity and subsequently teaching, while he found himself with a brand new Ford Capri company car, yet still working as a free-lance as was the practice among many of the journalists in that short-lived but mightily entertaining enterprise.

Home was a flat in Baggot Street, right at the Patrick Kavanagh-haunted heart of a city that was coming pleasantly to improved economic life without being obnoxiously busy and noisy. They could usually find legal parking for the much-travelled car right outside the front door, while the flat included a working telephone whose bill was apparently being paid by the H Williams Supermarket on the corner, yet it was impossible to convince An Post that this was so, even while they continued to use the phone at no cost to themselves

The local hospitality establishments were in a golden mile from the Intercontinental in Ballsbridge to the Horseshoe Bar in the Shelbourne, and the handiest - the unbelievably rural Toner’s - was right next door. On the water, the sailing calendar was busier than ever, with the policy of continuing to sail as much as possible, while also writing about it in an increasing number of outlets - between hectic monthly bursts of magazine editing - continued on an upward curve. 1970 included being left in Cork for the Royal Cork Yacht Club Quarter Millenial Regatta Week with a Swan 36 which he’d helped race from Belfast Lough in the main offshore event, with the owner – before he rushed home - stipulating only that the boat be back in Donaghadee within a fortnight.

That first Cork Week of 1970 was just a 30-boat affair with racing on only three days, but Francis Chichester was in town for the completion of his new Gypsy Moth V in Denis Doyle’s Crosshaven Boatyard, and in the absence of Lady Sheila he was having the time of his life in presiding at the daily prize-givings, with the week ending well for the absent owner’s Swan 36 with the overall win – raced with a minimal family crew - in the concluding Crosshaven-Kinsale race, resulting in the careful shipboard conveyance of an enormous Waterford crystal rose-bowl back to Donaghadee.

The Hustler 35 Setanta now has Dun Laoghaire as her home port

The Hustler 35 Setanta now has Dun Laoghaire as her home port

There was involvement too in the Northwest Offshore Racing Association events out of Dun Laoghaire and Howth across to Wales, and in 1971 these acquired extra significance as they were used for training in Ronnie Wayte’s sensible new boat, the Holman & Pye Hustler 35 Setanta of Skerries, which seemed to provide marginally better all-round performance than the S&S 34s in which the majority of Irish Cruising Club offshore racers competed. For in those days, offshore racing was an integral part of ICC activity, such that in 1975-78, having been RORC Rear Commodore in 1972-75, the great Denis Doyle was ICC Commodore, and was famous for putting through the AGMs, complete with the distribution of the then-admittedly-much-smaller selection of trophies, in just 25 minutes flat.

In due course it was time to grow up and move from Baggotonian Bohemianism out to a new house being built in a handy small development one street back from the waterfront in Howth, where Nixon had been a Howth YC member since 1969. This happened in the Setanta year of 1971, on the day that the great Jack Kelly-Rogers was on the tarmac at Dublin Airport to lead the welcome for the new Aer Lingus Jumbo Jets, and as the entire move out to Howth was made with the company Ford Capri in three journeys with all their goods and chattels on the roof-rack, RTE’s afternoon-long broadcast of the big event out at the airport on the car radio is part of the memory.

With an extraordinary crew of all the talents, Setanta had a good year, with her overall class win in the NWOA Championship secured before she’d even left for the Solent, where performance in Cowes Week improved such that in the Fastnet Race itself, they burned off all the S&S 34s to finish second in Class IV, beaten only by Alan Bourdon’s ready-planing Pionier 10.

1971’s mainstream sailing concluded for Nixon with a meeting of the great and the good in Howth after the Abersoch race to begin turning the NWOA into ISORA. With that concluded and followed by a decade of regular ISORA racing, 1972 was a “settling into living in Howth” year, with an able little Galion 22 which was family-cruised to West Cork. There, time was spent with Dermot Kennedy of Baltimore clearly enunciating his views as to what the proposed new Irish sail training vessel to replace Asgard should look like. When reported in Afloat Magazine (as Irish Yachting had been since March 1971) and read by new Minister for Defence Paddy Donegan ICC, the Kennedy Opinion resulted – eventually but directly – in the new Asgard II designed and built by ICC member Jack Tyrrell of Arklow.

On another tack, Nixon had started a weekly sailing column with the Irish Times at the suggestion of the then Quidnunc of The Irishman’s Diary, Seamus Kelly. This resulted in an offer by the paper to fund a three weeks on-site Nixon coverage of the up-coming 1972 Olympic Games Sailing Regatta in Kiel in which Ireland was putting forward a strong team. When the first report appeared, the Irish Independent and the Cork Examiner requested syndication which was duly provided, but for some reason these high-profile newspaper associations offended the amour propre of the already-floundering publishing group which had taken on what was now Afloat Magazine, so for a while Nixon was carrying the continuing publication of Afloat on his own, with sterling help from Georgina.

However, with demand increasing with a new regular vaguely cruising-oriented column for Yachting World which was meant to run for 12 months but ran unbroken for 25 years, Nixon was able to claim that he had to keep sailing despite new demands of additional fatherhood, and for that – being temporarily unable to afford a cruising boat of his own – he needed access to a craft large enough to accommodate what was in effect an office.

There was something of a Howth miracle in that Otto Glaser – whose time and energies were almost entirely taken up with developing his electronics company – was only able to give enough time to his new 47ft McGruer sloop Tritsch-Tratsch IV for flat-out racing in major events, particularly the RORC programme. In between, there were vast tracts of delivery logistics requirements, often along choice coastlines.

A symphony of exquisite woodwork – the 47ft McGruer sloop Tritsch-Tratsch II found her way to some very offbeat places between major races

A symphony of exquisite woodwork – the 47ft McGruer sloop Tritsch-Tratsch II found her way to some very offbeat places between major races

What was not to like? The Glaser-Nixon requirements intermeshed perfectly, and while Tritsch-Tratsch II was always there on the starting line as required, in between she could be found in activities as diverse as crossing the drying Tresco Flats in the Isles of Scilly at high water in order to follow the Friday night gig race, filling the pool at Restronguet as unofficial flagship for a Falmouth Sailing Workboat Regatta, or lying in style off some select Breton restaurant as the alternative crew – which always seemed to be larger than planned – enjoyed a leisurely seafood feast.

