Displaying items by tag: Peel

Portaferry and Peel RNLI came to the aid of a kayaker who got into difficulty in the Irish Sea earlier this week.

The man, who had been kayaking from the Isle of Man to Northern Ireland from early morning on Wednesday (8 June) became fatigued and, when he couldn’t see land, raised the alarm for help.

Both the inshore lifeboat from Portaferry RNLI and the all-weather lifeboat from Peel RNLI on Mann were requested to launch.

The pagers at Portaferry RNLI sounded shortly after 5pm as the station’s operational and fundraising volunteers were enjoying a visit by the RNLI’s chief executive Mark Dowie.

The inshore lifeboat, helmed by Chris Adair and with three crew onboard, launched immediately and made its way to the scene some 14 miles out from the Strangford Narrows. The Irish Coast Guard’s Dublin-based helicopter Rescue 116 was also tasked.

Weather conditions at the time were drizzly but there was good visibility. The sea was calm and there was a Force 3 easterly wind blowing. Once on scene at 5.58pm, the crew faced a Force 4 wind, fair visibility and a rough sea state.

The volunteer crew assessed the situation before helping the casualty out of his kayak and bringing him onboard the lifeboat.

He was then transferred to Peel RNLI’s all-weather lifeboat where he was brought inside the wheelhouse to be warmed up.

Both Portaferry and Peel lifeboat crews made their way to Portaferry with the casualty, who was checked over to ensure he was safe and well before he got warmed up with pizza and tea at the station.

Speaking following the callout, Philip Johnston, Portaferry RNLI lifeboat operations manager said: “The casualty was wearing the appropriate gear for kayaking and made the right decision to call the coastguard for help once he found the conditions too much.

“We would like to wish him well and thank our fellow volunteers from Peel and our colleagues in the coastguard who were also on scene.

“The pagers went off as our volunteers were having a meeting with Mark Dowie, our chief executive who was visiting from England. We were delighted to update him on our lifesaving work at Portaferry RNLI and were equally delighted to be brought up to speed from him on the various work that is happening across our charity that we are all so passionate about.

“As the pagers went off, Mark commented that out of the 124 stations that he has visited so far, we were the fourth station to have a call out during his visit.”

Dramatic Rescue Of NI Trawler In Irish Sea Off Isle Of Man

#RNLI - Two British naval war ships, three helicopters and a fishing vessel joined Peel RNLI in the dramatic rescue of a trawler between Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man in the early hours of Wednesday morning (21 September).

The 20m converted fishing vessel from Kilkeel in Co Down was on passage in the Irish Sea from Glasgow to Conwy in Wales when it started taking water through the stern tube and was in danger of sinking some 11 miles west of the Isle of Man.

Peel's all-weather lifeboat Ruby Clery, under the command of coxswain Paul Cain, launched shortly after the volunteer crew were alerted at 1.30am.

Northern Irish fishing vessel Stephanie M gave shelter to the casualty until the lifeboat crew were able to put a pump on board to evacuate the water.

The vessel, with three adults and one child on board, was soon stabilised and helicopters and other vessels stood down. The trawler was then taken in tow by the lifeboat bound for Peel.

During this time, a young woman and the child were taken ill, so the tow was dropped about 15 minutes from Peel and the two taken to a waiting ambulance where they were treated and then removed to Nobles Hospital.

Meanwhile, the lifeboat returned to the stricken vessel, which was now under its own power, and escorted it into Peel Harbour at about 5am.

"We advise people to always check their equipment before leaving port," said Cain after the callout.

Traditional Boats of Peel, Isle of Man Do The Business

The Peel Traditional Boat Weekend at the hospitable port on the west coast of the Isle of Man has been developing steadily since its inception in 1991. Located in the middle of the Irish Sea, the Peel gathering has become a magnet for boat enthusiasts of all kinds from Ireland, Wales, England and Scotland. W M Nixon sampled it for the first time in August 2013, and found that it deserves its hospitable reputation.

