Displaying items by tag: Saoirse

A hundred years ago next Tuesday, June 20th, Conor O'Brien (1880-1952) of Foynes took his departure with some fanfare aboard his 42ft Saoirse from the harbour her skipper preferred to call Dunleary, though most of its citizens saw it as Kingstown, and headed south. Saoirse had been designed in a first-time effort by her owner-skipper, and was newly built by Tom Moynihan in the Fisheries School in Baltimore.

When she returned exactly two years later, on Saturday, June 20th 1925, Saoirse had become the first “yacht” to circumnavigate the world south of the Great Capes of Good Hope and Cape Horn, running down her easting in the mighty westerlies of the Southern Ocean through the vast wastes of sea which, until then, had been solely the province of the much more substantial vessels of government-backed explorers, naval commanders, pirates, global traders, and rapacious whalers.

WORKBOAT-STYLE YACHT

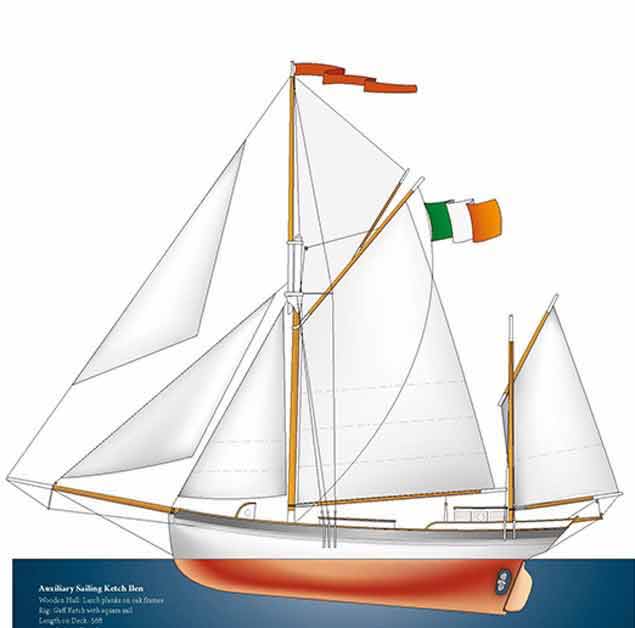

To a casual observer, Saoirse’s yacht status would have seemed questionable. This was no glittering toy for the sport of the rich. On the contrary, her archaic rig and very traditional and largely un-decorated hull was loosely based on the lines of an 1860s Arklow fishing boat, whose looks and sea-keeping qualities O'Brien had come to admire.

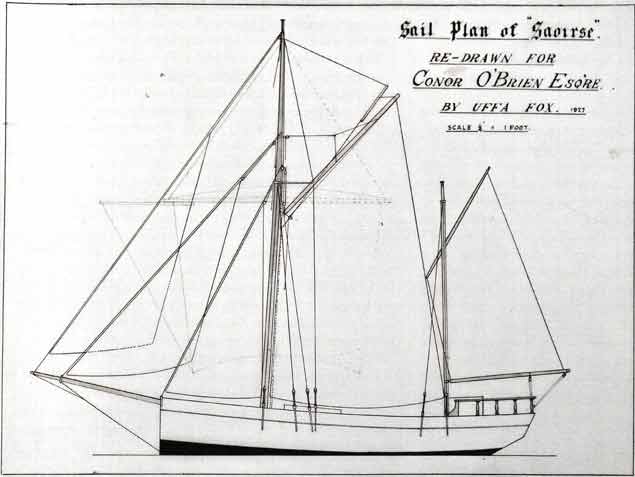

Saoirse. Conor O’Brien’s sail-plan for his first yacht design was essentially for offwind sailing, and the stunsails…

Saoirse. Conor O’Brien’s sail-plan for his first yacht design was essentially for offwind sailing, and the stunsails…

…………were by no means ornamental, adding real speed in light winds. Photo courtesy O’Brien family

…………were by no means ornamental, adding real speed in light winds. Photo courtesy O’Brien family

Yet by any commercial definition, she wasn’t a workboat, for in Irish waters, she sailed under the burgee of the 1831-founded Royal Irish Yacht Club. And abroad, her owner used the additional muscle of the 1880-founded London-based Royal Cruising Club in order to smooth the way in foreign ports and also – through its highly-regarded annual RCC Journal – to help in his need for resources-generating publicity which was also supported by articles in Irish newspapers.

ABNORMAL TIMES, WAR-TORN LOCATIONS

In the early 1920s, undertaking such a project in normal circumstances would have been something special. But the Ireland of the early 1920s was anything but normal, and the voyage of the Saoirse emerged from a time of turmoil. The new vessel - O’Brien’s first yacht design - was built shortly after the War of Independence and during the Civil War, in which her birthplace in West Cork was at the heart of one of the most active theatres of conflict.

It was a time of heightened feeling, of lifelong friendships sundered by opposing opinions and the outcomes of irreversible actions. O’Brien may have been a grandson of Young Irelander William Smith O’Brien of the 1848 rising, but his own father Edward, an extensive land-owner of Cahirmoyle near Foynes in County Limerick, had been largely inactive in politics and generally conservative in outlook for much of his life.

O’BRIEN THE GUN-RUNNER

Yet a period of living in Dublin after schooling and university in England saw the young Conor O’Brien’s opinions crystallising strongly in favour of Home Rule, and he became a fellow-gun-runner - sailing his own ketch Kelpie - with Erskine & Molly Childers with their ketch Asgard in the 1914 gun-running on behalf of the Irish Volunteers.

Erskine & Molly Childers’ Asgard of 1905-vintage as conserved by John Kearon in Collins Barracks Museum in Dublin. In all, three yachts were involved in the 1914 gun-running – Asgard, Conor O’Brien’s Kelpie, and Sir Thomas Myles’ Chotah. Photo: W M Nixon

Erskine & Molly Childers’ Asgard of 1905-vintage as conserved by John Kearon in Collins Barracks Museum in Dublin. In all, three yachts were involved in the 1914 gun-running – Asgard, Conor O’Brien’s Kelpie, and Sir Thomas Myles’ Chotah. Photo: W M Nixon

O’Brien’s English schooling and university experience had seen mountaineering as his primary recreational interest, but regular family holidays at Derrynane in Kerry and subsequent experience afloat at Foynes had strengthened a longtime interest in sailing to such an extent that, in his Dublin period in the first dozen or so years of the 20th Century, he took the step in 1910 of selling his house in the fashionable Fitzwilliam area of the city (where he’d been a founder member of the United Arts Club in 1907) in order to buy the 1870-built 48ft Kelpie.

She was a heavily-rigged cutter, but for ease of handling, he reduced the sailplan to ketch rig, and continued to build his seagoing experience with coastal projects such as a round Ireland cruise in 1913, while formalising his knowledge of navigation through enrolment in the Royal Naval Reserve.

“ANGER MANAGEMENT” PROBLEMS

He managed this despite being a notoriously short-tempered individual who could fall out with his sometimes voluntary crews as readily as he could disagree with his naval superiors. For the fact is that in beginning the celebrations of the Centenary of Saoirse’s departure with an Irish Cruising Club/Royal Cruising Club gathering in the Royal Irish YC today hosted by RIYC Commodore Jerome Dowling and ICC Commodore David Beattie, there’ll be a tacit acknowledgement that in any society, Edward Conor Marshall O’Brien would have instantly qualified as a charter member of the Awkward Squad.

But then, amidst the experiences, general maritime knowledge and attitudes of his time, no sensible normal person would have dreamt of setting off in such a small and relatively untested boat with such huge ambitions into what was still largely the Great Unknown.

Yet there was a certain inevitability about it. Two years earlier, while returning from a sailing/mountaineering expedition to The Cuillin Mountains of Skye, O’Brien had found himself obliged to sail single-handed back to Dublin Bay in what was now his floating home, the Kelpie.

THE LOSS OF THE KELPIE

Turning slowly to windward through the North Channel at night aboard Kelpie, O’Brien took off southeastwards from the mouth of Belfast Lough, and set his alarm clock to give himself an off-watch of two hours of sleep in open water. Typically, he furiously blamed the German manufacturers of the clock for the fact that he slept through the alarm. Either way, while Kelpie may have come gently aground on rocks just south of Portpatrick on Scotland’s Galloway coast, she was doomed.

Conor O’Brien aboard Kelpie off the West Coast of Ireland in 1913. Even with her rig reduced to a ketch configuration, Kelpie was a massively heavy challenge for a single-hander. Photo: courtesy O’Brien family

Conor O’Brien aboard Kelpie off the West Coast of Ireland in 1913. Even with her rig reduced to a ketch configuration, Kelpie was a massively heavy challenge for a single-hander. Photo: courtesy O’Brien family

Any salvage of the ship as she began to break up as the tide started to fall was beyond the abilities of O'Brien on his own, and he emerged at Portpatrick out of the morning mist, rowing in the Kelpie’s little dinghy surrounded by his personal possessions, and already thinking of the next chapter in his apparently rather aimless life.

He retreated for mental convalescence to a cottage on the family-owned Foynes Island in the Shannon Estuary, and soon was drawing the lines of his new dreamship. Funds were very limited, so he restricted himself to a chopped-off transom-sterned hull design just 40ft long.

Conor O’Brien’s cottage on Foynes Island, as seen through the rigging of the restored Ilen in 2018. Photo: Gary Mac Mahon

Conor O’Brien’s cottage on Foynes Island, as seen through the rigging of the restored Ilen in 2018. Photo: Gary Mac Mahon

TOM MOYNIHAN, BALTIMORE’S VERY SPECIAL BOATBUILDER

Tom Moynihan in Baltimore seems to have been one of the few people with whom he retained a comfortable working relationship, and thus when Moynihan quietly lengthened the hull with two extra feet of sawn-off counter (reputedly while O’Brien was away from being an almost-constant presence in Baltimore), Tom earned the world sailing community’s eternal gratitude, for at a stroke he gave Saoirse a rather jaunty look that the original O’Brien lines had conspicuously lacked.