During time in the Hamble working with designer Rob Humphreys to get the big boat’s rating down a bit, Nixon met up with internationally-renowned cruising authors Eric and Susan Hiscock whose steel ketch Wanderer IV was having a makeover by Moody’s, and by 1978 this new friendship had resulted in membership of the Royal Cruising Club. Hiscock also encouraged Nixon to finish a book, The Sailing Cruiser, a comprehensive guide to modern cruisers, which was published in 1977 by Nautical in Europe, and did particularly well when re-published in America.

This in turn, led to the Irish Cruising Club commissioning a history of the ICC for its Golden Jubilee in 1979, and this – called To Sail The Crested Sea in a quote from the voyaging St Columba - came out in the nick of time for the huge Jubilee Cruise-in-Company.

However, Nixon was determined that nothing would get in the way of his own sailing, in which he aspired to lead a normal club sailor style of life, with local racing, an offshore programme with the occasional big one, and regular cruising with reasonably manageable longer ventures from time to time. All this was to be fitted in with developing family life in a house which lent itself so well to useful extensions that they still live in it.

But he had became slightly led astray by a deluded would-be entrepreneur in 1973, who claimed to have the resources to build a new Half Tonner, to be designed by Billy Brown to Nixon’s suggestions, and crafted by master shipwright Donal Conlon in his new purpose-built shed at Carnadoe on the Shannon in Roscommon.

The Billy Brown-designed Half Tonner Garland of Howth emerging from Donal Conlon’s shed at Carnadoe

The Billy Brown-designed Half Tonner Garland of Howth emerging from Donal Conlon’s shed at Carnadoe

Things seemed to go well at first, but it turned out the original begetter was without resources, so the two boyos had to continue on a wing and a prayer, and in the summer the handsome but empty-tanked Garland of Howth made something of an impact by winning Class B in the Captain’s Cup series at Holyhead and the South Rock Race in the north. But it was a great relief for bank managers and supportive colleagues alike when she was quickly sold to old friend Dickie Richardson, Chairman of ISORA.

Garland of Howth saiing in Strangford Lough after winning the South Rock Race – Dickie Gomes, James Nixon and Billy Brown in board

Garland of Howth saiing in Strangford Lough after winning the South Rock Race – Dickie Gomes, James Nixon and Billy Brown in board

The two seasons which followed with Tritsch Tratstch II were a balm in their way, but when sailing mate Johnny Roche took the Nixon advice and bought the South Coast OD Safina and invited our man to be a shipmate for a couple of seasons, it proved the perfect alternative to the surreal world of RORC Class I racing against the likes of Ted Turner. Rewarding cruises to North Wales in 1976 and the Outer Hebrides in 1977 were the result for the super little Safina, with well-illustrated articles on the Scottish islands proving irresistible to large-format Canadian sailing magazines.

Safina was a South Coast OD, the best 26-footer of her generation, offering remarkably good accommodation with an excellent all-round performance. Photo: W M Nixon

Safina was a South Coast OD, the best 26-footer of her generation, offering remarkably good accommodation with an excellent all-round performance. Photo: W M Nixon

However, owning a family boat was always the underlying ambition, and while the kids had an Optimist or two, and the family had a Mirror, by introducing the Squib class to Howth in 1979 Nixon had a boat which could be club raced, locally cruised, and most importantly, family sailed.

The new class thrived, but it only served to strengthen the desire for a genuine cruiser. After a false start in 1980 with a burnout-inducing renovation of a very worn Halcyon 27 which restored so well she sold almost immediately, our man found himself beside Tom Roche in a Leeson Street nightclub in the small hours. Knowing that the Nixon family already approved of Tom’s partnership-owned Hustler 30 Turtle which was known to be for sale, he made Tom an offer around 4 o’clock in the morning which was duly accepted, and ten very happy Turtle years ensued during the 1980s.

The Hustler 30 Turtle and the previously-owned Squib Huppatee which had started the Squib class at Howth

The Hustler 30 Turtle and the previously-owned Squib Huppatee which had started the Squib class at Howth

For though she was the shoal-draft version developed for the Royal Yorkshire Yacht Club’s drying berths in Bridlington, she never pretended to be anything she wasn’t – she was manageable yet commodious for family cruising, and in racing she could be a wolf in sheep’s clothing, winning the Lambay Race overall in 1981, the Skerries to Carlingford race in 1985 with hot Shamrocks in her wake, and several cruising club awards from both the ICC and the RCC, including the Round Ireland Cup twice, in 1982 and 1988.

Turtle in South Cove at Gola island in Donegal in 1982 during the cruise which saw her first award of the Round Ireland Cup. Photo: W M Nixon

Turtle in South Cove at Gola island in Donegal in 1982 during the cruise which saw her first award of the Round Ireland Cup. Photo: W M Nixon

“The best No 2 genoa in Howth” – Turtle sometimes surprised everyone – her crew included – with her racing performance, and in 1981 she was overall winner of the Lambay Race. Photo: Jamie Blandford

“The best No 2 genoa in Howth” – Turtle sometimes surprised everyone – her crew included – with her racing performance, and in 1981 she was overall winner of the Lambay Race. Photo: Jamie Blandford

However, she was not really a serious proposition for frontline offshore racing, and even though the ICC was veering away from involvement in the competitive game, Nixon was keener than ever to see if a genuine cruiser-racer was still possible – a boat in which you could really cruise carrying grown-up ground tackle and all comforts provided they could be kept out of the ends, yet also a boat which - with a very few special extra sails - could be realistically raced.

The chance came with the acquisition in 1990 – in partnership with Ed Wheeler and Harry Whelehan – of a Doug Peterson-designed Contessa 35 which sailed so impressively from Strangford Lough down to Howth at Hallowe’en 1990 that – as the previous owner wished to retain the name – she was retitled Witchcraft of Howth.

Paddy Goodbody and his boatyard team in Wicklow did the necessary work, the piece de resistance being the vertical self-stowing chain box beside the mast in which 45 fathoms of ideally-sized chain were to provide comfort in many a windy anchorage. The enormous tiller – awkwardly running the length of the cockpit, was replaced by full-size wheel steering, complete with elkhide covering – including the vital six inches on each spoke – made by Amy Mockler in Crosshaven.