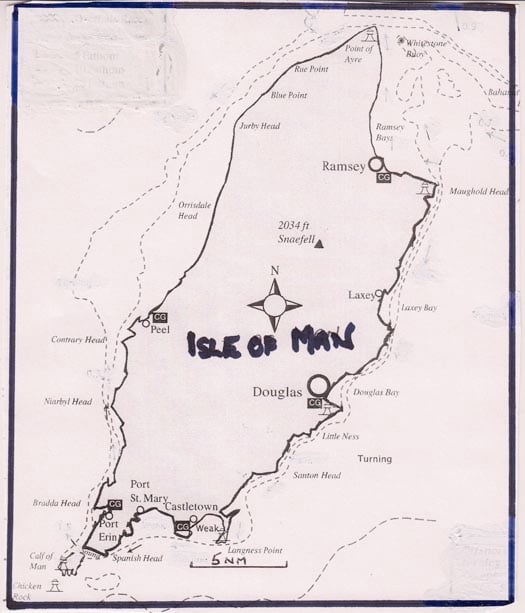

#peel – Cruising around the Isle of Man is dictated by its extraordinary tides. We may not be talking of the exceptional ranges of the Bay of Fundy, but you're right up with the North Coast of Brittany in the island's huge rise and fall. As for the ports, there are only two which have been fitted with automatic gate flaps that retain enough water in their harbours for civilised berthing at marina pontoons when the tide has receded.

These are the island's capital of Douglas on the east coast, and the ancient fishing stronghold of Peel on the west. At other ports such as Ramsey, Laxey and Castletown, you have to be prepared to dry out alongside. There are anchorages of sorts available at the main sailing centre of Port St Mary on the south coast (where it is also possible to lie afloat alongside at low water, but it's an unbelievably long way down), at Derbyhaven in behind the island's southeast corner of Langness, and at Port Erin towards the southwest corner, but they don't really provide the restful berths which cruising folk hope to find at the end of a day's sail.

We'd hoped to round out our two year sailing celebration of the centenary of Dickie Gomes' 36ft yawl J B Kearney Ainmara by an easygoing circuit cruise of the Isle of Man (the old girl won the Round Isle of Man Race in 1964, when she was but a stripling of fifty-two summers), and conclude it with participation in the Peel Traditional Boat Weekend 2013, in its turn the concluding event in the Irish Sea of the Golden Jubilee celebrations of the Old Gaffers Association, in which we'd already been much involved in Dublin and Belfast. But it was a programme which just couldn't be made to integrate.

While the Isle of Man would be attractive to cruise round if the harbours at Ramsey, Castletown and Port St Mary provided floating berths, the fact that only Peel and Douglas have marinas enclosed within gate flaps makes it very tempting to keep your boat at one of these two ports, and see the rest of the island by other means.

Though I haven't seen it stated in any relevant cruising directions (perhaps because it's so bleeding obvious), the sensible time for a three or four day cruise around the Isle of Man is when high water is morning and evening. That means you can arrive off your chosen port for the night at a civilised hour, and go in immediately. Even if you've had to dry out overnight, you can still depart at your leisure in the morning on the new tide, and though you may have to push tidal streams to the next port, the tides are much smaller when high water is morning and evening rather than noon and midnight, so you have a chance of overcoming any adverse streams. Then too, the weaker tide means there's less likelihood of rough water, which in certain areas of the Isle of Man is something of a speciality.

But the format of the Peel Traditional Boat Weekend scuppered this fine plan of a leisurely island circuit. The Weekend is staged when high water is pushing towards lunchtime, as the waterborne highlights of what is really a five day boatfest are Parades of Sail on the Friday and the Sunday. On those days, everyone is expected to head seawards just as soon as the automatic gate flap goes down, then they tear around on the Irish Sea for a couple of hours with all sail set, showing off big time, and then they scuttle back into port before the gate comes up again.

It works very well, but it means that you're totally Peel-focused for the berthing of your boat while the festival is in full swing. So we reckoned the only solution was to give in gracefully. Ainmara secured a marina berth handily off the Creek Inn, and there we were every night from Wednesday August 7th until Sunday August 11th, absorbing Manx culture by the bucket-load, and taking on board nautical ideas, rig designs, and boat layouts of every imaginable type, plus a few totally unimaginable as well.

Ainmara manoeuvring into her convenient berth in Peel Marina off the Creek Inn. Photo: W M Nixon

High summer in the Isle of Man. Looking seaward down the inner harbour at Peel towards the castle. Photo: W M Nixon

It was the ideal scenario for a plague-like outbreak of harbour rot, but as already reported here on August 24th, we made an immediate point of visiting the world's oldest yacht, at her abode in the characterful old port of Castletown before contemplating anything else. And then between the jig and the reels we saw a lot of this fascinating island by many different means of transport, only drawing the line at the ancient tram which runs between Douglas and Ramsey, because even for the most easy-going cruising man, it is just too slow.

