It is ironic that the internationally-recognised abbreviated sail number identification on Irish racing boats should be IRL writes W M Nixon. For in global tech-speak, IRL is the acronym of “In Real Life”. If the rather intriguing way of existence we have in Ireland these days truly is Real Life, then all we can say is fasten your seat belts, put on the goggles, and be prepared to believe anything at least once.

Nowadays, our senses are so assaulted by hugely sophisticated electronic data that it can be difficult, if not impossible, to say where reality ends and artificiality begins. And in any case, the signals which the various human sensors are transmitting have to go though so many conduits before they reach the brain and the processing therein, that you could be forgiven for thinking that an extra layer or two in the out-of-body world can’t really make all that much difference.

Now you see it, now you don’t – these competitors in the ICRA Nationals 2019 at the RStGYC in June are actually celebrating their participation In Real Life. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

Now you see it, now you don’t – these competitors in the ICRA Nationals 2019 at the RStGYC in June are actually celebrating their participation In Real Life. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

Thus it could well be that the categorizing of anything as being In Real Life is a shrinking area. If we haven’t seen it on screen or experienced it through other Virtual Reality devices, then we don’t believe it. And what you see on screen can be whatever those who are screening wish it to be.

These meandering thoughts are prompted by the rumour from down Kerry way (where rumour is reality) that the association of the magnificent sea rock monastery of Skellig Michael with the Star Wars movie franchise has been so successful in promoting local tourism that there’s a move afoot to rename the entire and utterly sublime Kerry coast as “Star Wars’ Last Frontier”.

The Star Wars fighter/freighter flies past the Little Skellig on the way to land people and cargo on Skellig MichaelDoubtless, it emanates from Kilgarvan, which isn’t even on the coast, but this hasn’t stopped that mountainy village from producing some of the most off-the-wall ideas in Irish public life. So what are those of us, for whom Skellig Michael and the coast inside it have such special sailing associations, going to think? What are we to make of its possible re-packaging as something which is basically totally imaginary as part of an international entertainment brand?

The Star Wars fighter/freighter flies past the Little Skellig on the way to land people and cargo on Skellig MichaelDoubtless, it emanates from Kilgarvan, which isn’t even on the coast, but this hasn’t stopped that mountainy village from producing some of the most off-the-wall ideas in Irish public life. So what are those of us, for whom Skellig Michael and the coast inside it have such special sailing associations, going to think? What are we to make of its possible re-packaging as something which is basically totally imaginary as part of an international entertainment brand?

For branding is what it’s all about. Those of us who have known and loved Ireland’s Atlantic seaboard, both by sea and land, for decades had distinctly mixed feelings about its re-branding as the Wild Atlantic Way. Certainly it’s a snappy little phrase, but snappy little phrases seem like something in questionable taste in attempting to capture the magnificence of this majestic coastline.

Yet as that great showman P T Barnum so pithily put it, “Nobody ever went broke by under-estimating public taste.” To say that the Wild Atlantic Way has been a marketing success is like saying that the Eiffel Tower is a tall and conspicuous iron structure. It has been pure marketing genius. And inevitably the marketing power of the Wild Atlantic Way has brought the problems of success, such that lovers of the Atlantic coast in unsullied form can only console themselves with the thought that many of the roads are so blessedly small that the inevitable tour buses cannot negotiate them.

Eternally magnificent in their raw state, but the Cliffs of Moher have become so packaged these days as to be almost institutionalised

Eternally magnificent in their raw state, but the Cliffs of Moher have become so packaged these days as to be almost institutionalised

Thus the visiting groups tend to be bussed to the more accessible places in such crowds as to spoil them, so much so that if you were anywhere near the Cliffs of Moher because your will to live is in some doubt, don’t worry about the uncertainty - the scene at the cliffs and its Visitor Centre and bus and car parks will soon make you genuinely suicidal.

Others react to this Wild Atlantic Way thing in a more positive style. A recent posting on the ketch Ilen site by Gary Mac Mahon of the Ilen Project in Limerick shows a photo of Conor O’Brien at the helm of the ketch Kelpie off Ireland’s west coast in 1913, and the Sage of Shannonside describes it as being a time when this was the “Wild Authentic Way”, which is neat.