“Effortless, steady speed” – Witchcraft of Howth in cruising mode in the 1996 ICC Cruise-in-Company to West Cork. Photo: Kevin Dwyer

“Effortless, steady speed” – Witchcraft of Howth in cruising mode in the 1996 ICC Cruise-in-Company to West Cork. Photo: Kevin Dwyer

Being such a powerful boat, all new equipment was specified for the 40-45ft range, while an Eberspacher heater with three outlets transformed the interior. She was and is such a versatile boat, cruising comfortably to places like St Kilda at a very good average speed, then coming into her own on the race-course as they got to know her. A particular peak was reached in 1993 when she was awarded the Strangford Cup of the ICC and the Founder’s Cup of the RCC for a two-week cruise to the Faroes and the Hebrides in a season which also included winning the Howth-Bangor Race and the RORC/ISORA end-of season race, followed by success in her class in the Autumn League in Howth.

“Rewarding to race” – Witchcraft in action at ISORA Week in Howth

“Rewarding to race” – Witchcraft in action at ISORA Week in Howth

Two cruising club awards and an RORC win by one and the same boat was very satisfying, but 1995 was as good, with an early season three week cruise to Northwest Spain (she can make short work of crossing the Bay of Biscay), followed by second in class in the Dun Laoghaire-Dingle Race, continuing with a Round Ireland Cruise, and concluding on the podium in the Autumn League, with the ICC’s Fingal Cup and an RCC award to show for it all.

Inevitably Nixon was drawn into sailing administration, although the wild captaincy of QUBSC back in the early ’60s was not necessarily helpful training for the subtleties of adult committee work. Nevertheless he was on the Council of the Irish Yachting Association (which became the Irish Sailing Association while he was on it) from 1972 to 1983, and he served on the Offshore Committee from 1975 to 1983. He found himself on the Committee of the RCC from 1993 to 1998, organising Challenge Cup Commemoration events for Howard Sinclair’s Centenary in 1995 in RUYC, and Conor O’Brien’s 75th Anniversary in 1998, as a result of which the remarkable whalebone commemorative bust of O’Brien by Danny Osborne is on display in the Royal Irish YC.

Conor O’Brien as carved from the vertebra of a blue whale by Danny Osborne of Beara

Conor O’Brien as carved from the vertebra of a blue whale by Danny Osborne of Beara

The uniquely arduous task of adjudicating logs was fulfilled for the Cruising Association in London in 1982, and the RCC in 2011. Somehow in 1986 he also found the time to be on Robin Knox-Johnston’s Round Ireland Record setting crew in the 60ft catamaran British Airways, but he confesses to being unaware of the precise number of times that he has sailed round Ireland, as there have been three Round Ireland Races from Wicklow in there somewhere, two of with class placings.

Robin Knox-Johnston’s 60 catamaran British Airways departs Dublin Bay on a successful Round Ireland Record attempt in May 1986

Robin Knox-Johnston’s 60 catamaran British Airways departs Dublin Bay on a successful Round Ireland Record attempt in May 1986

In addition, he served on the Management Team for the Irish Admirals Cup Team in 1987 (the most successful of all, 4th out of 13 nations with the Dubois 40 Irish Independent overall Fastnet Race winner), and in 1998 he was on the Committee for the Tall Ships Visit to Dublin, in addition writing the book, Asgard: The Story of Irish Sail Training, with Captain Eric Healy.

Meanwhile in 1992 and 1994, Cork Week was contested with the crew living in the boat. With the well-furnished Royal Cork clubhouse and compound providing everything that one could reasonably wish from life, he wasn’t surprised to be told on the Friday evening by the Security Guard at the gate that his pass indicated that he hadn’t left the place before, nor indeed apparently entered it, as he’d arrived under sail.

Back in May 1994, it had also been the 30th anniversary of the Round Isle of Man win by Ainmara, so in ’94 they took Witchcraft over for a more mature visit to the island and a token start in that year’s Round IOM Race, but somehow the token participation just went on and on back to a token finish, and as it had been thirty years earlier with Ainmara, they’d hit a lucky streak, with the red boat doing the business.

In that same decade with the unstinting support of Ian Malcolm as “Materials Resourcer”, he wrote the award-winning Howth: A Centenary of Sailing, a real door-stopper with 550 illustrations which was published on Saturday November 18th 1995, the exact Centenary to the day of the foundation of Howth Sailing Club, with a monumental party in the still avant garde Howth Yacht Club clubhouse to mark the occasion with some chaos, as a certain genius had decided that drink should be sold at 1895 prices.

The home place – an attempt to celebrate the Centenary of Howth Yacht Club in 1995 with 1895 prices for the party had some very interesting results

The home place – an attempt to celebrate the Centenary of Howth Yacht Club in 1995 with 1895 prices for the party had some very interesting results

In all, Nixon has been involved in at least seven books including his Cruising & Voyaging Editor’s role in the Encyclopedia of Yachting, published 1989. And there are more in the pipeline. But it’s all in a changing world of rapidly evolving communication techniques, and our man is – to say the least – losing youthful agility.

The fortunately very delayed ill-effects of a childhood toboggan accident had begun to show, and the results of a comprehensive X-Ray programme in 1998 were not optimistic. Nevertheless after an operation or two, he was able to continue sailing and in 2003 Witchcraft and Nixon found themselves in the almost-impossible role of mothership to the 15 Howth 17s – several of them with close relatives on board – when they descended in the Glandore Classics, and created some mayhem along the West Cork coast. But at least the mothership – “always the last to know” – was rewarded with the ICC’s Fortnight Cup forty years after it had first gone to Ainmara.

The old yawl meanwhile was approaching her Centenary in 2012, for which Dickie Gomes – approaching his Golden Jubilee of ownership – gave her a major refit, and he and Nixon cruised her in the Centenary Year of 2012 to the Outer Hebrides, for which they jointly were awarded the Fingal Cup while Nixon’s account of this idyllic cruise featured in Yachting Monthly.

The following year saw the Golden Jubilee of the Old Gaffers Association with one of the main gatherings at Ringsend in Dublin, Ainmara’s birthplace, so they brought her south to contest the inaugural race for the DBOGA Leinster Plate and duly won it, and also won the main award at the Traditional Boat Festival in the Isle of Man.