Perhaps it's there to offset a central part of Manx culture, the TT motorcycle jamboree. The tram may well be a deliberate reminder of the slow and safe life, but the TT is all about fast and dangerous, and it's almost a religious cult. With the quaint little winding roads, the Isle of Man is probably the only place in the world where the tourism authorities will object if the road engineers want to straighten out a particularly dangerous corner.

One of our ship's complement of three, Brian Law, is a mad keen biker, so he really was in seventh heaven, but we kept him grounded with more sedate ways of travel such as the little old very smoky narrow gauge steam railway which runs from Douglas eventually to Port Erin - and don't forget to start your journey with the fireman's breakfast off a shovel in Douglas station.

The only way to start the journey – the Fireman's Breakfast in Douglas Station, served on a shovel. Photo: W M Nixon

The Peel to Port Erin Express. Needless to say, each vintage compartment had a No Smoking sign. Photo: W M Nixon

But having done the island from end to end, the crew of Ainmara would like it to be known that the best way to cruise the Isle of Man is up front on top of a double-decker bus. Much of the island scenery is a sort of miniaturised Ireland or Scotland, so at first it seems completely bizarre that urban double-deckers run on many of the routes. And up top, it has to be admitted that at times the old bus gets a mighty wallop from a tree branch. But the views are marvellous, you get to meet a fascinating array of the locals, the bus will take you scenically to an extraordinary variety of towns and villages, and at day's end you return to Peel, the most characterful place of all, and there sits your boat serenely off the inn, and the party just getting going. It's cruising perfection.

And for anyone into traditional or classic or just interesting boats, Peel is paradise. We'd got the flavour of it as we'd arrived in the sunshine of a perfect summer's day on the Wednesday, going through the narrow entrance with Mike Clark's Manx nobby White Heather – traditionally rigged with huge lug mainsail – to starboard, while to port beside the harbour office was the superbly restored varnished Ray Hunt-designed 57ft Drumbeat, originally built for Max Aitken with twin centreboards – one for each tack – back in 1957, and newly arrived as an Isle of Man resident after her second total restoration.

Mike Clark's restored Manx nobby White Heather sets the classic lug rig.

The superstar of 1957. The restored Drumbeat with her varnished hull is a new resident of the Isle of Man. This view is looking seaward towards the Outer Breakwater over the footbridge and gate flap at the entrance to Peel Inner Harbour with its marina. Photo: W M Nixon

Peel's marina has revitalised this former fishing port. Photo: W M Nixon

Peel has always had something special, and since it got its gate flap in 2005 and the 124-berth marina three years later, the harbour area has been on the up and up, and the maritime community spirit in the town is a real tonic. We got our first taste of it that night in the Peel Sailing and Cruising Club where there was a merry buzz and a sense of anticipation with greetings for many old friends already there, and more on the way with the clubhouse affording a fine view of the outer breakwater, above which the upper rigs of gaffers could be seen as they headed for port in the last of the evening light, providing an entertaining guessing game as to which boat would be revealed as they swept past the outer end.

In the morning the harbour was sunlit and lively with more boats which had come in on the midnight tide. We finalised our entry and found that as were to do our duty by making a holy show of ourselves during the Parades of Sail for the delectation of the public, our hosts in turn would feed and water us in port, with the makings of breakfast put aboard each morning, and a fine feed for all crews each night in the Masonic Hall, the only place in Peel big enough to cater for the crowd.

All this hospitality at the Peel Traditional Boat Weekend involved many people and several organizations with a raft of sponsors, so it was a bit difficult to keep track, but as the two days of sport afloat had their timing dictated by the opening of the gate-flap, it was literally a case of going with the flow and enjoying yourself.

The basics of the weekend's administration were provided by Mike Clark of the traditional Manx Nobby White Heather and his PL 2013 team, but while they with their access to the Masonic Hall had the space for the crowd scenes, Andy Hall the Commodore of Peel S & Cr C and his many volunteers provided an additional key focal point in their fine clubhouse. So we'd all these delightful folk making a massive and very effective voluntary input to our enjoyment, and that was before we acknowledged the contribution of the top honchos of the various Old Gaffer Associations from all round the Irish Sea.

Mike Clark of White Heather heads up a remarkable squad of volunteers to make the Peel Festival a success. Photo: W M Nixon

Peel is a natural centre to draw in boats from Scotland, Ireland north and south, North Wales, and northwest England, so much so we had to stop ourselves thinking it was like a conference of Sub-Saharan African states, as the gathering was eventually to include Their Excellencies the Presidents or Senior Plenipotentiaries of Nioga, Dboga, Nwoga and Soga. More boats came in on every tide with more than 70 finally in the fleet, and as they wouldn't be able to get out across the gate-flap until late morning next day (Friday August 9th) for the first Parade of Sail, there was ample time in the sunshine to inspect the gathering in its glorious variety.