Conor O’Brien of Foynes Island at the helm of his ketch Kelpie off the West Coast of Ireland in 1913 when it was still the “Wild Authentic Way” Photo courtesy Gary Mac Mahon

Conor O’Brien of Foynes Island at the helm of his ketch Kelpie off the West Coast of Ireland in 1913 when it was still the “Wild Authentic Way” Photo courtesy Gary Mac Mahon

Yet the re-branders persist in going about their work for all Ireland, and for some time they’ve been trying to get us to think of a particular area as The Ancient East, which immediately projects an image of a ruinous and overgrown region inhabited almost entirely by dribbling geriatrics. This may indeed be how the rest of Ireland likes to see us, but if the marketing wonks simply called it Leinster and encouraged the rugby team to keep winning, it would surely do much more good.

The biggest problem in terms of a snappy marketing phrase continues to be the Midlands. Those of us of a boat-minded persuasion are more than happy to think of it as the Shannon and its lakes, but maybe the difficulty is that the international perception of the word “Shannon” is of an airport where old-style Russian leaders used to sleep off an excess of drink, a place where there are secretive comings and goings of enormous and minimally-marked aircraft under cover of darkness. Definitely not an image one wishes to associate with a cherished holiday area.

Be that as it may, although Kerry is one of the biggest jewels in the crown which is the Wild Atlantic Way, being the Kingdom of Kerry (which is how it sees itself despite being up to the eyeballs with republicanism), it wants to reassert its own identity, and it seems that Star Wars Last Frontier is a front runner in the re-naming stakes.

It’s just grand, but where’s the reality of the Kerry coast in all this?

Not to worry. They can call it whatever they like, but it’s still the real deal under any name for those of us who have been sailing it for longer than we care to remember.

The first time was very well back in the previous Millennium when we slugged our way southward from Inishbofin off the Galway coast in the ancient yawl Ainmara, and after a night or two at sea found ourselves in Brandon Bay in Kerry, anchored off the hospitably little settlement of Brandon itself. It was a place well furnished for hospitality with three pubs, in one of which we had an enormous feed while swilling pints and watching the new television channel with Dev himself making a very prescient broadcast about the perils of this mysterious medium.

First impressions of Kerry. Ainmara in Brandon Bay a long time ago, having sailed mostly to windward, and at one stage through a summer gale, from Inishbofin off West Connemara. Photo: W M Nixon

First impressions of Kerry. Ainmara in Brandon Bay a long time ago, having sailed mostly to windward, and at one stage through a summer gale, from Inishbofin off West Connemara. Photo: W M Nixon

Whether you come along the coast from north or south, Kerry makes an indelible impression, and coming from the south the effect is heightened if you make your entrance through Dursey Sound under the creaking cable car. Emerging on the north side of the Sound, the entire glorious panorama of the Kerry coast is spread out across the horizon, from the Bull Island, the Blasket and the Skelligs to the west, right round to the rising purple heights of McGillycuddy’s Reeks (it’s easier to say it as “Mackle-cuddy” even if that’s not entirely correct) as they soar towards the peaks about Carrantuohill to the east.

Under these many hills and mountains are enough inlets and anchorages and harbours and inshore islands to interest you for a week or a fortnight, the magic of it summed up in names like Ventry, Dingle, Cromane, Kells Bay, Knightstown, Cahirsiveen, Ballinskelligs, Derrynane, Sneem, Parknasilla, Dunkerrin, Kilmakilloge, and Ardgroom with many others.

Portmagee on the mainland side of the south end of Valentia Sound is now seen as Port Star Wars

Portmagee on the mainland side of the south end of Valentia Sound is now seen as Port Star Wars

And there in the midst of them is Portmagee, which has reinvented itself as Port Star Wars, providing the quickest access to Skellig Michael. It’s the reality of modern life that the place is thriving because of its association with a contemporary sci-fi film series. And those who would be inclined to sniff at such a thing would do well to remember that they may be of a generation which first became most vividly aware of the special magic of Skellig Michael because it featured in Kenneth Clark’s classic 1969 TV series Civilisation, its extraordinary history as a remote island mini-monastery being featured, for its isolation meant it survived as an outpost of civilization while the rest of Europe was plunged for a century into the horrors of the Dark Ages.

One of the most special moments in Irish offshore racing. Liam Shanahan helming the 2015 Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race winner Ruth with the Great Skellig put astern.

One of the most special moments in Irish offshore racing. Liam Shanahan helming the 2015 Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race winner Ruth with the Great Skellig put astern.