Then in 2016, the 150th Anniversary of Royal Ulster YC came up on the agenda, and the team re-assembled to take Ainmara around the jumps off Bangor for the Parade of Sail, getting the “Boat of the Show” award for what was in effect The Last Hurrah, as Ainmara was on the market and soon went to new Swiss owners.

The Last Hurrah for Ainmara in Belfast Lough as she heads for the “Boat of the Show” award in the RUYC 150th Anniversary Regatta with Dickie Gomes on the bowsprit and Winkie Nixon at the helm

The Last Hurrah for Ainmara in Belfast Lough as she heads for the “Boat of the Show” award in the RUYC 150th Anniversary Regatta with Dickie Gomes on the bowsprit and Winkie Nixon at the helm

Ironically, 1998 – the “Year of the Big X-Ray” – had also been the year in which Commodore Bob Drew saw to it that Nixon became a member of the Cruising Club of America to whose journal he was to make several contributions, as he had to Yachting and WoodenBoat in America, and to Chasse Maree in France and Boot in Germany, while still figuring in longer publishing relationships, with Yachting World celebrating his 50 years involvement with them by featuring a three-parter on the wonderful 48ft sloop Carina CCA of Richard Nye and Jim McCurdy associations.

And of course the continuing symbiotic relationship with Afloat.ie is in the very air he breathes, together with a worldwide readership. However, with the Internet taking over everything, it has to be acknowledged there were good things in the good old days. In the time of print, a harassed journalist with nine regular outlets tended to think nervously of deadlines. But in the 24/7 world of today’s systems, we now realise that deadlines were actually lifelines. Once you’d sent off the hard copy – the only copy – that was it, the job was done, and you could plan an unhassled weekend on the boat.

But now, it’s an open-ended continuous demand. Or it would be, if you let it. But somehow even with all sorts of electronics trying to alter our perceptions afloat, sailing continues to be one of the most wonderful things in the world.

The Fastnet Award of the Irish Cruising Club

The Irish Cruising Club comprises a group of people dedicated to promoting cruising under sail around the Irish coast. It publishes sailing directions for the Irish coast in two volumes – North & East and South & West Coasts. These are kept regularly updated and are the leading publications of their kind dealing with the Irish coastline. They are used by yachtsmen, the rescue services, Irish Lights, the Naval Service, the Royal Navy and by fishermen and commercial operators.

As part of its activities, the ICC presents awards that recognise achievements related to its central mission. The premier award, the Fastnet Award, is a perpetual trophy which is presented not more often than annually, but it is not anticipated that it will be awarded every year. This will be the ninth occasion on which it has been presented. Previous recipients include Paddy Barry & Jarlath Cunnane (inaugural award, 2005), Robin Knox-Johnston, Commander Bill King, Killian Bushe and, in 2020, the Royal Cork Yacht Club.

It's first blood to Kaya, Frank Whelan's J/122 from Greystones Sailing Club after a closely fought light air coastal race in the ICRA Championships that finished this afternoon under spinnaker on Dublin Bay.

Despite a limp forecast, a relatively solid light easterly breeze prevailed for the impressive 12-boat fleet that has gathered at the NYC for the first cruiser-racer National Championships in two years.

Much fancied in these conditions were both the debutante Kaya and Royal Cork Yacht Club's Jump Juice but as it turns out, the well-sailed County Down First 40, Forty Licks (Jay Colville) from Royal Ulster squeezed into second place between the pundit's two favourites.

Of course, Conor Phelan's Ker 37 Jump did well to start at all given the extent of the hull repair that was finished only hours before this morning's race start.

The impressive 12-boat ICRA Nationals Cruisers Zero fleet Photo: Afloat

The impressive 12-boat ICRA Nationals Cruisers Zero fleet Photo: Afloat

Another Northern Ireland entry, the Beneteau 40.7 Game Changer from Cockle Island Boat Club took fourth with Sunfast 3600 Hot Cookie of the host club in fifth place.

Back in the Game - Jump Juice was back on the water just in time for this morning's first coastal race of the ICRA Championships Photo: Afloat

Back in the Game - Jump Juice was back on the water just in time for this morning's first coastal race of the ICRA Championships Photo: Afloat

Results are here. Racing continues over the weekend.

Irish Yacht & Sailing Club Officers' Determined Enthusiasm Has Brought Us Through Pandemic To This Busiest Weekend

There's something about the last weekend of August which makes it a specially pivotal time in Irish sailing. And in this weird pandemic-emergence period, there's an extra sense of individually-tailored controlled events being added to the programme to meet immediate demand – pop-up regattas, in other words - while established fixtures get an extra jolt of enthusiasm at a time when we still feel we might just know what's going on.

For this sense of a viable restriction-exiting road-map has been given a bit of a bruising with the news coming in that the latest accelerating infection situation in New Zealand is going to cause a complete shutdown on sailing events and other happenings afloat there from September 1st. It is a matter of accentuated pain, as it's their first day of Spring when there's always an extra zest in the air in one of the world's most boat-oriented countries. And it comes at a time when the rest of the sailing world really do owe the Kiwis big time, for they're the country that managed to give us the America's Cup 2021 back in March as a source of hugely welcome distraction when almost all of the rest of us were leading troglodyte-like lockdown existences.

In fact, it's time and more to salute all those who have literally kept the sailing faith going through the dark shutdown, keeping the clubs and classes in good heart whatever pessimists might have thought, and then getting our sport moving again just as soon as possible.

The America's Cup 2021 off Auckland. Having provided the sailing world with visions of exciting sport in March 2021, New Zealand now faces a total pandemic-induced boating shutdown from September 1st.

The America's Cup 2021 off Auckland. Having provided the sailing world with visions of exciting sport in March 2021, New Zealand now faces a total pandemic-induced boating shutdown from September 1st.

We have been living through a period of almost two years now in which a certain steely and determinedly cheerful optimism has been central to the job description of any Irish yacht and sailing club Commodore or Admiral, or whatever designation the senior position carries. People need to aspire to be the top honcho for many years in order to acquire the necessary knowledge of how a club functions through working in more junior roles. And on top of that, they have to willingly accept that for the actual period in the senior position, they have to be physically present almost non-stop in or at the club itself, and with its activities afloat and ashore.

So it takes little imagination to visualize the mental re-shaping which was needed to take with those individuals who had been preparing themelves to fill the lead position, only to find that the environment in which they'd be leading was changing by the minute, and changing very adversely at that.