Stu Spence's 1875-vintage Pilot Cutter Madcap from Strangford Lough was in, recently back the Isles of Scilly where they'd renewed the rudder stock after breaking it west of Brittany, and steering themselves unaided by the cunning use of trailed buckets all the way to Scilly, where with considerable ingenuity they fixed the rudder. The crew for this remarkable feat included noted Isle of Man sailor Joe Pennington whose own restored Manx longliner Master Frank was another of the stars of Peel.

"Dock probes". Bowsprits were everywhere – these are on Mona, Vilma and (foreground) Madcap Photo: W M Nixon

The sterns came in all shapes and sizes – these are (left to right) Madcap, Vilma and Mona Photo: W M Nixon

The Bisquine-rigged Peel Castle from West Cork, and outside her the Warington-Smyth cutter Dreva from North Wales. Photo: W M Nixon

We still await a photo which does justice to the West Cork-based Bisquine-rigged Peel Castle under sail (it would need to be in a lot of wind). Meanwhile, this one of her setting up her spars gives some idea of the eccentric rig which Graham Bailey has installed. Photo: W M Nixon

Ingenuity on a massive scale had also been involved in the creation of Graham Bailey's lugger Peel Castle from West Cork, which despite her name was originally a 50ft Penzance fishing boat built in Cornwall in 1929, but had been so named because Peel Castle was a familiar landmark for the roving Penzance fleet, and it is also the title of a much-loved fishermen's hymn. Though built as a motorized vessel, this fine vessel effectively had a sailing hull, thus when Graham bought her in 1999 he was acquiring a traditional sailing hull just as new as he could get. He spent nine years restoring and converting her at Oldcourt on the Ilen River, rigging her as an eye-catching French bisquine. With three masts in a fan configuration, she certainly looks unusual, but her sailing record speaks for itself, as she has cruised the length of the Mediterranean to Greece, and was in Peel in the latter stages of a three-month round Ireland cruise with extras which had already included a detailed cruise of the Hebrides and a passage out to St Kilda.

The Galway Hooker Naomh Cronan was built in Clondalkin, West Dublin, by a co-operative which still functions successfully after 15 years. Photo: W M Nixon

The Albert Strange yawl Emerald sailed south by Scottish owner Roger Clark was one of many smaller craft taking part in Peel 2013. Photo: Carol Laird

Joe Pennington's Manx longliner Master Frank is the sole survivor of a once numerous Ramsey-based sailing fishing fleet. Photo: W M Nixon

Irish traditional boats were flagshipped by the big Galway Hooker Naomh Cronan, which has been built and kept going for a remarkable 15 years by a co-operative based in Clondalkin in West Dublin, while the long story of Welsh slate schooners was represented by Scott Metcalfe's Vilma from the Menai Straits. She may have started life in 1934 as a ketch-rigged Danish sailing fishing boat, but when Scott and his wife Ruth restored the hull at their boatyard in Port Penrhyn on the Straits, they fitted her with a classic Welsh schooner rig, with the square sails aloft on the foremast mainly handled from deck. The hull certainly shows Vilma's Baltic origins but her rig, as we were to see when the Parade got going, is very much Welsh schooner, and apparently easy to handle, though that may have been the skill of the crew.

Vilma was one of the stars of the show. Photo: Carol Laird

Finally the gate-flap opened later than expected on the Friday morning, and those who were up for the Parade – not everyone by any means – went out onto a lively sea with the sun coming and going and a good breeze sweeping in from the west. Provided we didn't have to go to windward, Ainmara could carry full main, and so long as we kept reaching, she could carry jib tops'l too. So with Brian on the helm, she reached up and down in all her finery, and though we had to throw the outer tack a couple of miles out in a rumbly seaway each time we shaped up to parade back towards Peel, when nearing the shore on the inward track we asked our helmsman to tack as far up the outer harbour as he could at the inner turn in order to provide the smoothest possible water for elderly gentlemen hopping about the deck to clear sheets.

Zapping along – Ainmara at full speed as she shapes her course in towards Peel Castle and the circuit of the Outer Harbour. Photo: W M Nixon

Being a biker, Brian is an ace close quarters helmsman, and each time coming in he brought Ainmara right into the upper reaches of the outer harbour as though he expected to go straight on up the main street. Then a long elegant curving tack, and out we went again with everything setting to perfection before open water was reached, and the old girl outsailing everything else large and small, all great fun.