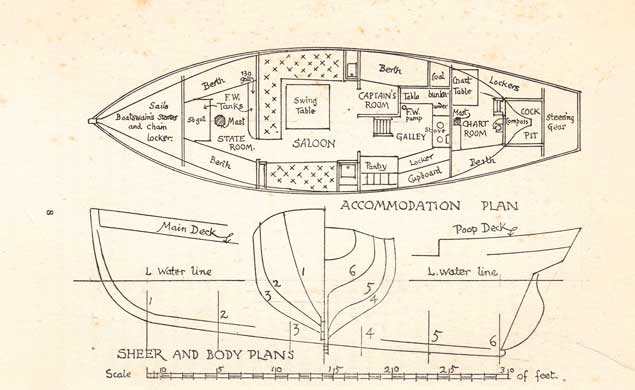

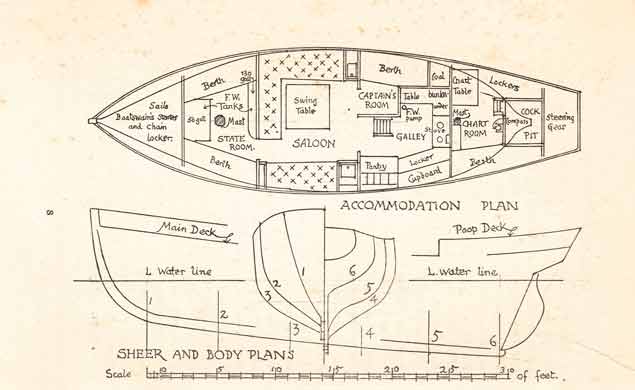

There simply isn’t the space here – or perhaps anywhere – to discuss all the ramifications of Saoirse’s design. Sufficient to say that as a late-flowering architect with an enthusiasm for William Morris’s Arts & Crafts movement, in some ways O' Brien aspired to create a comfortable sea-going cottage. And it’s significant that while Erskine & Molly Childer’s Asgard – otherwise one of the finest cruising yachts of her era – had the galley located uncomfortably forward of the mainmast in the “them and us” attitude of the time, Saoirse’s galley – complete with coal-burning stove – was right aft in the position of least sea-going motion.

Saoirse’s accommodation plan clearly indicated the cooking stove beside its coal bunker located in the position of least motion well aft……….

Saoirse’s accommodation plan clearly indicated the cooking stove beside its coal bunker located in the position of least motion well aft……….

…….and after Conor O’Brien’s marriage to Kitty Clausen in 1928, Saoirse’s potential for cosy comfort could be fully realised. Courtesy O’Brien family

…….and after Conor O’Brien’s marriage to Kitty Clausen in 1928, Saoirse’s potential for cosy comfort could be fully realised. Courtesy O’Brien family

PIONEERING USE OF IRISH TRICOLOUR

It will have come as little surprise that he named his new vessel Saoirse to celebrate the freedom of the new Irish state. But his declaration that he would be flying its tricolour ensign when he reached a foreign port – the first Irish-registered vessel to do so – was tempered by the fact that he left what its citizens generally still thought of as Kingstown with the Royal Irish YC’s British ensign at the top of the mizzen mast.

It was a gesture of unusual diplomacy by the head-strong skipper, but he needed the goodwill of the club and its members. For although in his own mind the voyage had started from Foynes a couple of weeks earlier, where he felt all his voyages began, the Dunleary/Kingstown launching pad was essential to get the publicity machine rolling steadily along.

Saoirse departs from “Dunleary”, June 20th 1923. Although it was intended to fly an Irish tricolour ensign when entering foreign ports, in what most of its citizens still firmly regarded as Kingstown she tactfully flies the Royal Irish YC British blue ensign from the head of her mizzen mast

Saoirse departs from “Dunleary”, June 20th 1923. Although it was intended to fly an Irish tricolour ensign when entering foreign ports, in what most of its citizens still firmly regarded as Kingstown she tactfully flies the Royal Irish YC British blue ensign from the head of her mizzen mast

As it happened, the original Irish ensign on the Saoirse got no further than the first port of call at Funchal in Madeira. The newly appointed Irish Free State consul on that island – with whom O’Brien had a celebratory night of subsequently glossed-over carousal in celebration of the successful completion of both his own and Saoirse’s first ocean passage under sail - was given a present of the flag to fly outside his Consulate, as the new government in Dublin seemed in no haste to issue the trappings of what was an honorary role in such a relatively minor location.

Thus it was some time before a replacement tricolour had been prepared for Saoirse’s entering of foreign harbours – usually to the bewilderment of the port authorities – but meanwhile, the voyage progressed with the usual problems of a new vessel and her archaic rig being solved along the way.

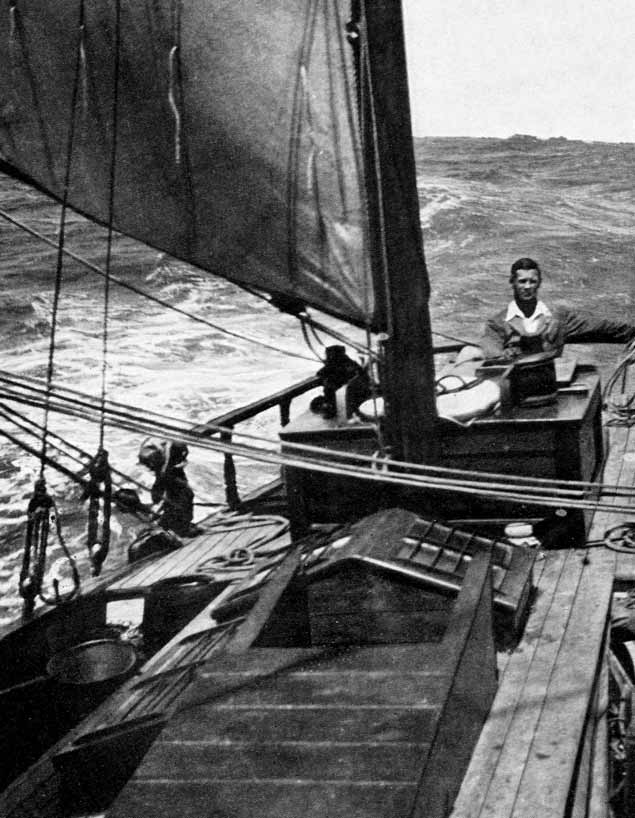

Merrily we roll along. On her first ocean voyage - the 1,300 mile passage from Dublin Bay to Madeira - Saoirse is making excellent and comfortable progress in the Portuguese trades, and Conor O’Brien is at last conspicuously relaxed at the helm. Photo: Courtesy O’Brien family.

Merrily we roll along. On her first ocean voyage - the 1,300 mile passage from Dublin Bay to Madeira - Saoirse is making excellent and comfortable progress in the Portuguese trades, and Conor O’Brien is at last conspicuously relaxed at the helm. Photo: Courtesy O’Brien family.

A LEAP IN THE DARK

This had been an extraordinary departure in many ways. Although he had voyaged many miles offshore in his naval reserve service in the 1914-1918 World War, O’Brien had at most sailed only a couple of hundred oceanic miles. And Saoirse had sailed even fewer. Yet here he and she were, spreading various tales through various publications and conversations about the real purpose of their voyage, purposes which moved between joining mountaineering expeditions in South Africa and New Zealand to the simple ambition of circling the globe south of Good Hope and Horn.

And all this with a new boat which had experienced only the most rudimentary of shakedown cruises, with the passage round from Foynes to be positioned in Dublin Bay probably the longest.

Thus the 1,300 nautical miles of largely oceanic passage to Madeira was something of leap in the dark. But with particularly good sailing in the Portuguese Trades, Saoirse proved to be everything that O’Brien had hoped for and confidently predicted, even if he admitted to those closest to him that the prospect of it all had made him very nervous.

THE “REAL VOYAGE” BEGAN FROM MADEIRA

The arrival in Madeira was over-celebrated, so they more or less had to move on after three days, leaving their Irish tricolour ensign behind yet being rewarded at sea with strong fair winds through the Canariea that gave Saoirse her best day’s run of the entire voyage, 185 miles.

O’Brien was confident that if he could recruit a helmsman whose talent equalled his own in understanding the little ship’s steering needs, then they could break the magic 200-mile barrier. But in his rapid turnover of crew -18 in all during the voyage – there was just one helmsman who began to show sufficient talent. And when he and O’Brien silently witnessed an absolute Mount Everest of a breaking sea building up and crashing over about a mile away in the cross seas of post-storm conditions while south of the Indian Ocean, although nothing was said, both knew that if Saoirse had been caught in up that rogue wave, she was a goner. So at the next port, that most promising of young helmsmen departed without a word.

The restored Conor O’Brien-designed Ilen will depart today from Dun Laoghaire, bound for Madeira. She is seen here during a cruise to Greenland in 2019. Photo: Gary Mac Mahon

The restored Conor O’Brien-designed Ilen will depart today from Dun Laoghaire, bound for Madeira. She is seen here during a cruise to Greenland in 2019. Photo: Gary Mac Mahon

Meanwhile the successful arrival in Madeira had indicated that what had been thought of as a crazy idea by many back home was now being treated with proper seriousness, and as part of the celebrations a flotilla from the Irish Cruising Club, Royal Irish Yacht Club, and Royal Cruising depart from Dun Laoghaire today on a cruise-in-company to Madeira led by the restored 56ft O’Brien ketch Ilen, whose original construction in 1926 - again by Tom Moynihan in Baltimore – was inspired by O’Brien’s successful arrival in the Falklands shortly after his rounding of Cape Horn in December 1924, when the islanders felt a bigger version of Saoirse would provide them with the ideal inter-island service boat.

THE ORIGINS OF ILEN

These days, Ilen is run by the Sailing into Wellness organisation, but in 1997 her retrieval from a retired state in the Falklands in November 1997 was entirely the doing of Gary MacMahon of Limerick, who was becoming more totally involved with each and every passing day into what almost amounted an addiction to seeing that Conor O’Brien’s achievements were properly remembered.

The MacMahon Plan was that his two key boats - Saoirse of 1922, which had been supposedly lost in a hurricane in Jamaica in 1979, and Ilen, which was now back in Ireland and ripe for restoration – would both sail again, whether in a re-built or restored form.

At the time, with the 75th Anniversary of O’Brien’s departure due in 1998, others of us thought some sort of commemorating was appropriate, and at an astonishingly festive gathering in the RIYC – which Gary and many O’Brien relatives attended - a specially commissioned bust of O’Brien, hewn by sculptor Danny Osborne of Beara from the beach-scavenged vertebra of a giant blue whale that would have been of an age to have observed Saoirse sailing past, was presented to the RIYC. And for any normal people, that would have been quite enough until the Centenary came around in 2023.