Admiral Colin Morehead of the Royal Cork YC has kept up his members' spirits through a very challenging period in the club's long and unique history. Photo: Robert Bateman

Admiral Colin Morehead of the Royal Cork YC has kept up his members' spirits through a very challenging period in the club's long and unique history. Photo: Robert Bateman

This was especially the case with the Royal Cork in Crosshaven where they were planning to celebrate their Tricentenary on an massive international basis, and at the National Yacht Club in Dun Laoghaire with its 150th coming up. With lesser men, the disappointment of shutdown would have been almost a knockout blow. But Commodore Martin McCarthy at the NYC and Admiral Colin Morehead at the Royal Cork showed they were of tougher stuff, for if the sheer cruelty of these adverse events ever depressed them, neither of them ever showed it in public.

On the contrary, they were always there, cheerfully chivvying people along as fresh possibilities came over the changing horizon. And in recent weeks, Colin Morehead has been a bundle of energy and enthusiasm, keeping the show on the road in the big-fleet Irish Laser Nationals, while he's making this a very special weekend indeed at Crosshaven and on Cork Harbour and the seas thereof, with the AIB RCYC Tricentenary Regatta starting with a Parade of Sail this (Saturday) morning at 11:30hrs across at Haulbowline, going on into a racing programme which will bring the fleets of keelboats and dinghies across the harbour for a finish towards Crosshaven and re-assembly at the RCYC for a barbecue.

Tomorrow (Sunday) is the RCYC itself as the focal point, with racing in the morning and members invited to bring picnics to sustain them through a long and busily enjoyable day for which, praise be, it looks as though the weather will hold up, although a spot of morning mist may need to be factored into the day's programme before the sunshine burns it off.

Kieran Collins Olson 30 Coracle VI (RCYC), winner of IRC2 in the 2021 Sovereigns Cup in Kinsale. Photo: Robert Bateman

Kieran Collins Olson 30 Coracle VI (RCYC), winner of IRC2 in the 2021 Sovereigns Cup in Kinsale. Photo: Robert Bateman

Meanwhile, round the corner in Kinsale, in late June Commodore Michael Walsh had led his team in a carefully-managed COVID-compliant Sovereigns Cup Regatta, which gave Irish sailing a real boost just when it was most needed, a shot of confidence to take on new opportunities.

Up in Dublin Bay at the National, Martin McCarthy has now completed his period as Commodore - to be succeeded by Conor O'Regan - after seeing through an outstandingly successful Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race and the launching of Donal O'Sullivan's excellent NYC history, and he left a club in the best possible heart to take on the co-running of the Laser 4.7 Worlds with the Royal St George from August 7th to 14th, the first pandemic-emergent international sailing event in Ireland, and brilliantly-run within regulations utilizing experience which has been accumulating ever since Dun Laoghaire's first regatta in 1828.

It was another former NYC Commodore, Peter Ryan who - in his current role as Chairman of ISORA - was central to the immediate availability of Yellowbrick trackers when what were in effect pop-up offshore races came on stream in both 2020 and 2021, the outstanding success being the Fastnet 450 of 2020 which provided an outlet for the pent-up energies of both the 150-year-old NYC in Dublin, and the 300-year-old RCYC in Cork, with participation from several clubs and a winner in Nieulargo (Denis Murphy, RCYC).

People who have kept the show on the road – Martin McCarthy when Commodore of the National YC with Ann Kirwan, Commodore Dublin Bay SC.

People who have kept the show on the road – Martin McCarthy when Commodore of the National YC with Ann Kirwan, Commodore Dublin Bay SC.

In the Royal St George YC - the lead organiser for the big Laser event - Richard O'Connor succeeded Peter Bowring as Commodore after the latter had skillfully steered the club through the most severe part of the lockdown and into an increased level of activity afloat.

The Royal Irish YC, for its part is in a specially demanding position, as its prime location right on the marina makes it a natural focal point, particularly for big boat events. But in Commodore Pat Shannon, they've a sailing enthusiast whose knowledge of just how the town and the harbour and the bay interact is unrivalled, and he has quietly played a key role in the gradual buildup of Dun Laoghaire's sailing activity, both through and beyond the regular 200-boats-plus weekly programme of Dublin Bay Sailing Club, for which DBSC Commodore Ann Kirwan deservedly took over custodianship of the Mitsubishi Motors "Sailing Club of the Year 2021" trophy a week ago.

Over on the west coast, they've less continuous experience of sailing organisation in Galway, for although the Royal Galway Yacht Club was active in both Galway Bay and Lough Corrib after its formation in 1870, it was wound up in 1940, and it wasn't until 1970 that a club emerged again in the form of Galway Bay SC, with its base ultimately at Renville near Oranmore. Had things been normal, last year would have seen the Golden Jubilee celebrated in style, but like the more senior National YC and the even more senior Royal Cork YC, they've saved what is transferable to celebrate in 2021, and just last weekend – as reported in Afloat.ie – GBSC Commodore John Shorten led his member and visitors in the remarkable 46-boat Lambs Week Cruise in Galway Bay out to the Aran Islands and on to Roundstone, a complex event which included two races, the highlight being an almost perfectly-calculated pursuit race round the Aran Islands.

John Shorten, Commodore of Galway Bay Sailing Club

John Shorten, Commodore of Galway Bay Sailing Club

Back on the East Coast, the multi-facilities Howth Yacht Club has successfully re-configured its services and programme to make the best of the changing environment of restrictions under Commodore Ian Byrne and his successor Paddy Judge, and their switched-on reading of the situation was very clearly seen on Saturday, June 12th. The powers-that-be in their wisdom had selected Monday June 7th as the first day on which the most stringent limitations were to be lifted, and almost within minutes Howth YC declared that their annual 119-year-old Lambay Race would be staged as a club-only event on June 12th. For some boats this resulted in a hyper-fast fitout, but on the day 78 keelboats came to the line, an impressive turnout after what - for some - had been a long hibernation, as not everyone had chosen to avail of the brief easings of 2020

Keeping sailing going…..HYC Commodore Ian Byrne and his successor Paddy Judge demonstrating the Two Metre Social Distance Rule. Photo: HYC

Keeping sailing going…..HYC Commodore Ian Byrne and his successor Paddy Judge demonstrating the Two Metre Social Distance Rule. Photo: HYC

As with the key figures in clubs, so too do One-Design Classes have some vital personnel who encourage the show along on the road. And while they tend to be much more invisible than the necessarily conspicuous sailing club Flag Officers, these back-room encouragers have been having as good a pandemic as possible, with the classic local classes finding that the enforced home time encouraged boat restoration, while major milestones in class histories acquired extra significance, with the Centenary Races of the Mylne-designed 29ft River Class on Strangford Lough – the world's first Bermuda-rigged One-Design – attracting deserved attention to a class which normally lives at a certain level of splendid isolation, yet was in the spotlight to see Graham Smyth in Enler taking the coveted Centenary Trophy.

