A woman. A man. Three days and two nights together at sea. Racing in a cramped 30ft boat. Under 24-hour surveillance. It sounds like the latest pitch for a Reality TV show. Arguably, it is. But it’s also the new Olympic sailing challenge writes W M Nixon.

However, the real speculation has only just begun about the eventual planned re-introduction of keelboats to the Olympic sailing lineup in 2024. Behind the social media noise, it’s mainly about bringing proper offshore racing to the five-ring circus. But as soon as it was revealed that the changes would involve bringing in a keelboat and dumping the veteran Olympic Finn, the general fixation seemed to be about the boats rather than the people and the sport and the audience impact.

There has been all the understandable grief inspired by the demise of the single-handed Finn’s Olympic role. Many see her as the ultimate single-hander, best expressed through Olympic status. And as well there has been the throwback from Star keelboat adherents, who still dream of their quaint machines being re-aligned back into the Olympic gallery.

“Quaint machines”. What is it about the ancient yet ever up-dated International Star? As soon as it was revealed that a keelboat would re-appear in the 2024 Olympics boat lineup, there was a clamour of support to bring back the Star

“Quaint machines”. What is it about the ancient yet ever up-dated International Star? As soon as it was revealed that a keelboat would re-appear in the 2024 Olympics boat lineup, there was a clamour of support to bring back the Star

Inevitably, social media seems to have been immediately swamped by people trying to shoot from the hip with instant opinions. Yet they’ve often managed to shoot themselves in the foot instead of hitting any meaningful target.

But despite this tsunami of snap opinions, we should be a bit more patient, and try to get to the real story. Instead of seeing it as a curious attempt to introduce a less athletic type of boat back into the sailing Olympiad, we should realise that it is all part of sailing’s continuing struggle to maintain its position as an Olympic sport in the first place.

Now admittedly with sailing firmly in place for 2020 at Tokyo, and with the 2024 Olympiad in Paris and the sailing events at Marseilles in sailing-mad France, the position is secure for the next two Olympiads. But beyond that…..?

It all comes down to global viewing numbers. If the public worldwide aren’t buying arena tickets or tuning into the images of a particular Olympic sport, then the International Olympic Committee will begin to query whether or not that sport should be in the Olympic Games in the first place.

Other underlying themes include whether or not the sport in question is truly global in its reach, effortlessly transcending national, racial and economic boundaries. But ultimately the key point is the level of human interest and spectator involvement that the sport engenders.

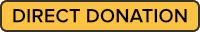

Sailing as a stadium sport in a staged naval battle for entertainment purposes in the Colosseum in Rome. Unfortunately for modern purposes, such encounters involved unacceptable levels of fatality….

Sailing as a stadium sport in a staged naval battle for entertainment purposes in the Colosseum in Rome. Unfortunately for modern purposes, such encounters involved unacceptable levels of fatality….

Thankfully, we no longer have to rely on sailing reinventing itself as some sort of traditional-style stadium sport. Stadiums develop around athletic contests and team games in a natural organic progression which stems from the immediate human interaction between physically present sportsmen and nearby spectators. But any attempts to make sailing an arena event other than by the electronic means of a virtual stadium seem doomed to failure, for the water and the boats keep getting in the way, and sailing does not lend itself to circuit courses.

That’s how it is for the spectating and viewing public. But as sailors, we start from the opposite end of the spectrum – the boats. We always liked to think the Finn singlehander was the ultimate Olympic sailing experience. There was no doubting this very special boat’s unrivalled athletic demands. And she comes with the kind of special pedigree beloved of boat-nuts.

The story of the Finn is a perfect nugget of sailing history. After World War II, the UK hosted the first post-war Olympics in 1948 in London, with the sailing at Torquay. With the massive disruption of the war, the previous Olympics had been all of 12 years earlier, in 1936 in Berlin, with the sailing at Kiel on the Baltic.