The Conor O’Brien whalebone bust presented to the Royal Irish Yacht Club in 1998 to mark the 75th Anniversary of the Saoirse voyage. Sculptor Danny Osborne of Beara is best known for his statue of Oscar Wilde in Merrion Square in Dublin

The Conor O’Brien whalebone bust presented to the Royal Irish Yacht Club in 1998 to mark the 75th Anniversary of the Saoirse voyage. Sculptor Danny Osborne of Beara is best known for his statue of Oscar Wilde in Merrion Square in Dublin

ILEN RESTORED, SAOIRSE RE-BORN

But like Conor O'Brien himself, tedious normality is not the default mode with Gary Mac Mahon. He has given more than a quarter of a Century of his best efforts and energy, and ideas to ensure that Ilen has been restored to continue serving a useful purpose, while all the data has been in place to enable the authentic re-building of Saoirse to take place in Liam Hegarty’s boatyard at Oldcourt on the Ilen River in West Cork, where Ilen had been restored.

Thanks to the resources of Fred Kinmonth, Saoirse has been re-born, and for the first time ever, she and Ilen sailed together at last month’s Baltimore Wooden Boat Festival, with Saoirse now identifying as an icon of West Cork. And Gary Mac Mahon, his 27-year mission magnificently completed, has stood back from day-to-day involvement with either vessel.

Gary Mac Mahon at the helm of Ilen in Greenland in 2019

Gary Mac Mahon at the helm of Ilen in Greenland in 2019

CENTRAL TO WORLD SAILING HISTORY

The great voyage of the Saoirse is now seen as a cornerstone of world sailing history. In 1923 she was noticed by only a few when she arrived in Madeira, but this time the Ilen – with the initial flotilla expanded to a fleet as Iberian and Mediterranean-based boats of the ICC and the RCC join the trail – will begin an official visit on July 3rd – the Centenary of O’Brien’s arrival – inaugurating a prodigious welcome and round of celebrations organised by the island’s hospitality dynamo, Catia Carvalho Esteves, and the Clube Naval de Funchal.

The projects completed or initiated through the inspiration of Gary Mac Mahon since 1997 are a little short of miraculous. Conor O’Brien is now remembered, and his achievements are appreciated. All we need to hear is that, in some hidden cupboard of the Irish Consulate in Funchal, they’ve discovered a hundred-year-old Irish tricolour.

“A jaunty little ship”. Fred Kinmonth’s new Saoirse – seen here being stern-chased by the Pilot Cutter Marian during the Baltimore Wooden Boat Festival in May 2023 – had her appearance vastly improved thanks to shipwright Tom Moynihan’s insistence in 1922 that she be given an extra 2ft in overall length at the stern, with an up-lifting sweep to the sheerline. Photo: Robbie Murphy

“A jaunty little ship”. Fred Kinmonth’s new Saoirse – seen here being stern-chased by the Pilot Cutter Marian during the Baltimore Wooden Boat Festival in May 2023 – had her appearance vastly improved thanks to shipwright Tom Moynihan’s insistence in 1922 that she be given an extra 2ft in overall length at the stern, with an up-lifting sweep to the sheerline. Photo: Robbie Murphy

With just three weeks to go to the Centenary of the departure from Ireland on June 20th 1923 of Conor O’Brien’s world-girdling 42ft Baltimore-built ketch Saoirse, the public debut of the re-born Saoirse (Fred Kinmonth) at last weekend’s Baltimore Wooden Boat Festival added an extra resonance to an already multi-faceted interaction of events afloat and ashore at West Cork’s “Sailors’ Capital”.

We’re indebted to the busy Robbie Murphy of Sherkin Island (his home base for an active oyster fishery) for taking time out from his own sailing to record some of the images of an extraordinary and historic occasion which – as in many events in times past – Baltimore took in its stride.

The “standard size” Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter Marian (Dom Ziegler) emphasises Saoirse’s modest dimensions. Photo: Robbie Murphy

The “standard size” Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter Marian (Dom Ziegler) emphasises Saoirse’s modest dimensions. Photo: Robbie Murphy

It says much for the variety of the fleet attracted to this annual gathering that there were many boats there almost as interesting as Saoirse herself, not least of them being the restored 56ft O’Brien trading ketch Ilen of 1926 vintage, which now plays a key role in the Sailing into Wellness programme.

The 1926-vintage Ilen, restored by 2011 through the Ilen Project of Limerick directed by Gary MacMahon, returns to her birthplace of Baltimore. Photo: Robbie Murphy

The 1926-vintage Ilen, restored by 2011 through the Ilen Project of Limerick directed by Gary MacMahon, returns to her birthplace of Baltimore. Photo: Robbie Murphy

Summertime below the Baltimore Beacon for (left to right) Marian, Holly Mae, Willing Lass and Guillemot. Photo: Robbie Murphy

Summertime below the Baltimore Beacon for (left to right) Marian, Holly Mae, Willing Lass and Guillemot. Photo: Robbie Murphy

But in the end, all eyes were drawn to Saoirse, looking at her most jaunty in her attractive livery and tanned sails. There remains one dominating and abiding impression. By today’s standards, she’s a small boat. It may have been festival time as she sailed about Baltimore Harbour in company with other fascinating craft, but there was an underlying seriousness in realizing that the exact original of this “bluff-bowed little boat” really did pioneer the Great Southern Route south of the Great Capes entirely on her own, far indeed from the comforting conviviality of West Cork.

Jeremy Irons’ Oldcourt-built Willing Lass and the Galway Hooker Loveen. Photo: Robbie Murphy

Jeremy Irons’ Oldcourt-built Willing Lass and the Galway Hooker Loveen. Photo: Robbie Murphy

Dreamtime in Baltimore – Ilen heads seaward into the promise of a summer’s day

Dreamtime in Baltimore – Ilen heads seaward into the promise of a summer’s day

Ireland's World-girdling Saoirse Is Re-born - All Welcome At Thursday's Skibbereen Launching Of Photo-Book Of The Magical Process

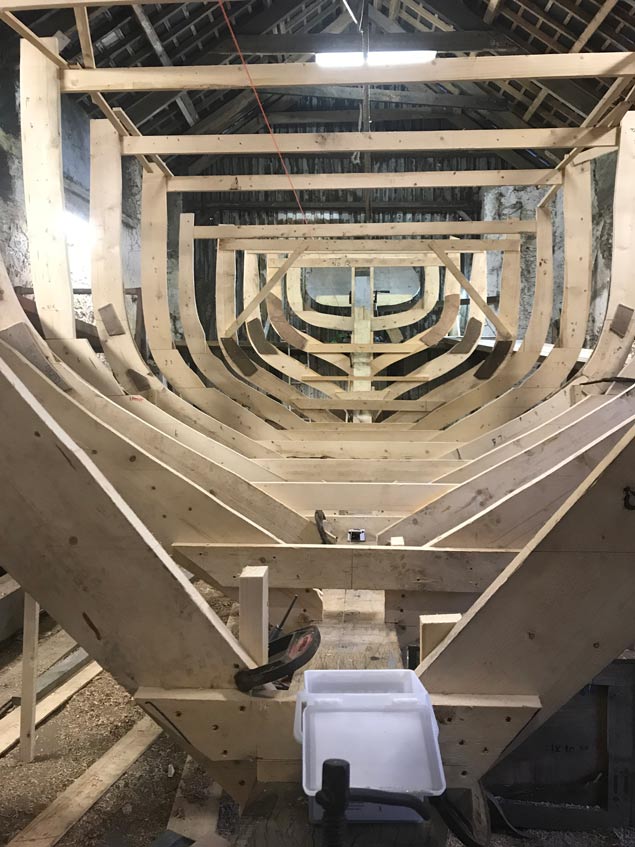

Anyone who doesn't respond at several emotional levels to the atmosphere in an ancient boat-building shed when a traditional wooden boat is being re-created in the time-honoured style can only be soul-dead. And when the boat in question is Conor O'Brien's 1922-built 42ft Cape Horn-pioneering ketch Saoirse, with the re-birth happening for owner Fred Kinmonth in Liam Hegarty's enchanted space in The Old Grain Store (aka The Top Shed) at Oldcourt near Baltimore, then the enchantment is total.

Inevitably, the sacred mood in the shed begins to evaporates as soon as the boat leaves her sheltered place of birth to be readied for

launching. But fortunately the entire process of building Saoirse has been recorded by West Cork photographer Kevin O'Farrell, who hung on until he could get the first photos of the 2022 Saoirse sailing for the very first time in February this year, and then he set to on completing the production of the evocative photobook of the entire process.

It's a real come-all-ye launching in the West Cork Hotel in Skibbereen at 7.0pm this Thursday, April 20th. Everyone of goodwill is welcome, and the book-launching honours are being performed by Cormac Levis, the guru and conscience of the traditional boat movement in West Cork. This will be a uniquely West Cork occasion which will offer an early opportunity to savour the spirit of what is going to be a very special and unrepeatable year for all Conor O'Brien and Saoirse enthusiasts.

The spirit of the re-born Saoirse is captured in this February 2023 Kevin O'Farrell photo taken off Baltimore. Photo: Kevin O'Farrell

The spirit of the re-born Saoirse is captured in this February 2023 Kevin O'Farrell photo taken off Baltimore. Photo: Kevin O'Farrell

The Journal has highlighted the upcoming centenary of Irish yachtsman Conor O’Brien’s pioneering circumnavigation.

In June 1923, Limerick man O’Brien set off on his yacht the Saoirse — named after the then newly created Irish Free State — on the two-year voyage that was to make him the first Irish amateur to sail around the world.

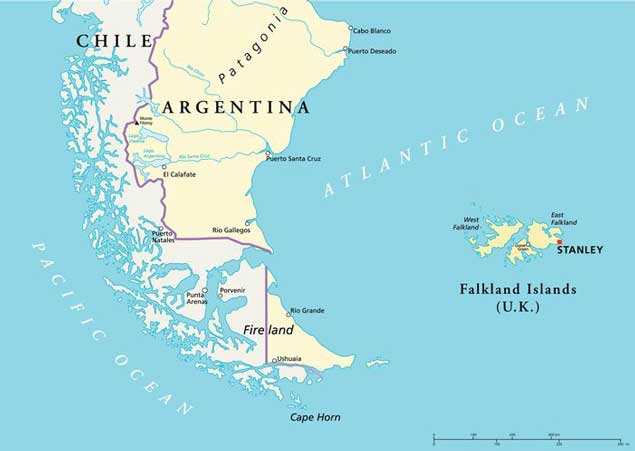

His indirect route across the southern oceans, following the winds, took him past the three great capes: South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, Australia’s Cape Leeuwin and South America’s Cape Horn.