Graham Smyth's Enler, Centenary Champion of the Strangford Lough River Class. Photo: W M Nixon

Graham Smyth's Enler, Centenary Champion of the Strangford Lough River Class. Photo: W M Nixon

Class Associations that function successfully at a nationwide level have proven very effective at coming through the dark times, and the International Dragons, the Flying Fifteens and the GP14s work very well in meeting a more focused demand than the broadly-appealing all-popular Laser, which is always in a win-win situation.

The GP 14s at one of their club strongholds are a force to behold, and today (Saturday) they've descended in strength on Sutton Dinghy Club for the Annual Regatta which – with sunshine forecast and northeast sea breezes coming over the Hill of Howth – may even provide smooth water suntrap sailing.

There'll be other events looking to avail of this weekend's burst of late summer weather, sometimes at the last minute. But as well, by this time next weekend the ICRA Nationals 2021 will be fully under way in Dublin Bay, hosted by the National Yacht Club with 63 boats lined-up for a series whose results will be scrutinized every which way, as certain teams are hinting at being part of the new wave of a flotilla of Mark Mills-designed Cape 31s which – they say – will feature on both the south and east coasts next year.

Meanwhile, with international travel continuing to be very problematic, it leaves Irish participation in certain rather special Autumn contests overseas as still being a matter of speculation. In the circumstances, it's good to hear that Conor Doyle's Xp50 Freya from Kinsale is safely positioned in the Mediterranean in the countdown towards late October's Middle Sea Race from Malta. And the word is they've already made their mark with a fifth place in the Palermo to Monaco Race.

There's something about the way that Steve Morris and his boat-building team in Kilrush are restoring the 1903-vintage Dublin Bay 21s that speaks to people with only a vague notion of the sea and sailing. The class association circled around Fionan de Barra and Hal Sisk may have made straightforward sailing accessibility a central theme of their continuing project. But the restoration work which has been done is in itself so accessible, so comprehensible and obvious to anyone with the slightest appreciation of quality workmanship, that it is inspiring in its own right.

Thus while several merging deluges of wind-flattening rain may have conspired to try and take the quiet delight out of yesterday (Friday) evening's return of the first three restored boats, it was the glowing quality of the glorious workmanship that led to flights of oratory which provided a vision for the new life of Dun Laoghaire Harbour, now that its administration has been taken over by Dun Laoghaire Rathdown County Council.

DB 21 saviour and architect Fionan de Barra is at the heart of a highly artistic group in the National YC – NYC member Fergal MacCabe created this carpaccio of Dun Laoghaire for the cover of the very informative brochure abut the restoration of the class

DB 21 saviour and architect Fionan de Barra is at the heart of a highly artistic group in the National YC – NYC member Fergal MacCabe created this carpaccio of Dun Laoghaire for the cover of the very informative brochure abut the restoration of the class

In a lineup of star speakers, it was Lettie McCarthy, An Cathaoirleach of Dun Laoghaire Rathdown CC, who really brought the audience of sailors and well-wishers to life. For in talking of the effect that seeing the restored boats had made on her, she thought aloud and eloquently of how well a properly-organised boat-building school would fit into plans for revitalising the town's inner harbour waterfront.

With another speaker, you might have thought this was the offhand donation of a vague notion as a hostage to fortune. But this was a serious and considered viewpoint which gave a real edge to a gathering on the forecourt of the National Yacht Club which, until then, had been mainly thinking of a shared sense of relief that the Dublin Bay 21s were safely home, despite the best efforts of Storm Evert to assault the southeast of Ireland on Thursday night.

Nearly home. A brief flash of sunlight on Sandycove as Naneen – skippered by Hal Sisk - approaches Dun Laoghaire. For racing trim, the DB21 needs some weight forward, but they're usually confined below. Photo: W M Nixon

Nearly home. A brief flash of sunlight on Sandycove as Naneen – skippered by Hal Sisk - approaches Dun Laoghaire. For racing trim, the DB21 needs some weight forward, but they're usually confined below. Photo: W M Nixon

Fionan de Barra and a crew of DB 21 veterans on Garavogue, built by James Kelly of Portrush in 1903. Class lore would have it that Garavogue is the only DB 21 which hasn't sunk at some stage in her long life. Photo: W M Nixon

Fionan de Barra and a crew of DB 21 veterans on Garavogue, built by James Kelly of Portrush in 1903. Class lore would have it that Garavogue is the only DB 21 which hasn't sunk at some stage in her long life. Photo: W M Nixon

In fact, Storm Evert may well become a special meteorological Case Study some day, as he or she behaved very oddly indeed, departing eastward past the Tuskar Rock in a state of self-collapse from which the only result was seemingly solid rain and very little useful wind.

Despite that, a vigorous group of eleven Howth 17s came across the bay to salute the Return of the Prodigals, and even if some of them needed direct assistance from Race Officer Jonathan O'Rourke in the DBSC Committee Boat Mac Lir to overcome local calm in the middle of the bay, others came out of the downpour in full sailing style with topsails still set as they swept into the National's mini marina.

This was a fast-moving manoeuvre which put the fear of God into some observers, but those of us who know the Seventeens are well aware that they can usually get stopped before there's the sound of breaking glass, while if all else fails, their bowsprits can always double as a useful crumple zone.

