#YACHT DESIGN – If weight, breadth, height and thickness are your primary concerns in evaluating a new book, then this is for you writes WM Nixon. If very high production values, with quality printing, impressive layouts, and the visionary use of a wide range of historic photos are high on your priorities, then this will get your approval. If an inspired text, elucidating many formerly tangled matters of interest in sailing and design history, and all set in a clearly in a comprehensive context which provides a superb socio-economic historical analysis of an important part of Scotland at the height of its maritime, engineering, scientific and industrial glory, then you'll delight in this. But if one of your special pleasures is browsing through a comparative display of properly presented sets of yacht designs, then you'll be disappointed – the few drawings shown in this otherwise magnificent book are little more than sketches used to illustrate changing design trends.

It may well be that the team involved in producing this masterpiece plan to bring out a book of Watson designs in due course – ideally, it might be of broader scope, taking in the designs of all the main Scottish yacht designers. Certainly if the large and varied selection of the more significant designs created by Watson himself, or together with his team as head of a busy drawing office, were included in this volume, then we'd have to think of having neat mini forklift trucks and strong lecterns available for all readers. As it is, it's a bonny baby, chiming in at a smidgin under 3 kilos, or 6lbs 8 ozs if you're in a maternity ward, and it's to the credit of those involved that they've kept it down to this weight, which permits an attractive posting and package service anywhere in the world.

So wherever you are, go for it. This book is right up there with the legendary Royal Cork history in terms of breadth and quality, and in terms of information in many arcane but relevant topics, it's in a league of its own. George Lennox Watson was a multi-talented individual who was the personal expression of Scottish creative and practical genius at its fullest flower. Anyone who thinks only of Glasgow as the place where they invented the deep fried Mars bar will find this work by Martin Black a surprise and a delight, and a cause for admiration of the huge technological and educational advances made by the people of southwest Scotland in the 19th and early 20th Centuries.

Watson died young, aged 53 in 1904. Yet although he was cut off in his prime, such was his contribution to design development at a time of rapid change that, years later, when the great Olin Stephens was asked who he reckoned was the greatest yacht designer of all time, the response was brief: "Watson, of course".

Because it was a magnet for those interested in industry and innovation, Glasgow in its expanding years was one of those places where the emerging Victorian middle classes were soon making their mark. New professions being delineated, and their areas and methods of work codified. Doctors were of course already on the scene, but rapid specialization in medicine saw new disciplines emerging within healthcare. Architects had their functions clarified, as did civil engineers, surveyors and a host of other new professions such as accountancy.

George Lennox Watson, born 1851, came from a well-established medical family, but his own interest was in the design side of the maritime world, and after a brief time as apprentice in the drawing office of a shipbuilding firm, he established his own yacht design office in 1873. He was still a very young man, and far from yacht design being comfortably established as a worthy profession in its own right, until he set up his firm virtually all yacht designers had been employed as in-house developer of design ideas, the employees of boatyards. The idea of a designer setting up his own office and acting as intermediary between owners and several yachtyards was novel – indeed, Watson may have been the first in the world.

It wasn't easy, and as he struggled to establish his firm, and in developing his knowledge of what makes a sailing boat fast, his painstaking and pioneering research was inevitably rather basic. Thus in his early days he tended to be conservative in outlook – he couldn't afford a flop, and he opposed any changes in rating rules which might make his research and his designs obsolete. But the interesting thing is that as the firm of G. L. Watson acquired a sound reputation in the hard-nosed world of Glasgow business, and the toffee-nosed world of big time international yachting, he became more innovative, indeed positively adventurous.

The late 1880s and early 1890s were the times of the most rapid change. The Watson office went from producing narrow-gutted straight-stemmed heavy cutters, briefly through a period of clipper-bowed lovelies, and then very quickly into boats which became personified by the extraordinarily beautiful Britannia, the 121ft cutter design by Watson and built on the Clyde by Henderson for the Prince of Wales, with Willie Jameson of Portmarnock in north Dublin in the honorary but key role of Owner's Representative throughout the building. Jameson was to be the successful amateur sailing master on Brittania for several seasons, and his friendship with Watson flourished until the letter's untimely death a decade later.

Britannia was a first class racer all her life, until George V – who loved the boat with a passion – decreed she should be scuttled on his death, and she was sunk south of the Isle of Wight in 1936. Her near sister Valkyrie II was owned by Lord Dunraven of Adare in County Limerick, whose enormous wealth is credited in this book to his business acumen in buying a hugely successful coal-field in South Wales. I'd been under the impression his acumen lay in marrying a young lady of Wales whose dowry included land which later turned out to be a coalfield, but no matter.

Be that as it may, Valkyrie didn't last as long as Britannia, she was sunk as a result of an epic collision (sadly, one man was killed) while racing in the Clyde in 1894 . But the point is, how is it that Watson's office, having been designing fast but very traditional and ancient-looking racing cutters up until 1890 and later, were suddenly in 1892 proposing these sleek very new-style boats, and seeing them launched in 1893? These wonderful yachts, which still seem modern to us, with their sweet easily driven normal hulls, elegant bows (dismised as "spoons" by conservatives at the time), and virtually separate deep keels. How come?