For many decades, however, O’Brien’s achievements were little more than a footnote in Irish history, due in part to his aristocratic background as the country forged a new identity post-independence.

But his legacy has been revived in more recent years, thanks to the traditional boat-building initiative in Limerick inspired by O’Brien’s Ilen — a similar vessel to the Saoirse that he had built in Baltimore for the Falkland Islands in 1926.

And what’s more, Saoirse herself re-emerged in 2018 in West Cork, where the 42ft ketch is proudly sailing once more.

The Journal has much more on the story HERE.

Down in West Cork, they have a way of quietly getting on with things until a major waypoint is inevitably passed in the project, and then we’re into new territory. For two or three years now, Liam Hegarty and his team of master shipwrights at Oldcourt Boatyard on the River Ilen have been engaged in constructing a re-creation of the 42ft Baltimore-built Saoirse. Aboard her, Conor O’Brien (1880-1952) of Foynes Island in the Shannon Estuary sailed round the world with several crew south of the great Capes and back to Ireland in exactly two years, between June 20th 1923, and June 20th 1925.

This means that Saoirse was being completed, commissioned and trial-sailed during the Civil War. While we don’t precisely know her launching date, it’s a fact that in August 1922 she was carrying passengers and mail out of West Cork, as the area’s road and rail communications had been cut off in the ongoing conflict.

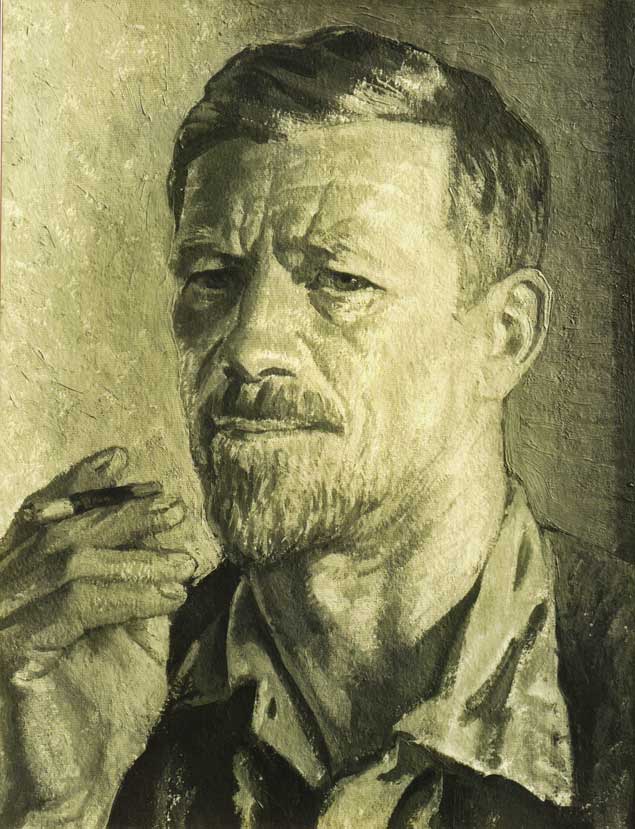

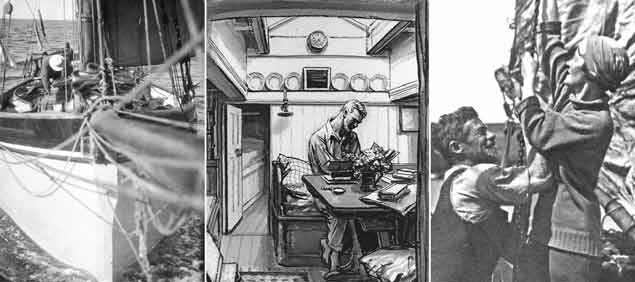

Despite the rugged challenge of her world-girdling voyage, Saoirse could provide homely comfort below – Conor O’Brien in the saloon as sketched by his wife Kitty Clausen in the 1930s

Despite the rugged challenge of her world-girdling voyage, Saoirse could provide homely comfort below – Conor O’Brien in the saloon as sketched by his wife Kitty Clausen in the 1930s

A proper little ship. The skylight as seen in previous photo has been faithfully re-created, while the traditional arrangements of the foredeck have come back to life. Photo: John Wolfe

A proper little ship. The skylight as seen in previous photo has been faithfully re-created, while the traditional arrangements of the foredeck have come back to life. Photo: John Wolfe

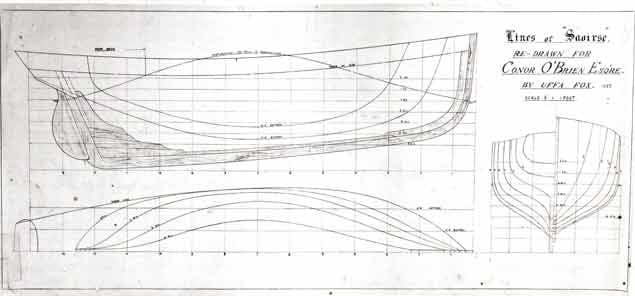

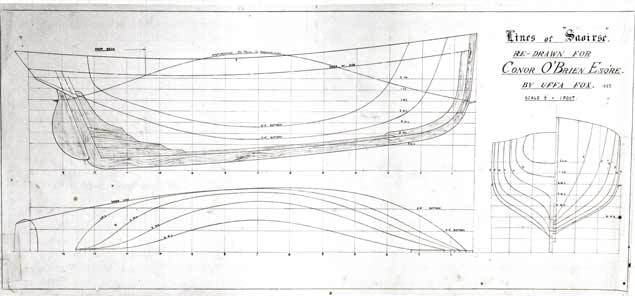

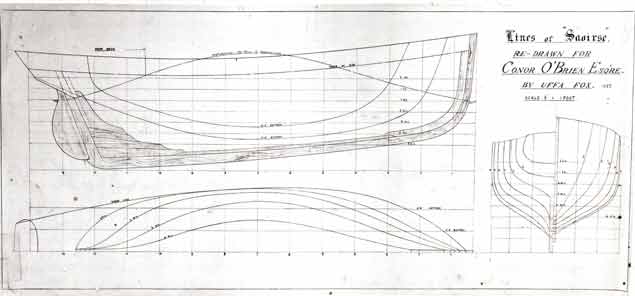

It’s a side-story to an already extraordinary saga, and in retrospect it seems inevitable that the Centenary would be greeted with the appearance of a Saoirse replica, for the original – or most of her – was lost in a hurricane in Jamaica in 1979. But while virtually all of the fabric of the first Saoirse was gone, Gary Mac Mahon of the Ilen Project in Limerick has a very comprehensive archive of Saoirse data and drawings, including a set of hull lines take off by Uffa Fox in Cowes in 1927.

Thus with an extensive additional set of Conor O’Brien drawings and many photographs, it was possible to contemplate an authentic re-build, and in time the project was under-written - and the new Saoirse’s ownership with it - by Fred Kinmonth, a high-flying international corporate lawyer who has made his career in Hong Kong but has retained strong family connections with West Cork, where he has been increasingly resident in recent years.

Happy at sea. Conor O’Brien relaxed on the helm as Saoirse makes knots in open water. With the raised after-deck, a special rail – “balustrade” almost - was fitted round the stern

Happy at sea. Conor O’Brien relaxed on the helm as Saoirse makes knots in open water. With the raised after-deck, a special rail – “balustrade” almost - was fitted round the stern

Newly afloat, the re-born Saoirse awaits the fitting of the special rail around the raised afterdeck. Photo: John Wolfe

Newly afloat, the re-born Saoirse awaits the fitting of the special rail around the raised afterdeck. Photo: John Wolfe

For as long as the new Saoirse was under construction in the Top Shed at Oldcourt - where Ilen had been restored before her – there was a spiritually soothing dimension to the project, as the highly atmospheric Top Shed - or the Old Grain Store or whatever you want to call it - has the capacity to be an almost sacred space when a wooden vessel is under traditional construction.

The sacred space. An early stage of construction for the new Saoirse in the unique atmosphere of the Top Shed at Oldcourt. Photo: W M Nixon

The sacred space. An early stage of construction for the new Saoirse in the unique atmosphere of the Top Shed at Oldcourt. Photo: W M Nixon

Yet inevitably the waypoint is approaching where the project would be better served by having the little ship afloat, and that occurred with Saoirse a few days ago. In one fell swoop, she went from being sheltered and cloistered, unable to view in all her totality in the confines of the shed, to a sudden state of total public display.

And she looks marvellous. Gallant. Jaunty. And saved from an unseemly dumpiness by the fact that master-builder Tom Moynihan in 1922 insisted on O’Brien adding an extra 2ft to the stern to provide a transom of robust elegance.

“A transom of robust elegance”. Conor O’Brien masterfully using a yuloh to propel the engine-less Saoirse across the harbour in Ibiza in 1932

“A transom of robust elegance”. Conor O’Brien masterfully using a yuloh to propel the engine-less Saoirse across the harbour in Ibiza in 1932

It is fascinating to compare the photos and plans from the original vessel with what we see now. The new ship has been built with such integrity by the Hegarty team that she is an artefact of significance in her own right. To that, we add her historic role. And it is a matter of note that the original was born in 1922, which also saw the birth of the Cruising Club of America. The founding Commodore of the CCA was Bill Nutting, who sailed across the Atlantic with his ketch Typhoon to get the blessing for his proposed club from Claud Worth, who in those days was the guru of world cruising, his thoughts on deep sea sailing seen as being in the realms of sacred scripture.

Thus in time, the definitive opinion on the world-girdling voyage of the Saoirse was given by Claud Worth in his Foreword to O’Brien’s classic book Across Three Oceans:

“Mr O’Brien’s plain seamanlike account is so modestly written that a casual reader might miss its full significance. But anyone who anything of the sea, following the course of the vessel day by day on the chart, will realize the good seamanship, vigilance and endurance required to drive this little bluff-bowed vessel, with her foul uncoppered bottom, at speeds from 150 to 170 miles a day, as well as the weight of wind and sea which must sometimes have been encountered…..however common ocean voyages in small yachts may become, Mr O’Brien will always be remembered for his voyage across the South Pacific and round the Horn.”