The O-Jolle was specially designed to be the single-hander for the 1936 Olympics in Germany. There are still about 500 of them sailing in the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Italy and Switzerland, and they feature in the Vintage Olympic Classes Yachting Games

The O-Jolle was specially designed to be the single-hander for the 1936 Olympics in Germany. There are still about 500 of them sailing in the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Italy and Switzerland, and they feature in the Vintage Olympic Classes Yachting Games

Only four classes had taken part in Kiel, three of them keelboats including the eternal Star. But the singlehander (and only dinghy) was a German design, the una-rigged O-Jolle specially created for the 1936 Olympics, with the Gold Medallist being the Dutch sailor Daan Kagchelland.

A dozen years later, with the world still only partially emerged from the devastation of global conflict, the British hosts accepted that the boat lineup should reflect post-war austerity, but were understandably reluctant to include their recent enemy Germany’s useful O-Jolle. And in face of a demand for an additional two-handed class which was less complex than the Star, they rejected some attractive existing Continental dinghy designs and the International 14 (possibly because it was a restricted class rather than a One-Design), and plumped instead for a slim and attractive new 26ft keelboat, the Swallow.

The other boats reflected established and new trends, as they retained the 36ft International 6 Metre with her crew of five and the International Star with her crew of two, but added the increasingly-popular three-man International Dragon. So keelboats were still very much in the ascendant, as the only dinghy was the new single-hander.

The first Firefly. An excellent two-hander, she was less than ideal as the single-hander at the 1948 Olympics at Torbay

The first Firefly. An excellent two-hander, she was less than ideal as the single-hander at the 1948 Olympics at Torbay

At first glance, they made a weird choice, as it was the 12ft sloop-rigged Firefly. This Uffa Fox-designed planing dinghy (first sailed in 1938) was now being mass-produced in a hot moulding process (“baked like a waffle” they used to say) at Fairey Marine, thereby taking up production potential from the former wartime levels at Fairey Aviation. It was a patriotically popular choice in the heartlands of the British marine industry, but as a single-hander, it would have been very few people’s first selection.

Nevertheless, Denmark’s most dedicated dinghy single-hander, a somewhat introverted young man called Paul Elvstrom, won the Gold Medal in the Firefly. And then he went on to win the single-handed Gold Medal in the next three Olympics, but they were to be sailed in a boat which came to epitomize the Olympic sailing ideal.

The 1952 Olympics were scheduled for Helsinki in Finland, and the Finnish organisers and the International Olympic Committee must have gone to work on the challenge of selecting a more appropriate single-hander even as the sailing at Torquay was underway. For by 1949 a Swedish canoe designer called Rickard Saarby had created a 4.5 m (14ft 9ins) powerful yet classic one-sailor hull with a una rig. It came to be called the Finn in honour of the hosts. And when it ceases to be an Olympic Class after the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, this admittedly challenging yet much-loved boat will have been the longest-serving Olympic dinghy, having performed at 18 Olympics on the trot.

The Olympic Finn in classic action. For sailors, they were the ultimate Olympic ideal. But for ordinary spectators, for all that you can see of the helmsman’s individuality, they might as well be sailed by robots

The Olympic Finn in classic action. For sailors, they were the ultimate Olympic ideal. But for ordinary spectators, for all that you can see of the helmsman’s individuality, they might as well be sailed by robots

That’s not quite as sensational as it sounds, as the other four classes at Helsinki in 1952 were still keelboats – the inevitable Star, the Dragon, the new International 5.5 Metre, and the International 6 Metre. For modern sailors, and the previous generation too, come to that, this must seem like the lineup for the Jurassic Sailing Olympics. Yet such it was, and it didn’t look so different in 1956 in Melbourne, Australia, when they dropped the big International 6 Metre, and introduced the first two-man dinghy.

But although there were now recognizably modern boats on the international scene, the powers-that-be selected a primitive hard-chine machine called the International 12 Square Metre Sharpie. Originally designed in Germany in 1931, she set a gaff/gunter rig and was usefully popular in certain countries which at the time had considerable influence in the decisions of Olympic sailing.