For most of today’s sailors, Skellig Michael rears its handsome head every second year as the final turning point in the Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race. In fact, the turning point is a waypoint to the west of the Skellig which is supposed to keep contestants safely clear of the Washerwoman Rock to the southwest of the Skellig, whose breakers are clearly visible in our header photo.

But in the 2017 race when the fleet were beating from the Fastnet to this turn, one boat which had better remain anonymous was doing very well by energetically tacking along the mainland shore, and they only came out to the Skellig waypoint turn at the last possible minute, which meant the tracker showed that they sailed through the gap between the Skellig and the Washerwoman, yet still complied with the requirement to leave the waypoint to starboard. You know who you are……..

Racing round the Skellig is better than not seeing it at all. But a leisurely visit ashore was best of all if, during a cruise in the area, the weather happened to be exceptionally settled and the ocean relatively swell-free. We’re talking of times past before the development of the current regulated visiting system, though doubtless a cruising man or woman with the golden tongue could talk their way ashore as being successors to the Irish voyaging monks of the early Middle Ages, a line we successfully took when getting onto the very attractive monastery island of Caldy off southwest Wales many years ago.

Map of Skellig Michael. The most sheltered landing place is at Blind Man’s Cove at the northern end.

Map of Skellig Michael. The most sheltered landing place is at Blind Man’s Cove at the northern end.

Our visit to Skellig Michael was back in 1982, when things were very relaxed. The first Star Wars film had only been made eight years earlier, and any idea of associating the natural drama of Skellig Michael with the series was still many years in the future, so we were able to enjoy Skellig Michael in its last years of innocence with a certain air of unreality.

In fact, there was something unreal about that entire cruise, which was round Ireland anti-clockwise in the Hustler 30 Turtle in conditions so summery that we had our first transit of the Joyce Sound Pass inside Slyne Head, coming from the westward as though going through the Grand Canal in the midst of Kildare. Later we spent some leisurely time on the Great Blasket Island before overnighting in Knightstown on Valentia, then waking there early in the morning to an even more perfect day with a gently fading easterly, which allowed us to run under spinnaker out to the Skellig.

There, the wind obligingly fell away to enable an easy landing of two of the crew while the third reversed Turtle away from the island quay to await his turn to land later. But nearby, our friend Larry Swan from Galway with just his son aboard Finola was so determined that they should go ashore together that they anchored right under the cliff in 25 fathoms and made the joint visit which they thought well worthwhile, even if it did take them an hour and ten minutes to retrieve their ground tackle afterwards.

Subsequently, we learned that another cruising boats with whom we’d been socialising with some energy in Knightstown had taken so long to emerge into the new day that it was well into the evening by the time they got to the Skelligs. The day’s ferry schedule was long completed, there were no other cruising boats seeking to land, and they’d the luxury of having the landing place in Blind Man’s Cove to themselves for a quiet visit as the sun set.

The height of luxury – on a very rare calm evening, you can have the Skelligs landing at Blind Man’s Cove to yourself, or at least you could before Star Wars came along.

The height of luxury – on a very rare calm evening, you can have the Skelligs landing at Blind Man’s Cove to yourself, or at least you could before Star Wars came along.

While we were there, at the landing place and around the steep sea mountain itself there was something of a regatta atmosphere - not over-crowded with those who had come over from Portmagee via the launch service, yet with enough people for interesting variety, ranging from those who were clearly on a personal pilgrimage, to a group of athletic and sun-tanned young German women who were out-doing each other in the skimpy bikini stakes. Skellig Michael at that time could absorb it all, and it really is one of those places which exceed all expectation when you finally get there.

A totally other-worldly place – the beehive stone huts of the miniature monastery on Skellig Michael high above the Atlantic.

A totally other-worldly place – the beehive stone huts of the miniature monastery on Skellig Michael high above the Atlantic.

Unfortunately these days too many people want to do that, so we cherish our memories of Skellig Michael, and while two of us found even the little monastery with its distinctive stone beehive huts almost too vertiginous, our third shipmate was immune to heights, and he crossed Christ’s Saddle to the hermitage on the highest point.

There he found the legendary Mr Murphy the stonemason and conservationist from Valentia, who spent each summer on the island on maintenance projects and went about his work at dizzying heights with quiet unconcern so that sometimes he seemed to hover like a hummingbird with such effortless ease with no visible support that our shipmate, in returning across the Saddle, was so inspired by what he’d seen Mr Murphy do that he almost fell off. But he’d the thoughtfulness not to tell us this for a day or two.