For sure, we all carry an image of Saoirse in our mind’s eye. And some of us can remember the original when she made her last visit to Ireland, on a voyage to Iceland in 1974. But it would take a heart of stone to be un-moved by this living vision which is now afloat in West Cork, the vibrant re-created reminder of an extraordinary voyage.

The voyage begins. Saoirse getting underway in Dun Laoghaire on June 20th 1923

The voyage begins. Saoirse getting underway in Dun Laoghaire on June 20th 1923

Irish Sailors, the Golden Globe & Cape Horn After 94 Years

On most coastlines in the world, you’ll invariably hear of some challenging nearby headland being referred to as “the local Cape Horn” writes W M Nixon

No other promontory worldwide has the same global image. It tells us much about the fearsome reputation of South America’s most southerly point, jutting as it does into the turbulent waters of the Great Southern Ocean where it becomes the Drake Passage, with Antarctica itself not so very far away across some of the roughest seas on the planet.

Cape Horn is always on the oceanic sailing agenda. And at the moment it is top of the list, with 73-year-old Jean-Luc van den Heede of France, leader in the Gold Globe Golden Jubilee Race, rounding it a week ago, while second-placed 41-year-old Dutchman Mark Slats (in a much-depleted fleet) will soon be there, albeit more than a thousand miles astern of van den Heede.

They and the remaining sailors in this challenging re-enactment are following in the wake of solo skipper Robin Knox-Johnston fifty years after he became the first man to sail round the world non-stop in Suhaili, with Knox-Johnston and his little ketch undoubtedly achieving one of world sailing’s truly great firsts.

One of world sailing’s most enduring images – Robin Knox-Johnston aboard Suhaili in 1969, approaching the conclusion of his non-stop global circumnavigation

One of world sailing’s most enduring images – Robin Knox-Johnston aboard Suhaili in 1969, approaching the conclusion of his non-stop global circumnavigation

But by the time Suhaili rounded Cape Horn on 17th January 1969, a number of small sailing boats had done so before her, though none in the same epic non-stop world-girdling style. However, some 45 years had elapsed since the first rounding of Cape Horn by a small cruising boat which had crossed the southern reaches of the South Pacific to get there. But though it was hailed afterwards as the great pioneering achievement it genuinely was, at the time those involved seemed to handle it in an almost low key way, however much it may have meant to them personally.

It was the evening of Tuesday, December 2nd 1924 (94 years ago this Sunday) when the small bluff-bowed 42ft gaff-rigged Irish ketch Saoirse, a craft of antique appearance, approached Cape Horn from the west. The weather had been unsettled with winds from several directions, and two days previously, squalls from the northeast had brought flurries of snow despite it being early in the southern summer. But conditions were improving as the Horn came abeam around 2200hrs in the last of the daylight.

Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse departing Dun Laoghaire for her global circumnavigation, June 20th 1923. She returned precisely two years later on June 20th 1925, after becoming the first small craft to run down her easting in the Great South Ocean from New Zealand to round Cape Horn. Photo: Irish Times

Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse departing Dun Laoghaire for her global circumnavigation, June 20th 1923. She returned precisely two years later on June 20th 1925, after becoming the first small craft to run down her easting in the Great South Ocean from New Zealand to round Cape Horn. Photo: Irish Times

With the onset of the short southern summer night with its brief darkness, the wind settled in the north, and the little ship made steady progress. By noon on Wednesday in fine conditions, she had made good 140 miles in 24 hours, aided by a favourable current of at least one knot. Superb visibility enabled the ketch’s crew to admire the massive scenery along the rugged coast as they shaped their course to pass eastward of Staten Island. The wind then drew fresh and favourably from the southwest, and despite progress being slowed by their vessel’s fouled bottom - for they had been at sea for more than 40 days since leaving New Zealand – by Saturday December 6th they were moored in Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands.

By being so far south in totally exposed waters, Cape Horn is often a huge challenge for small sailing craft

By being so far south in totally exposed waters, Cape Horn is often a huge challenge for small sailing craft

In rounding Cape Horn, the ketch’s amateur skipper Conor O’Brien (1880-1952) of Foynes Island on the Shannon Estuary had made the breakthrough towards becoming the first to take a small yacht around the world south of the Great Capes, running down his easting across the full width of the far Southern Pacific through everything that the Roaring Forties and Screaming Fifties could throw at him.

He faced it with some confidence, as his little vessel had successfully negotiated several ocean storms during her long passage from Dublin Bay. Ironically, it was in the warm and sunny latitudes of the Canary Islands that they had experienced one of their most severe tests, logging a day’s run of 185 miles while driving hard in rough seas in a sharp gale of the northeast trade winds.

Conor O’Brien was at his most content far at sea, helming Saoirse in markedly relaxed style. Although a “bluff-bowed little vessel”, as indicated here, Saoirse was well capable of good speeds with comfort

Conor O’Brien was at his most content far at sea, helming Saoirse in markedly relaxed style. Although a “bluff-bowed little vessel”, as indicated here, Saoirse was well capable of good speeds with comfort

But O’Brien’s own-designed little ship, soundly built by Tom Moynihan and his craftsmen at the Fisheries School in Baltimore in 1922, proved well able, and continued to log many excellent 24-hours runs. The most severe conditions were experienced between southern Africa and Australia, yet the ketch seemed to lead a charmed life. Although he and his shipmates observed several huge pinnacle breakers caused by intersecting wave patterns which he felt sure would have overwhelmed his vessel had she been caught up in one of those mega-breakers, it never happened, and the long haul across the southern Pacific to curve southward to round Cape Horn was subsequently recounted in an under-stated tone. But then, that was the style of the era and the milieu from which Conor O’Brien had emerged.

O’Brien may have been rewarded with a fairly gentle rounding of the Horn itself, but the very small world of ocean voyagers at the time had no doubt of the quality of his achievement. Although Joshua Slocum in Spray had negotiated his way westward from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the channels north of Cape Horn some 28 years earlier, the weather he’d experienced, coupled with the historical stories from the crews of much larger sailing ships which had succeeded in rounding the Horn – for many failed in the attempt – left no doubt about the extremely changeable and often ferocious conditions which were central to the challenge O’Brien had faced.

Conor O’Brien designed Saoirse himself, and while she was basically of old-fashioned style, she was way ahead of most boats of the time in having the galley well after in the area of least motion

Conor O’Brien designed Saoirse himself, and while she was basically of old-fashioned style, she was way ahead of most boats of the time in having the galley well after in the area of least motion

For circumnavigator sailors from Europe, once you’ve rounded Cape Horn and returned to Atlantic waters, there’s a reassuring feeling of being on the home stretch, for all that there are ten thousand miles still to sail. Certainly O’Brien and his crew of two became so relaxed that they spent six weeks in the Falklands over the Christmas period, becoming so much part of the local community that a crew-member married a local girl and much of Saoirse’s subsequent voyage northward through the Atlantic was made with just two on board.

Yet although it all continued to be done in a low key style, O’Brien was no slouch when publicity opportunities arose, and he returned to Dun Laoghaire on Saturday June 20th 1925 – two years to the day since he departed – in order to facilitate a rapturous welcome. Dublin Bay Sailing Club even cancelled their Saturday racing programme so that their members could join the fleet welcoming Saoirse home.

For most of the voyage, however, Saoirse and her crew were totally out of contact, and could get on with traversing the oceans in traditional lone ship style. And 45 years later, there were long periods in 1968-69 when Robin Knox-Johnston’s location with Suhaili was a matter of speculation rather than precision – it was something of a surprise when the battered but unbowed little ketch appeared in the distant approaches to Falmouth to claim an indisputable “first”.

But today, a constant flow of information in every shape and form is central to any major oceanic sailing event. The Golden Jubilee of the Golden Globe is supposed to be a retro event in which the participants sail old-style boats of closed hull profile using only the technology available in 1968. But the demands of the 21st century with its multiple communication technologies means that the outside world knows almost everything that is going on in this nine month saga.

Thus when Jean-Luc van den Heede had passed Cape Horn a week ago, it so happened that the AGM of the Old Cape Horners Association was being held in England’s historic naval harbour of Portsmouth, and they were provided with a radio linkup with the 73-year-old Frenchman who revealed that it was in fact his tenth rounding of the Horn, and his most recent visit had been during a cruise in the area when they’d landed at Cape Horn island’s semi-sheltered bay, and had gone visiting with the lighthouse keepers for all the world like cruisers of yore making their way along the west coast of Ireland or through the Hebrides.

Image of a great seaman – the 73-year-old Jean-Luc van den Heede. He has completed his tenth rounding of Cape Horn, leading the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee Race. On his ninth rounding, he was cruising, and he and his crew went ashore and visited the lighthouse keepersThis almost light-hearted approach to the realities of Cape Horn is classic van den Heede, for in order to still be in the lead in the Golden Globe, he had to survive a knockdown four weeks ago which was so violent that it caused the through-mast bolt supporting his lower shrouds to cut its way downwards through the mast extrusion, leaving the vital lower shrouds dangerously slack.

Image of a great seaman – the 73-year-old Jean-Luc van den Heede. He has completed his tenth rounding of Cape Horn, leading the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee Race. On his ninth rounding, he was cruising, and he and his crew went ashore and visited the lighthouse keepersThis almost light-hearted approach to the realities of Cape Horn is classic van den Heede, for in order to still be in the lead in the Golden Globe, he had to survive a knockdown four weeks ago which was so violent that it caused the through-mast bolt supporting his lower shrouds to cut its way downwards through the mast extrusion, leaving the vital lower shrouds dangerously slack.

For a while it looked as though he’d have to divert to Chile for repairs, but somehow this doughty veteran got aloft and cobbled together a repair which held together has now got him round Cape Horn and on to what is admittedly the longest homeward stretch in the world. But his performance is impaired, and he usually has three reefs in the main when only two would be needed were all the rig in full health.