There are at least two topsail-toting Howth 17s seen here arriving into the NYC's mini marina, in a hurry as the rain begins in earnest, yet somehow they stop in the nick of time. Note how the two masts of the DB21s beyond are carrying classically-hoisted DBSC burgees. Photo: W M Nixon

There are at least two topsail-toting Howth 17s seen here arriving into the NYC's mini marina, in a hurry as the rain begins in earnest, yet somehow they stop in the nick of time. Note how the two masts of the DB21s beyond are carrying classically-hoisted DBSC burgees. Photo: W M Nixon

In the shambolic weather, there was adjudged to be no clear winner of the Seventeens' race from Howth, and thus the Island Cup which the DB21s had discovered unused in the NYC was given not to an individual boat, but to the whole class simply for being their own wonderful selves.

The Island Cup dates from 1906, but was first awarded to the DB21s in 1953 by one of their own, District Judge McLaughlin. If memory serves aright, in the almost petrol-free and rare rail service times of The Emergency, if the Judge had cases to hear in Wicklow, he would sail there in his DB21, crewed by the barristers who would be acting for the litigants, thereby reinforcing Hal Sisk's statement that the DB 21s were the world's first cruiser-racer class.

Be that as it may, for some of the not-as-young-as-they-used-to-be former DB 21 sailors who made the voyage up from Arklow, it was at times quite rugged, with Wicklow Head, as usual, doling out quite a pasting. Nevertheless, they were pleased to find old skills returning, with Paddy Boyd delighted with the discovery that although it is a long time since he last sent a burgee to the masthead in classic style, he did so with the DBSC emblem at the very first attempt – it's like re-discovering you still know how to ride a bike, says he, it never leaves you.

Estelle was the third of the first batch of restored DB21s to travel from Kilrush to Arklow. Photo: Steve Morris

Estelle was the third of the first batch of restored DB21s to travel from Kilrush to Arklow. Photo: Steve Morris

The work goes on – Estelle's place in Kirush has now been taken by Geraldine, owned for many years by the Johnston family. Photo: Steve Morris

The work goes on – Estelle's place in Kirush has now been taken by Geraldine, owned for many years by the Johnston family. Photo: Steve Morris

Nevertheless, for many of us present at this determinedly and then effortlessly cheerful gathering, it was the first serious socialising after many a long locked-down month, and some of us confessed that while we may never have been overly blessed with social skills, there's a lot more to working a crowd – even one of only 200 people – than there is to riding a bike.

Thus the real meaning of the return of the DB21s - and the many stories which emerged from this party - will start to make more sense when they've had their first proper DBSC race next Tuesday evening.

As it is, we now have it as official that the Council are very positive about the notion of a Dun Laoghaire Boat Building School - even if a voice at the back of the crowd was heard wondering if an astrodome for the entire Harbour and immediate waterfront area might not be a better idea.

Dublin Bay 21 Arrival into Dublin Bay Photo Gallery By Michael Chester

It’s called the SCORA Fastnet 450 which is a zinger of a name, whatever it means, and right now it’s taking shape as we go along in best pop-up style, having come centre stage after the Round Ireland Race was COVID-cancelled last week. And for those who would complain that it’s all much too short notice, at variance with the best traditions of sensible sailing organisation, well, they’re wasting their breath. For as we shall see in due course, the daddy of them all, the Kingstown to Queenstown or Dun Laoghaire to Cobh Race of July 1860, was something of a pop-up event too, all of those 160 years ago.

But to return to the here and now, the Fastnet 450 starts off Dun Laoghaire under the auspices of the National Yacht Club in two weeks time on Saturday, August 22nd, and the race begins with 150 years in the kitty, as that’s the anniversary the National YC is marking this year.

Busy times at the National Yacht Club, 150 years old this year

Busy times at the National Yacht Club, 150 years old this year

The course then zaps southward down the East Coast leaving the Tuskar Rock to starboard before heading on out past the Coningbeg for the long haul (it’s not always to windward) along the south coast to the Fastnet Rock, which is then left to starboard in a handbrake turn as the fleet heads back up the coast to finish at Roche’s Point at the entrance to Cork Harbour, and the social-distance complying welcome of Royal Cork Yacht Club at Crosshaven.

Where it all began, and still at the heart of it. Crosshaven with the Royal Cork YC in prime position Photo: Bob Bateman

Where it all began, and still at the heart of it. Crosshaven with the Royal Cork YC in prime position Photo: Bob Bateman

The RCYC then nonchalantly pops its cool 300 years of existence into the shared temporal pot, and bingo, we’ve the Fastnet 450, which somehow manages to seem right up to the minute and yet properly historical a well.

South Coast Offshore Racing

Clearly there are some very innovative and energetic minds in the South Coast Offshore Racing Association at work here, with SCORA Commodore Johanna Murphy of Cobh and Royal Cork YC’s Rear Admiral Annamarie Murphy working with Olympian Mark Mansfield. Speed is of the essence, and they managed to get the officially-vetted details in proper form up on the Royal Cork YC website at noon yesterday (Friday), so if this alleged Sailing on Saturdays seems to be hitting your screen well before Saturday in Ireland, please loosen up a bit – it’s already Saturday in Ulan Bator……

The Notice of Race for the Fastnet 450 - download the full document below as a PDF attachment

The Notice of Race for the Fastnet 450 - download the full document below as a PDF attachment

In the meantime, some targeted marketing (i.e. ringing around likely runners and putting up a click spot for expressions of interest on Afloat.ie on August 2nd) was extremely encouraging, with 22 boats very strongly interested even before it went official. Being quite late in the season, those who think it’s a good idea were nevertheless a bit concerned that Irish Sea boats mightn’t want to end up positioned in Cork in late August, but these fears were groundless, as the preliminary indications showed a skewing of two-thirds East Coast, and one-third Cork.

Of course, with this emphasis on the ability to accommodate late entry decisions, some boats may wait until they see what the ten day forecast looks like before committing, but it is highly likely that the Cork fleet will be into double figures by the time the boats are being positioned to Dublin Bay. And though some of them will leave that to the delivery crews in the days immediately prior to race, if enough are planning to do it over the weekend beforehand (i.e 14th to 16th August) maybe they could make a little race out of that too, for people are just gasping for any sport they can get.