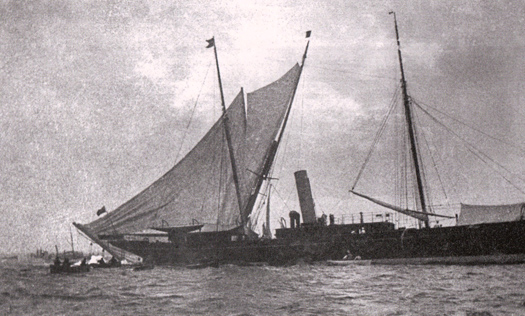

The sinking in the Clyde of Valkyrie II after a collision with Satanita in 1894

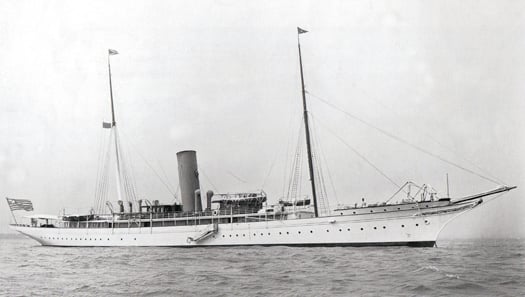

By this time the Watson office was a thriving concern, partly thanks to a huge business within it creating enormous steam yachts for the mega-rich on both sides of the Atlantic. With the need to churn out acres of design to meet many needs, innovative young designers were employed as draftsmen in what was a hotbed of creativity and novelty, and they were thus enabled to provide Watson with some very advanced concepts for his approval and development.

Thus some would argue that the prime mover in the Watson office's relatively sudden and very significant shift to more clearly delineated shallower hulls, and the initially much-derided spoon bows, was primarily a young draftsman employee called Alfred Mylne, who later, of course, established himself as a leading designer in his own right. But in 1892, he was still just an employee - anything that came out of the office had to be signed off by Watson himself.

The 10 Rater Dora of 1891 marked a significant change in the shape of Watson's yachts

Though it may have been the 18-year-old Mylne who saw through the change with the first spoon bows for the new 2.5 Rater Ornsay in 1891, and more importantly, the much larger 10 Rater Dora which, like Ornsay, was additionally innovative in having a centreplate, it is a bit unfair of some partisan sailing folk in Scotland to claim that the sensational Britannia and Valkyrie in 1893 were actually designed by Alfred Mylne. However, this book does make the point that after his own work overload became evident in 1895, Watson entrusted all the design work on smaller yachts to Mylne, whom he regarded as his protégée.

The detail on all this and much more can be followed with interest and pleasure, thanks to the complete nature and thoroughness of this book, which does justice to a remarkable man. Watson was immersed in all aspects of design and business – his mantra was: "Straight is the line of duty, curved is the line of beauty'. It's a different spin on the comment by Gaudi, the eccentric architect of the fantastic Sagrada Familia cathedral in Barcelona, that "straight lines are for mankind, curves are of God".

On the business of yacht design, Watson commented: "The designing of cruising-sailing yachts provides a man with bread, that of racers with bread and butter, and that of steam yachts with bread, butter – and jam". But in addition to his main lines of work, Watson had a mission – creating effective lifeboats for the Royal National Lifeboat Institution, which he did for free. This work started in 1887, and by the time the designer died seventeen years later (of heart failure exacerbated by chronic rheumatoid arthritis) the Watson name was synonymous with the best lifeboats in the world, and he had seen the RNLI through, from rowing boats to rowing/sailing boats and then on to motor-powered lifeboats – a motor-powered prototype was being tested in 1904, the year of his death.

The jam on the bread and butter – in financial terms, the main part of Watson's business at its height was the design of elegant steam yachts for multimillionaires on both sides of the Atlantic. This is the 1266 ton Warrior designed for F W Vanderbilt in 1903

George Lennox Watson was a great and a good man, and this book is as much a worthy tribute to him as a man, as it is to his extraordinary talents as a yacht designer. The maritime community worldwide will be grateful to Hal Sisk, who has brought together the creative team to publish this extraordinary volume, and to Martin Black whose research and dedication have given us an exceptional insight into one of the giants of the already distant world of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries.

The personal mission. From 1887 until his death in 1904, G L Watson worked unpaid as the designer for the RNLI. This is Dunleary, the Kingstown (Dun Laoghaire) No 2 Watson Sailing Lifeboat, built by Hollwey of Dublin in 1898. She was in service until 1914, and saved 24 lives

G L WATSON

The Art and Science of yacht Design.

By Martin Black. 496 pages, fully illustrated, including many previously unpublished photos.

Published by Peggy Bawn Press, c/o Copper Reed Studio,

94 Henry St.,

Limerick

www.peggybawnpress.com

€89 inc p & p worldwide.