Van den Heede’s Rustler 36 Malmut before the race – the problematic through-mast bolt and tang for the lower shrouds is visible below the lower spreaders

Van den Heede’s Rustler 36 Malmut before the race – the problematic through-mast bolt and tang for the lower shrouds is visible below the lower spreaders

This has meant that second-placed Mark Slats of The Netherlands has been closing the gap, but as van den Heede was an astonishing 1470 miles ahead when his rig damage occurred, Slats has to steadily outperform him by 20% in order to be first back to les Sables d’Olonne in 2019, and since van den Heede got into the Atlantic, the Slats rate of gain has slowed.

Race Tracker here

Both van den Heede and Slats are racing Rustler 36s, a slippy Holman & Pye designed sloop of 1980 which fits neatly into the retro requirement of being a 36ft production design of 1980 or earlier with the specified closed profile, even if in the Rustler 36’s case it does result in a transom stern with a very steeply sloping rudder and a propeller in a large aperture cut from the rudder, which must make them the very devil to handle under power in astern, or indeed under power in any confined manoeuvring situation under power, where prop thrust is often the key to doing the job.

Mark Slats’ Rustler 36 Ohpen Maverick with the steeply-raked ransom and sloping rudder much in evidence

Mark Slats’ Rustler 36 Ohpen Maverick with the steeply-raked ransom and sloping rudder much in evidence

This is probably not remotely of interest in the Great Southern ocean, but as Tim Goodbody so brilliantly revealed with his J/109 in Dublin Bay last weekend, a boat which has an easily-accessed stern-boarding system and handles confidently in astern under power is a very effective rescue machine in a man-overboard situation.

But that’s another topic to which we’ll return some day. Meanwhile, the reality was that the most popular design which turned up to start the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee was the Rustler 36, something of a surprise to casual observers as most folk had initially thought the response would be something nearer Suhaili, and ketch-rigged too.

But as it happens, the one Suhaili sister-ship which was allowed in under special dispensation, Abilash Tomy’s Thuriya from India, and one of the few other ketch-rigged boats, our own Gregor McGuckin’s Biscay 36 Hanley Energy Endurance, were both dismasted in September in the mother of all storms in the middle of the southern Indian Ocean.

Gregor McGuckin – he was dismasted after being rolled 360-degrees in an exceptional storm in an area of the Southern Indian Ocean where Conor O’Brien had noted the power of multi-directional cross seas to build freak waves

Gregor McGuckin – he was dismasted after being rolled 360-degrees in an exceptional storm in an area of the Southern Indian Ocean where Conor O’Brien had noted the power of multi-directional cross seas to build freak waves

Their skippers were successfully retrieved by a French Fisheries Patrol vessel while McGuckin was in the midst of an heroic effort to get to the seriously-injured Tomy under jury rig. But despite promises that Thuriya would be retrieved by the Indian Navy and restored to seagoing standard, she still seems to be out there and virtually not moving at all. This suggests that she is still lying to her broken rigging, whereas McGuckin’s boat is now nearly 400 miles away nearer Australia, as before his controlled retrieval and passage towards Tomy under jury rig, he succeeded in cutting adrift all the broken spars and rigging, and the former ketch has sometimes been drifting at 1 knot and more.

The experience of McGuckin and Abilash in that “perfect storm” is of added interest in that it happened in the area of ocean where Conor O’Brien saw his ultimate breaking crest. The wind strengths were nothing like the horrific power which assaulted Tomy and McGuckin, as at the time Saoirse was running in her surprisingly speedy style before “a moderate gale” (as they used to say), and O’Brien and his helmsman observed a large waving moving along with them maybe about a mile away.

There were marked cross seas running at the time – a significant factor recorded by Gregor McGuckin – and they went to work on this big wave until it peaked out like the Matterhorn or Mount Fuji, an absolutely extraordinary pinnacle of water which then collapsed in hundreds of thousands of tons of breakers and spume.

Neither O’Brien nor his shipmate said a word to each as this all-powerful force of nature manifested itself, but afterwards in his deck log he noted that had Saoirse been caught up in it, she and her crew would have instantly been goners. As for the professional seaman who’d been helmsman at the time, as soon as they reached port in Australia, he went ashore and wasn’t seen again. It greatly annoyed O’Brien, as this was the only helmsman other than O’Brien himself who had shown he could get Saoirse to perform to her best, and O’Brien had hoped that in due course the situation would arise where their combined efforts would see Saoirse achieve the 200 miles day’s run of which he was convinced she was capable.

Conor O’Brien as portrayed by his wife, the artist Kitty Clausen

Conor O’Brien as portrayed by his wife, the artist Kitty Clausen

He had many crew changes, but despite that and other difficulties, his underlying intention to sail home via Cape Horn was maintained. Ninety-four years ago on Sunday, it was achieved - a simple and beautiful historical fact of small craft ocean voyaging.

Today, the realities of the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee race underline the remarkable nature of what Conor O’Brien and Saoirse made into reality. He may not have been single-handed, but his crew of two were of limited experience, the boat was of extremely primitive type by today’s standards, and the elements of the unknown in what they were undertaking were beyond calculation.

Now that we know so much more about Cape Horn and the conditions which may be experienced in sailing past it, O’Brien’s feat with Saoirse in 1924 becomes that much greater. He may have died on Foynes Island in 1952, but Saoirse has lived on, and she is currently being re-built by Liam Hegarty at his Oldcourt Boatyard near her birthplace of Baltimore. In 2020, Saoirse will sail again, and we will wonder anew at the achievement of the great pioneering sailor of Limerick.

Saoirse being re-built in Oldcourt (left) and as she was in the 1930s after her global circumnavigation of 1923-25. Photos Gary MacMahon

Saoirse being re-built in Oldcourt (left) and as she was in the 1930s after her global circumnavigation of 1923-25. Photos Gary MacMahon

Conor O’Brien’s Historic Ketch Saoirse Re-emerges in West Cork

While the 56ft 1926-built restored ketch Ilen is a flurry of activity at Oldcourt near Baltimore in West Cork with the final stages of work before her re-launching late next month, in the Top Shed nearby where Conor O’Brien’s pioneering world-girdling Saoirse of 1922 is being re-built, there’s a more measured pace to the work writes W M Nixon

For this isn’t just any boat - Saoirse is something very special. Master shipwrights Liam Hegarty and Fachtna O’Sullivan and their team are putting all their skills into the re-build - working with plans taken off by Uffa Fox in 1927 - in order to provide commissioning owner Fred Kinmonth with a vessel which properly reflects the high regard in which Conor O’Brien’s circumnavigation of 1923-25 is held.

The photos show how the technology of 1922, and the skills of original boatbuilder Tom Moynihan, are being brought alive again in a setting which has for so long been associated with the restoration of Ilen. But once that larger ship had been taken out at the beginning of January to clear the way for Saoirse to be re-born, a new atmosphere began to prevail between the old stone walls, and the re-emergence of Saoirse, even if she is still at a very preliminary stage, is a wonder to behold.

Only the backbone is going to be part of the finished vessel, but the shape of Saoirse can be clearly discerned from the forms and battens now in place. Photo: Gary Mac Mahon

Only the backbone is going to be part of the finished vessel, but the shape of Saoirse can be clearly discerned from the forms and battens now in place. Photo: Gary Mac Mahon

More than ever, it brings a keen anticipation of sailing aboard a small vessel which punched way above her weight in setting some remarkable speeds in open water. Quite how she managed it is one of the reasons Uffa Fox was so keen to take off her lines when Conor O’Brien took her over to Cowes to do the Fastnet Race of 1927, the year after he’d sailed Ilen out to the Falklands.

This photo of Conor O’Brien in the first stage of the voyage, sailing the North Atlantic from Dun Laoghaire to Pernambuco in Brazil, tells us something of the secret of her unexpectedly high average speeds. They’re in the northeast trades probably in the region of the Canaries where they did the best day’s run of the entire voyage, clipping along in very fine style as the bow-wave and wake reveals. Yet the new little ship exudes an air of comfort, helped by the relaxed image projected by Conor O’Brien at the helm.

Saoirse at sea early in July 1923, on a maiden ocean voyage both for the ship and owner-skipper Conor O’Brien. On the helm, he is conspicuously relaxed in the knowledge that his new design performs exactly as intended

Saoirse at sea early in July 1923, on a maiden ocean voyage both for the ship and owner-skipper Conor O’Brien. On the helm, he is conspicuously relaxed in the knowledge that his new design performs exactly as intended

For by this stage, he knew his little ship – which he’d designed himself – was a winner on ocean sailing with sheets freed. We tend to take this knowledge for granted now. But what is forgotten is that when Saoirse departed from Dun Laoghaire with much fanfare on June 20th 1923, neither she nor her owner had ever completed an ocean sailing voyage.

Yet now, here is O’Brien savouring the fruits of his creative labour, and he does it with style. Far from being attired in rugged seafaring gear, he’s dressed as though he’s on his way to an informal and convivial lunch at some friendly country house, followed perhaps by some mildly tipsy tennis. That summery shirt, collar spread wide, together with the tweed jacket, speak of everything except being at sea and sailing quite fast.

However, if we look more closely, we note that his tweed jacket’s left arm - draped nonchalantly along the taffrail - is soaking wet. A playful wave of the sea has decided that he can’t be allowed to get away with this performance without something happening. But with the camera out, O’Brien is determined to play it for all its worth, and the image of a pioneering ocean voyager without a care in the world is beautifully captured.

In recent weeks, much of the attention on the traditional boat-building Mecca of Oldcourt in West Cork has been focused around the complex moves involved in vacating the 56ft ketch Ilen from the boat-building shed writes W M Nixon. This meant safely re-locating her through the very crowded boatyard to a secure commissioning berth where a sheltering tent could be erected to allow the fitting-out work to proceed whatever the weather.

Then in time, while fitting the interior has been proceeding, there followed the “blind stepping” of the two masts which had been trucked down from the Ilen Boat-Building School in Limerick, where the massive spars and rig had been built and pre-assembled.