SCORA’s Fastnet 450 team are Johanna Murphy (Commodore), Mark Mansfield, and Annamarie Murphy (Rear Admiral, Royal Cork YC)

SCORA’s Fastnet 450 team are Johanna Murphy (Commodore), Mark Mansfield, and Annamarie Murphy (Rear Admiral, Royal Cork YC)

As it is, for now on Friday, August 7th it’s a list good on quality and quantity, with the pace-setters from the south coast inevitably being the top boats from last weekend’s Kinsale-Fastnet-Kinsale Race, where Mark Mansfield guiding Cian McCarthy’s new Sunfast 3300 Cinnamon Girl found himself sailing on the same IRC rating of 1.023 as Denis & Annamarie Murphy’s Grand Soleil 40 Nieulargo, which had the formidable talent of Nin O’Leary on the strength to provide an Olympian contest.

As reported, Nieulargo made a breeze of it, finishing five minutes after noon on the Saturday to take line honours, and though Cinnamon Girl was next in half an hour later, those rating figures were inescapable, and Finbarr O’Regan’s Artful Dodger (KYC) and Stephen Lysaght’s Reavra Too, also KYC, slipped into second and third on CT before Cinnamon Girl came home on fourth overall.

Sandwiched…..Cian McCarthy’s Sunfast 3300 Cinnamon Girl finds herself being squeezed between eventual overall winner Nieulargo (Grand Soleil 40, left) and Tom Roche’s Salona 45 Meridien as the Kinsale-Fastnet-Kinsale fleet makes its way down Kinsale Harbour. Photo: Robert Bateman

Sandwiched…..Cian McCarthy’s Sunfast 3300 Cinnamon Girl finds herself being squeezed between eventual overall winner Nieulargo (Grand Soleil 40, left) and Tom Roche’s Salona 45 Meridien as the Kinsale-Fastnet-Kinsale fleet makes its way down Kinsale Harbour. Photo: Robert Bateman

However, it’s early days yet, and the paid-up within two hours listing (in arrival order) for the Fastnet 450 already shows plenty of talent for form spotters and results-predictors to pick over as we go through the stages of the growing entry list and developing weather towards the start.

As of 3.0pm Friday, the boats are Red Alert (Rupert Barry), Aplusd (Flynn Kinsman), Humdinger (John Coleman), Blue Oyster (Mark Coleman), Nieulargo (Denis & Annamarie Murphy), YO YO (Brendan Coughlan), Valfreya (Mark & David Leonard, Juggerknot 2 (Andrew Algeo) and Blackjack (Peter Coad).

Andrew Algeo’s J/99 Juggerknot Two is in the first wave of entries for Fastnet 450. Photo: Afloat.ie

Andrew Algeo’s J/99 Juggerknot Two is in the first wave of entries for Fastnet 450. Photo: Afloat.ie

Some people find the speed of development of this race unsettling, others find it stimulating, but either way we’re inevitably reminded of the great General Dwight D Eisenhower, who gave traction to the military theory that ultimately plans are worthless, but planning is everything. He never claimed it as his own original idea, but after he’d enshrined it, its apparently almost vulgar dismissal of accepted establishment beliefs came to be seen as disguising the brutal truth.

For if ever there was a peacetime period when set plans are useless, but continuous planning is essential, then we’re living through it right now in sailing as in everything else. For sure, you have to set out fixed times for races starting and the other event-planning paraphernalia. But both organisers and participants now have to realize that it all may have to be changed at very short notice, and then maybe changed again.

The SSE Renewables Round Ireland Race from Wicklow was one of the last major offshore races scheduled for 2020 which involved a significant shoreside element, for it is inextricably associated with the town and club which has been running it for forty years.

It was that indispensable shoreside element which was its undoing. But even as the cancellation of 2020’s Round Ireland was moving remorselessly up the agenda, the Irish Sea Offshore Racing Association was demonstrating that it was possible to stage offshore events of limited scope by running races aimed separately at its fleets on each side of the channel, with the courses set within national territorial waters, and virtually no direct shoreside involvement at all - they were races for sailors run by sailors, but using robots and trackers

However, the clear boundaries to this approach became evident as we neared the date for the first cross-channel foray, which would have raced the combined fleet race from Dun Laoghaire in Ireland to Pwllheli in Wales this weekend. But the different regulatory systems in each jurisdiction raise difficulties which would have been exacerbated if an international entry gathered for the Welsh IRC Championship in Tremadoc Bay, and in a sudden yet inevitable announcement last weekend, those plan were abandoned.

A superb all-rounder – the Grand Soleil 40 Nieulargo (Denis & Annamarie Murphy) will be looking to make it the double for August with the Fastnet 450 after winning the Kinsale-Fastnet-Kinsale Race every which way. Photo: Robert Bateman

A superb all-rounder – the Grand Soleil 40 Nieulargo (Denis & Annamarie Murphy) will be looking to make it the double for August with the Fastnet 450 after winning the Kinsale-Fastnet-Kinsale Race every which way. Photo: Robert Bateman

Thus would-be organisers have had to stand back and assess what has or has not been permissible in the developing situation. And that hardy perennial of our sport in Ireland – straightforward club racing with known personnel involvement – is proving to be the backbone of our sailing in 2020.

And in the coastal and offshore scene, as it’s clear the only racing permissible has to be within Irish territorial waters, so the raw logic of a race from Dublin Bay to Cork with a Fastnet-rounding extension was inescapable if there was going to be any meaningful event before the season was out.

It’s essentially the basic race of the absolute essentials. The boat numbers are in Cork Harbour and the greater Dublin area, so boat movement prior to the event is minimized. Autumn will be just around the corner, so Dublin owners will be appreciative of having their boats no further from home than is absolutely necessary.

So how can we claim that the glaringly pop-up element of it all is nothing new, in fact it’s positively historic. Well, back in 1860 the Royal St George Yacht Club in Dublin Bay had organised a week of regattas in early July, and the dedicated Admiral of the Royal Cork Yacht Club, the remarkable Thomas G French of Cuskinny in Cobh - still going strong at the age of 80 years - saw an opportunity for implementing his long-held dream of a distance race from Dublin Bay to Cork Harbour.

But instead of having a great blaring of publicity beforehand for this then-novel idea, he quietly circulated the idea in what we now think of as pop-up style among those owners and skipper – they came from many parts of Ireland and from England too – in the days before the week in Dublin Bay, and during the course of the regatta socialising ashore, he continued to quietly press the idea.

Destination for July 1860….the members of the Royal Cork YC at Cobh (now the Sirius Arts Centre) expected to be able to witness the finish of the race from Dublin Bay close at hand and in comfort, regardless of the flukey winds sometimes found within Cork Harbour