For contrast, we headed on to the anchorage of Derrynane and the abiding presence of Daniel O’Connell and Conor O’Brien and Lord Dunraven and all those other Derrynane summer people of times past, and finally after a last Kerry anchorage in the hidden natural harbour of Cleanderry (the entrance is only 25ft wide), we bade farewell to what may well become the Star Wars Coast and sailed south to windward through Dursey Sound with some very short tacks, and headed on to the delights of West Cork.

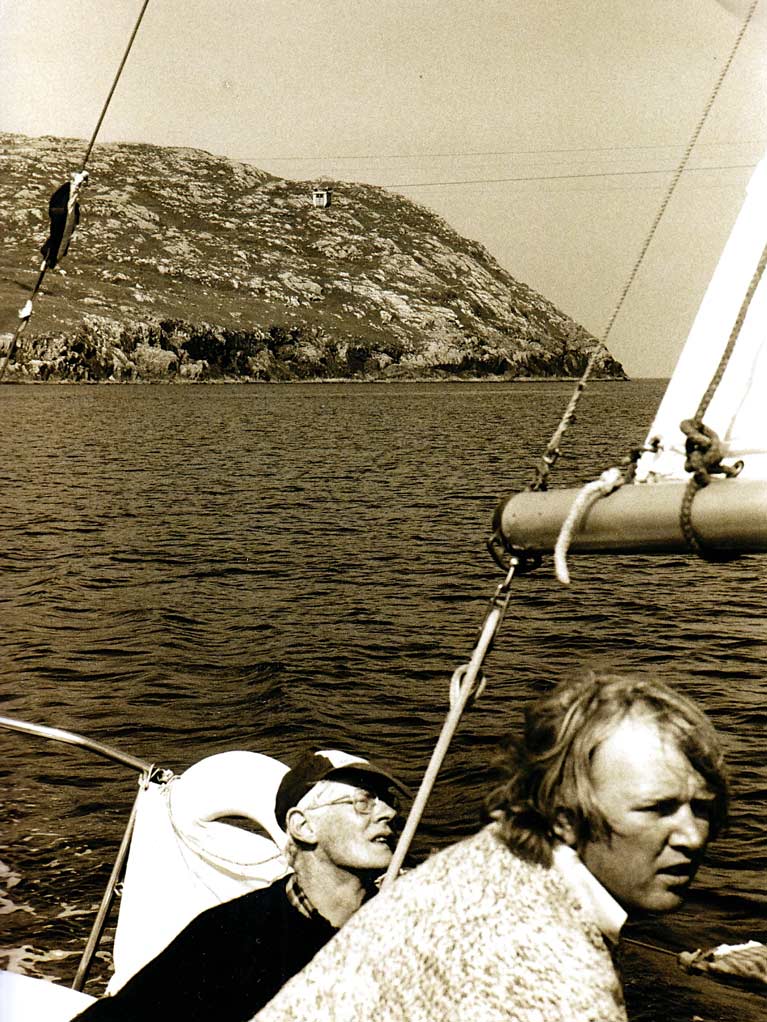

Departure from the Kerry coast – tacking southward through Dursey Sound on Turtle, with the cable car creaking its way across overhead, while the late Brendan Cassidy concentrates on getting the best windward performance, and Johnny Malcolm wonders if we aren’t getting a bit too near the mainland coast of Beara. Photo: W M Nixon

Departure from the Kerry coast – tacking southward through Dursey Sound on Turtle, with the cable car creaking its way across overhead, while the late Brendan Cassidy concentrates on getting the best windward performance, and Johnny Malcolm wonders if we aren’t getting a bit too near the mainland coast of Beara. Photo: W M Nixon

So would a re-branding of the Kerry seaboard as the Star Wars Coast, and thus something extra-special within the Wild Atlantic Way marketing project, be beneficial in the long run? The jury is surely out on that. But you can sympathise with the people of Kerry in trying to use names from elsewhere for their benefit. After all, does Kerry benefit in any special way from the quintessential Irish product being called Kerrygold? And apparently, it has been ruled in some court or other that “Kerry” is such a generic name that people are free to use it for products regardless of where they are produced in Ireland, or indeed anywhere in the world for all we know.

But the “Star Wars’ Coast”? Would that work IRL – In Real Life? Perhaps. But not as we know it, Jim….