“We have a shape – we have the shape.” In boat-building terms, putting the moulds in place is just part of the process, but for the casual observer it gives a first vivid impression of what the re-built Saoirse will look like. Photo: Gary MacMahon

“We have a shape – we have the shape.” In boat-building terms, putting the moulds in place is just part of the process, but for the casual observer it gives a first vivid impression of what the re-built Saoirse will look like. Photo: Gary MacMahon

After restoring the Ilen at Oldcourt, the first stages in re-building Saoirse in the same shed provide the clearest message that a 42-footer is very much smaller than a 56-footer, yet it was the 42-footer that sailed round the world. Photo: Gary MacMahon

After restoring the Ilen at Oldcourt, the first stages in re-building Saoirse in the same shed provide the clearest message that a 42-footer is very much smaller than a 56-footer, yet it was the 42-footer that sailed round the world. Photo: Gary MacMahon

All this has been safely dealt with despite some periods of freakishly bad weather. But it had to be done on time, as the shed was needed because it had been agreed to start work in January on the re-build of Conor O’Brien’s 1922-built 42ft Saoirse. This project – for experienced sailor Fred Kinmonth of Hong Kong – will be in honour of Saoirse’s great achievement of 1923-25, the first global circumnavigation of the world by a cruising yacht south of the Great Capes.

So while much attention has been on the brightly-painted Ilen and the flurry of activity around her, in the shed shipwrights Liam Hegarty and Fachtna O’Sullivan and their team have been left in relative peace for the key initial stage of creating Saoirse’s backbone from various very substantial pieces of carefully-selected oak.

Saoirse’s backbone could only begin to come together thanks to a complex process for sourcing suitable oak. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s backbone could only begin to come together thanks to a complex process for sourcing suitable oak. Photo: Gary MacMahon

But as Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Project puts it: “In taking on a job like this, you have to create a new supply chain. There is no line of supply for traditional boat-building on this scale, and we had to make our own way in finding pieces of sound oak which would help to provide the myriad of shapes from which the backbone and the frames will eventually be created”.

The upshot was that if a great oak came down anywhere in Munster, they’d soon be on the spot to see if anything usable could be salvaged from it. And even then, after the processes of seasoning and so forth, that was only the beginning of the job. A piece of oak might be worked on until it was nearly ready to be installed in the backbone, but then some aspect of the almost-finished section would give out the wrong messages, and it would be discarded and an alternative piece sought from the stockpile.

Saoirse may be significantly smaller than Ilen, but renewing her backbone has involved working with substantial pieces of oak, some of which didn’t pass the final test. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Saoirse may be significantly smaller than Ilen, but renewing her backbone has involved working with substantial pieces of oak, some of which didn’t pass the final test. Photo: Gary MacMahon

So it was patient, painstaking work, it took time, and it was best done in peace and private. But finally the makings of the backbone were in place, and there then could be visible progress – the erection on the keel, from stem to stern, of the temporary moulds which would show precisely the ultimate shape of Saoirse’s frames.

This has been taking place during the past week, and though it’s essentially a mock-up, just an integral part of the building process, nevertheless it feels as though the project has taken a mighty leap forward. And as with everything to do with Saoirse, it’s redolent with history.

Saoirse’s sternpost – Tom Moynihan insisted on lengthening the counter beyond Conor O’Brien’s hyper-economical original design. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s sternpost – Tom Moynihan insisted on lengthening the counter beyond Conor O’Brien’s hyper-economical original design. Photo: Gary MacMahon

While Conor O’Brien of Foynes and Tom Moynihan of Baltimore may have sketched out Saoirse’s lines (with Moynihan insisting the inelegantly short stern be lengthened a little), their drawings were only very rudimentary. But after the great voyage, Saoirse was famous. When Conor O’Brien took her to Cowes to do the 1927 Fastnet Race, the already-legendary Cowes-based designer Uffa Fox took off the boat’s lines.

As was right and proper, the lines sketched by O’Brien and Moynihan were remarkably close to the little ship as she was finished. But it was the lines as taken off by Uffa Fox which have been used in the process whereby the moulds have been assembled and erected, and this has been a speedy process which by Friday night was providing a vision of Saoirse which has an air of reality to it.

At the end of 2017, it was still a project in planning. But now, we’re already seeing something. The dream is becoming reality.

Saoirse’s lines as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes in 1927

Saoirse’s lines as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes in 1927

Saoirse sailing in Cornish waters during the 1950s while in the ownership of the Ruck family. Photo courtesy Gary MacMahon

Saoirse sailing in Cornish waters during the 1950s while in the ownership of the Ruck family. Photo courtesy Gary MacMahon

Historic Ketch Saoirse’s Re-birth Starts to Take Shape

West Cork may have the image of an easy-going paradise where life proceeds at a leisurely pace writes W M Nixon. And maybe that is indeed the case in summer, when there are more people around determined to keep things gentle and slow.

But it seems that by contrast, in winter it’s all bustle and productivity. As regular readers of Afloat.ie will be aware, while the rest of us were snuggling down to get through the depths of the festive season with occasional bursts of good news from the Irish-dominated Sydney-Hobart Race as our only contact with the world of sailing, down in West Cork around Liam Hegarty’s boatyard at Oldcourt there was a flurry of activity when conditions suited.

These bursts of skilled co-ordinated work were to take advantage of the brief daylight and narrow weather windows for the delicate job of moving the 30-ton newly-restored trading ketch Ilen. The 1926-built 56ft vessel had to vacate the building shed in order to provide space for work to begin in January on the re-building of Conor O’Brien’s historic world-girdling 42ft ketch Saoirse, built in Baltimore in 1922, and by 1925 a global circumnavigation veteran and pioneer of the challenging route south of the Great Capes.

The lines of Saoirse as taken off by the international designer Uffa Fox at Cowes in 1927

The lines of Saoirse as taken off by the international designer Uffa Fox at Cowes in 1927

Who could have believed we’d ever see it happen? Ninety-one years after the lines were recorded by Uffa Fox, Saoirse is being re-built in Oldcourt. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Who could have believed we’d ever see it happen? Ninety-one years after the lines were recorded by Uffa Fox, Saoirse is being re-built in Oldcourt. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Although Conor O’Brien’s subsequent writings on seamanship and the special demands of ocean voyaging were influential, he was directly involved in the design and of building only two vessels, Saoirse in 1922 and the Falkland Islands trading ketch Ilen in 1926. Both were built in the Fisheries School boatyard in Baltimore in West Cork under the direction of Tom Moynihan. And if Conor O’Brien was listed as the designer, nevertheless Tom Moynihan was known to have improved on O’Brien’s ideas when he thought it necessary.

But while Baltimore was where the two ocean-going craft were built, O’Brien himself was very much a sailor of the Shannon Estuary. His family were associated with the lands along the south shore of that mighty waterway, and with Limerick city itself. Yet there were many in Limerick – and throughout Ireland too – who felt that Conor O’Brien never really received the recognition he deserved in his own country.

Many may have thought it, but only one took action. Twenty-one years ago a young Limerick man, Gary MacMahon, decided that the best way to begin to remedy the situation was to bring the recently-retired Ilen home from the Falklands to Ireland for a full restoration.

It says everything for Gary MacMahon’s dogged persistence that despite a lack of practical official interest in Ireland – other than some general goodwill - not only has Ilen now been restored, but in Limerick the Ilen Project has spawned a successful city-based boat-building school. This has links to international artisan boat-building networks, while at the same time working a successful co-ordination with the Oldcourt boatyard for the Ilen restoration.

The profile of Saoirse’s distinctive stern re-appears – Tom Moynihan and his men ensured that her appearance was improved by a short counter stern, which was not originally envisaged by Conor O’Brien Photo: Gary MacMahon

The profile of Saoirse’s distinctive stern re-appears – Tom Moynihan and his men ensured that her appearance was improved by a short counter stern, which was not originally envisaged by Conor O’Brien Photo: Gary MacMahon

Meanwhile, as all this was steadily developing, MacMahon was continuing to enlarge his substantial Conor O’Brien archive, and always in the background there was the idea that Saoirse herself could be re-born. A widely-accepted narrative had it that she had come ashore to destruction on Negril Beach in Jamaica in 1979 in the aftermath of a hurricane. But until he had actually visited the area and talked with locals himself, Gary MacMahon had an open mind on whether or not enough of Saoirse still existed for a re-build.

His hunch proved sound. An extended visit to Negril and relevant areas of Jamaica in July 2015 provided both significant parts of Saoirse herself, and sufficient documentation to ensure that any project would be recognised as a re-building.

It had been a couple of months earlier, at the Baltimore Woodenboat Festival in May 2015, that Gary MacMahon and Liam Hegarty had found they both passionately believed to the point of total agreement that Saoirse should be re-built to become a full sea-going vessel again. As to the means to do it, at that time it was a matter of faith. But as they had already found sources of good timber for the restoration of Ilen, they also began ordering wood which could be used in a re-building of Saoirse.

It was all still a vague and benevolent notion in the background of the Ilen project until, in September 2016, noted Hong Kong-based sailor Fred Kinmonth stepped into the old shed where Ilen was being restored, and the entire project took on a fresh direction. There are special Kinmonth family connections to West Cork, and in due course, Fred Kinmonth confirmed that he wished to support the re-building of Saoirse as a two year project, beginning January 2018.

It was a decision both inspiring and demanding. It set a deadline. And like all deadlines for worthwhile projects, it was close enough in the end, but it was met. By January 2018, Ilen was gone from The Old Grainstore to a new berth in the yard where her commissioning continues, while in the shed the space was cleared and re-organised, and now Liam Hegarty’s team, with master shipwright Fachtna O’Sullivan the most experienced, have already created the basis of the backbone for re-building Saoirse.

Saoirse’s forefoot re-emerges, both in massive timber and as a template. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s forefoot re-emerges, both in massive timber and as a template. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The atmosphere is almost reverential, for it’s very seldom that such a remote dream can be brought to fulfillment in the one place where it can be validly created. In time, the re-building of Saoirse will develop its own routine, and the colourful camaraderie of the top shed will brighten the work on its way. But for now, in the first weeks of this very special project, we’re at the serious stage where everything has to be just right. For the time being anyway, the open-door policy is no longer operational - the days of anyone just dropping in and hoping to engage the team in friendly chat are on hold. There is only one genuine opportunity to re-build the Saoirse. This is it. It’s a serious business.

Ireland’s Pioneering World-Girdler Saoirse Will Sail Again

Work began this week at Oldcourt near Baltimore in West Cork on reconstructing Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse. One of the most remarkable sailing vessels in Irish and world maritime history, the 42ft Saoirse is unique in many ways. W M Nixon gives some of the background to a complex story.

The early 1920s in Ireland are generally remembered as a time of extreme turmoil, with a War of Independence, the establishment of the Irish Free State with Northern Ireland partitioned, and a Civil War which was followed by a restless period as the fledgling State developed its new identity.