One of the crazier Olympic choices – the International 12 Square Metre Sharpie was the first two-man “dinghy” in the Olympics. It was used just once – in 1956

One of the crazier Olympic choices – the International 12 Square Metre Sharpie was the first two-man “dinghy” in the Olympics. It was used just once – in 1956

It wasn’t until the 1960 Olympics in Rome, with the sailing at Naples, that a modern two-man dinghy made the Olympic lineup. This was the Flying Dutchman, which admittedly was nearly 20ft long, but she was so good she could plane going upwind, and at Naples in 1960 she saw Ireland’s first-ever first place in an Olympic race for Peter Gray and Johnny Hooper of Dun Laoghaire. And then in 1980, she brought Ireland’s first medal, a Silver at the Games in Russia for David Wilkins of Malahide and Jamie Wilkinson of Howth. So there was some sadness in Ireland when the FD’s Olympic career came to an end after the 1992 Games.

The Flying Dutchman, a two-handed dinghy for real Olympians

The Flying Dutchman, a two-handed dinghy for real Olympians

This meandering tale of which boats are in or out in the Olympic scramble can be of enormous – indeed, obsessive - interest to sailing folk. But such things are scarcely comprehended by other athletes, who see sailing as primarily a vehicle activity, arguably not a sport really at all, in which the actual vehicle and its colourful history is of little or no interest.

As to what is required to obtain sport in such vehicles, other athletes can become very bewildered, as sailing is a “sport” in which the participants seem to spend much of their time sitting down, albeit in the most uncomfortable possible way. On top of that, they’re often sitting in such a way that you can’t easily see their faces, and it’s the registering and relating to extreme facial expressions which give other athletes - and more importantly the spectators - a proper sense of connection. For although sailors just love the image of a well-trimmed Finn thrashing to windward, most of the time you can only see the back of the helmsman’s head, and as far as spectator human interest is concerned, the Finn might as well be sailed by a robot.

Thus the developing Sailing Olympics seek to emphasise human interest and personal interaction. That, and witnessing extreme physical achievements. As in: Really Extreme Physical Achievements. Consequently, in the sailing community at large, not only have the instant commentators missed the real point of the reintroduction of keelboats, they’ve also missed the fact that the latest decision of World Sailing’s Equipment Committee at the WS Annual Conference in Florida (with a large and busy Irish contingent) has made sure that at the Paris Olympics, the range of sailing machines and boats will go from one extreme of displacement to another.

The extremes of sailing begin with the almost-no-displacement “vehicle” in the Mixed Kiteboarding Event, with a foiling board fitted with RAM-air (foiling kite) certainly providing extreme physical achievement – arguably to stunt level.

Minimal displacement…..foiling kite-surfing rates high on the sailing sports spectacular rankings

Minimal displacement…..foiling kite-surfing rates high on the sailing sports spectacular rankings

Then in between, there’ll be a still-to-be-decided Mixed Two Person Dinghy of non-foiling displacement form with main, jib and spinnaker – Paddy Boyd, one of many delegates from Ireland at the Florida conference, reckons it will keep the 470 in the lineup, for all that the design has been around since 1963.

But then we’re into totally new territory – the inclusion of a Mixed Two Person Offshore Keelboat. If this seems to be a return of keelboats to Olympic Sailing, perish the thought. For with this particular class it’s definitely not Olympic Sailing as we know it. It’s arguably a new event altogether, as the backbone of this keelboat debut will be an offshore race which will be shaped to fit the prevailing conditions such that it will last three days and two nights, making it far and away the longest continuous event in the Olympic Games.

Heaven help the race Officers at Marseilles in 2024 trying to predict Mediterranean weather with sufficient accuracy to ensure a race of just this length in time but no longer. Yet Cathy MacAleavey – who’s on the Equipment Committee which set the parameters of the new boat – says that is the aspiration.