We'd more of the hospitality that evening with a substantial supper in the Masonic Hall and a great session in the sailing club with Adrian Spence and Joe Pennington in fine form as they detailed their experiences in getting the rudderless Madcap in to Hughtown from somewhere off Ushant, and then a blow-by-blow account of the re-installation of the re-built rudder.

Everybody has a right to their opinion....Joe Pennington, Dickie Gomes and Adrian "Stu" Spence in conference in Peel S & Cr C. Photo: W M Nixon

The Peel people were as good as their word in putting the makings of breakfast on board each morning, but they had started gently enough with standard bacon and egg and the usual extras on the Friday. Then Saturday started the grown-up breakfasts, with a bag of magnificent Manx kippers placed into the cockpit. Our captain became the kipper skipper. We were pleasantly surprised at how much of a dab hand our master and commander was in cooking them lightly to perfection, and by the time we got back from the island, it was difficult to imagine starting the day any other way.

That Saturday (August 10th) was a sort of public interaction day, and included a "dirty boatbuilding" competition beside the harbour, with each team being given enough material to build a small boat – well, not so much a boat, more something that would just about float - then they were given a time limit to finish. The whistle blew to start, it blew again to signal time up, and the winners were the first team whose crewed boat managed to get across the harbour. They had all the teams they needed, though few enough old gaffer owners took part, as they reckoned most of their winters were spent like this, and they'd prefer to do just about anything else, while for Ainmara's crew, it was the day of the great steam train ride.

It may be the Peel Traditional Boat Weekend, but walkies are still expected. Photo: W M Nixon

Back in Peel for the Saturday night festivities, Andy Hall, Commodore of the Peel S & Cr C (which is twinned with Down Cr C) had told us not to eat ourselves silly early on, as the real feasting would take place in his club from 9.0 pm onwards. It was a masterwork of voluntary enthusiasm. His members threw themselves into preparing a mountain of queenies (the succulent Manx queen scallops) cooked six different ways, and a very eclectic clientele (for this seems to be one of the highlights of the Manx social calendar) threw themselves into a massive over-consumption in which all pretences at dining delicacy went by the board. We ate ourselves to a standstill with strangers now the best of friends, but it wasn't an exceedingly late night, for with a week's supply of protein taken aboard in one go, we'd to go back to the boat at a reasonably early hour to sleep it off.

It must have all been cooked to perfection, for there were no ill effects in the morning (Sunday August 11th) and we could breakfast off the skipper's kippers with relish. But while our guts were well settled, the weather was anything but. Though a passage home was a possible if rugged proposition for that Sunday with a fresh to strong sou'wester expected, strong west to nor'wester forecast for the Monday would have meant a dead beat, and no go at all for ancient craft.

We were all three on a three-line whip to be back by Monday night. So instead of taking part in Sunday's Parade of Sail, Ainmara returned across the Irish Sea while we could. Even if it did involve a demanding slug of a passage, it was a shrewd move, for anyone from the east cost of Ireland who stayed until Monday didn't get back until Tuesday.

It was a couple of weeks before news of the awards filtered through. Not surprisingly, both Vilma and Peel Castle received major trophies. But as we'd been a no show in the second Parade of Sail, it was a complete surprise that Ainmara had been awarded the Creek Inn Trophy for Best in Show for her one appearance on the Friday. It was the jib tops'l wot done it. All credit to Mike Sanderson of Sketrick Sails for making the old girl a very elegant set of threads. It was a sweet ending to two seasons of centenary celebration.

"It was the jib tops'l wot done it......" Ainmara in fine form, on her way to winning the Creek Inn Trophy for 'Best in Show'. Photo: Carol Laird

Awards for RNLI Volunteers on Isle of Man

#RNLI - Peel Lifeboat Station is three times proud as a trio of its volunteers will receive awards for their services to the RNLI.

IsleOfMan.com reports that the badge winners were announced at the RNLI headquarters in Poole as part of its 2012 awards list.

Bronze badges will go to Francis Watterson and press officer and past chairman Malcolm Kelly, while Adrienne Teare was awarded a gold badge.

All three will be presented with their badges at a function later this year.

RNLI Peel is one of five lifeboat stations on the Isle of Man servicing much of the Irish Sea between northern England, Scotland and Ireland.