Yet in this uneasy time of frequent disruption, in Baltimore in West Cork a special boat, a proper little ship, was built in 1922 to become an ocean voyager which provided a vision of a more peaceful time for a world still only slowly recovering from the horrors of World War I in 1914-1918.

This unique sailing ship was also a maritime inspiration for the new Ireland, uncertain of itself in an uncertain world. For this was Conor O’Brien’s characterful 42ft ketch Saoirse, which he designed himself, and with which - between 1923 and 1925 – he pioneered the round the world route south of the Great Capes, an ocean voyaging “first” which was forever written into world sailing history.

The scale of Conor O’Brien’s achievement at the time is difficult for us to grasp today, when we are aware that the Great Southern Ocean, which runs unhindered round the globe and regularly generates extreme storms, can indeed be navigated by relatively small craft, albeit with the strongest of construction, the best of equipment, and experienced crews.

But in the early 1920s, it had a completely fearsome reputation, and rounding Cape Horn was a venture undertaken only by the most capable and usually very large sailing ships, or the most powerful steamers. So when the little Saoirse rounded the Horn from New Zealand in the last of the daylight on Tuesday December 2nd 1924, it was a pioneering achievement for everything which has come since, including the Golden Globe, the Whitbread Race, and the Volvo Ocean Race.

Saoirse departs from Dun Laoghaire, June 20th 1923. Photo: Irish Times

Saoirse departs from Dun Laoghaire, June 20th 1923. Photo: Irish Times

In Ireland, the greatness of what Conor O’Brien and Saoirse had done was recognized at the time, and his departure from Dun Laoghaire on June 20th 1923 was well celebrated and reported in the Dublin newspapers. Accounts of some aspects of the voyage then appeared in the press in Ireland during its progress, and Saoirse was welcomed back to Dun Laoghaire afloat by Dublin Bay Sailing Club cancelling its racing for the day to provide an escorting fleet, and ashore by a crowd of at least ten thousand, followed by a ceremonial parade into the city with the day concluding with a gala dinner.

After that, O’Brien was busy with writing the story of the voyage for what was to be a popular book, Across Three Oceans, and seeing through the fulfillment of a contract for the construction of a larger version of Saoirse to be the inter-islands communications vessel for the Falkland Islands, for the islanders there had been much impressed by the little ship’s sea-keeping power when she came into port with Cape Horn successfully astern.

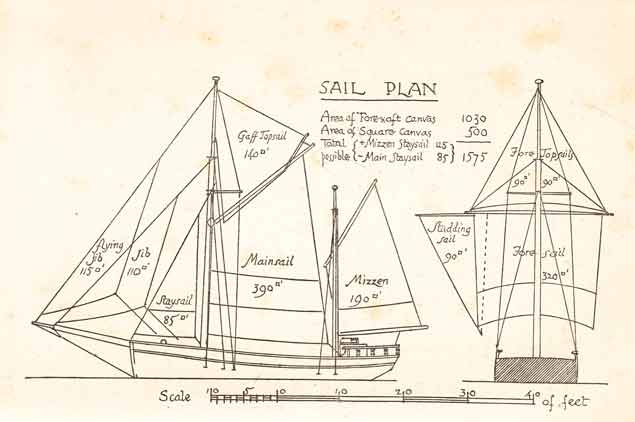

Good weather at sea, and time to set Saoirse’s stu’nsails. The ability to use squaresails was fundamental to OBrien’s design concept.

Good weather at sea, and time to set Saoirse’s stu’nsails. The ability to use squaresails was fundamental to OBrien’s design concept.

The 56ft ketch Ilen was the result of this, and O’Brien – crewed by Cape Clear men Con and Denis Cadogan – sailed her out to the Falklands in 1926 from his home port of Foynes in the Shannon Estuary. For although his boats were built in Baltimore by Tom Moynihan and his team at the boatyard attached to the Fisheries School, the O’Brien ancestral lands were along the south shore of the Shannon Estuary, while his first steps afloat were at Foynes, though he also learned sailing at Derrynane in West Kerry where the family took summer holidays. But from 1914 onwards, as the effects of Land League and other factors diminished the family estate, Foynes Island was both his home and his home port in Ireland.

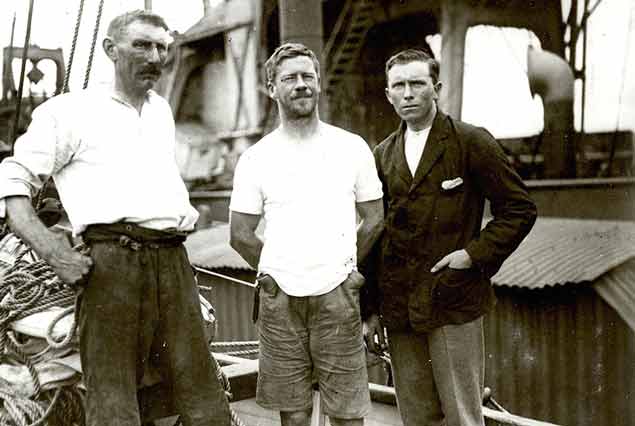

Conor O’Brien (centre) with Con and Denis Cadogan of Cape Clear, who sailed the Ilen with him out to the Falklands.

Conor O’Brien (centre) with Con and Denis Cadogan of Cape Clear, who sailed the Ilen with him out to the Falklands.

However, with the publication of Across Three Oceans and the completion of the Ilen contract, his diminishing income was temporarily boosted, and 1927 was celebrated with the ketch-rigged Saoirse being given a rather spectacular new rig which, despite the same masts being retained, made her look like something of a small brigantine, and with this O’Brien set out to do the Fastnet Race.

This meant he spent some time in Cowes beforehand, where he was much feted, with the legendary designer Uffa Fox taking off Saoirse’s lines. For although she was rightly described as “a bluff-bowed little boat”, by the standards of the day she had achieved some formidable 24-hour runs during her circumnavigation, and Uffa Fox was determined to see if he could find some special secret to her shape to explain the high average speeds.

Why did she sail so well? Saoirse’s world-girdling sailplan as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes, 1927. The lightly-sketched squaresails were the secret of her steady downwind speed

Why did she sail so well? Saoirse’s world-girdling sailplan as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes, 1927. The lightly-sketched squaresails were the secret of her steady downwind speed

Saoirse’s hull lines as taken off by Uffa Fox.

Saoirse’s hull lines as taken off by Uffa Fox.

Saoirse during the 1927 Fastnet Race. Buoyed up with fresh income, Conor O’Brien gave her rig a new look, but it still uses the same masts.

Saoirse during the 1927 Fastnet Race. Buoyed up with fresh income, Conor O’Brien gave her rig a new look, but it still uses the same masts.

But the secret was Conor O’Brien himself. Although the Fastnet Race was dismal for Saoirse as it involved much windward work, off the wind with his nerves of steel he was able to drive his peculiar little ship well beyond her theoretical limit. Yet he almost always brought her to port in one piece, and his judgment of what was possible was renowned.

From this you might expect a stern steady silent type, but Conor O’Brien (1880-1952) was a man of many talents and a mass of contradictions. Short-tempered, sometimes voluble to excess, he expected too much of crews who were sometimes casually recruited, and in all he may have had as many as 17 different people crewing with him during Saoirse’s circumnavigation.

Away from his sailing, his life sometimes seemed aimless. Reared largely in England though holidaying in family properties in Ireland in the summer, following some changes of direction he finally qualified as an architect, and after 1903 he lived for some years in Dublin. Mountaineering was his main outdoor activity, but soon he was further into sailing, and by 1910 he’d bought the hefty cutter Kelpie which he modified for cruising with conversion to a ketch.

Another interest was support of Home Rule for Ireland, and in July 1914, Kelpie joined Erskine Childers’ Asgard in going to collect the arms for the Irish Volunteers from a rendezvous at the Ruytigen Lightship off the Belgian coast. While Asgard’s consignment of Mauser rifles was spectacularly landed in broad daylight in Howth on July 26th, the Kelpie’s cargo was brought ashore at night a few days later at Kilcoole in County Wicklow, having been trans-shipped to the auxiliary yacht Chotah, owned by another distinguished sailing man with direct Limerick connections, the surgeon Sir Thomas Myles.

Within a very few days, the entire scene changed with the outbreak of the Great War, and most of the leading gun-runners were to serve with the British forces. Despite his Home Rule enthusiasm, O’Brien had since 1910 been a member of the Royal Naval Reserve, which had given him useful training for his growing involvement in sailing. Between 1914 and 1918, it provided him with sometimes uneven war experience, for his temperament was much more suited to small unit action than anything involving significant numbers in some sort of organised form.

Post war, he returned to an Ireland which since the 1916 Easter Rising was moving inexorably towards independence and inevitably towards partition. When a unofficial Independent Provisional Government was set up in 1919 in a sort of parallel universe functioning effectively in opposition to British rule from Dublin castle, he offered his services to it with the Kelpie, and was a seaborn Fisheries Inspector for this alternative administation on the West Coast in the summer of 1920.

The situation was confused, to say the least, and in 1921 he went off cruising to Scotland single-handed, with some mountaineering planned in Skye. Returning alone through the North Channel and slowly beating to windward at night, he slept through the ringing of an alarm clock, and the heavy Kelpie came ashore in the foggy dark, well stuck on rocks near Portpatrick on the Scottish coast, and slowly but inevitably became a total loss.

O’Brien appeared out of the morning mist into Portpatrick Harbour, rowing in his little dinghy with all that remained of his worldly possessions about him, for he had sold his house in Dublin, and all he had for home was the use of a family cottage on Foynes Island.

As he recovered both there and with family in Dublin from his ordeal – typically blaming the alarm clock – he started finalizing the designs of an ocean-going voyager. For although he had no personal experience of long sea voyages under sail in a small yacht, he had long wished to do so, but had known the Kelpie was far from ideal for such ventures. What he wanted was a boat of simple ketch rig capable of setting proper square sails for long runs in the Trade Winds.

Saoirse’s plans as drawn by Conor O’Brien for his book Across Three Oceans – the short counter stern was an addition insisted on by the boatbulders of Baltimore.

Saoirse’s plans as drawn by Conor O’Brien for his book Across Three Oceans – the short counter stern was an addition insisted on by the boatbulders of Baltimore.