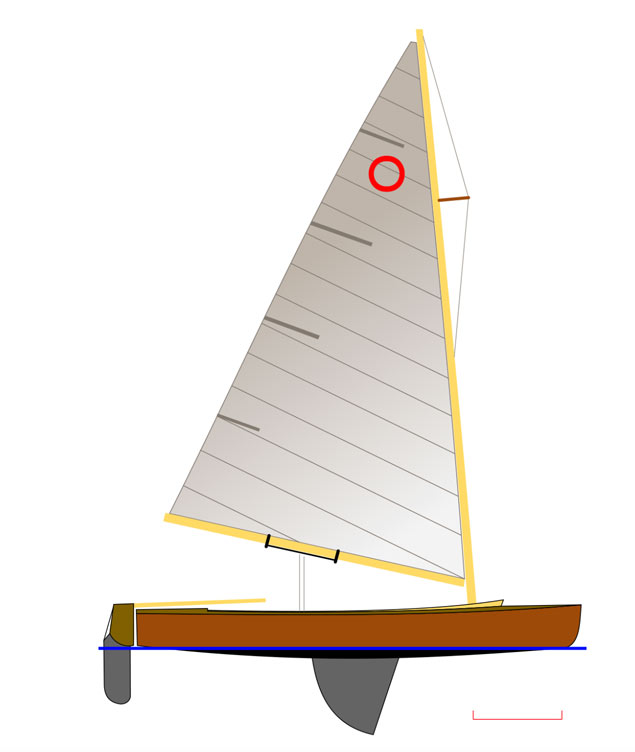

As to the boat which will be used, the length overall will be between 6 metres and 10 metres, definitely non-foiling, and currently talked of as sloop rig with spinnaker, but Cathy reckons they’ll have settled on a genniker by the time the details are being finalized.

Needless to say, the human interest aspect immediately focuses on the fact that it will be a man and a woman together for 60 hours in the confines of a boat which could be as commodious as a Figaro 2, but equally it could be as cramped as a Minitransat 6.5.

Tom Dolan with his Ministransat 650. With a proposed size range between 6 and 10 metres, the possibility of this small size of boat in the Olympic offshore race has to be considered

Tom Dolan with his Ministransat 650. With a proposed size range between 6 and 10 metres, the possibility of this small size of boat in the Olympic offshore race has to be considered

There’ll be miniature cameras everywhere on board, and continuous transmission from all boats while the race is in progress. It may seem intrusive, but that’s the way the Internet is now. The inter-personal chemistry and immediate visual access to interaction with other boats will be everything, and Internet popularity will play a key role in keeping Olympic sailing on the road.

Far from lacking immediate human interest, it will probably have more human interest than most of us can cope with, and running the central communications centre to achieve a cohesive stream will be perhaps the most intensive skills test of all.

It’s certainly an idea whose time has come. Cathy MacAleavey is bubbling over with enthusiasm about it all, and reckons that brother-and-sister or husband-and-wife crews might have an inbuilt advantage – she cites the way that former 49er Gold and Silver Olympics Medallist Nathan Outteridge has teamed up with his sister to race a Nacra 17 towards the Tokyo Olympics, and finds it a fascinating new experience as he moves into his mid-30s.

Cathy MacAleavey and husband Con Murphy. Photo: W M Nixon

Cathy MacAleavey and husband Con Murphy. Photo: W M Nixon

We suggested to Cathy that, what with Francois Joyon winning the Route de Rhum the other day at the age of 62, and the incredible Jean-Luc van den Heede leading the Golden Globe at the age of 73 despite rigging problems that would have stopped most people half his age, then maybe she and Con would be game to have a go 36 years after she last was an Olympic sailor, and 31 years after they together established a very long-standing Round Ireland record. The idea certainly wasn’t ruled out of order. That said, maturity isn’t essential for stamina, as 20-year-old Erwan le Draoulec proved when he won the Ministransat a year ago in some style.

Over in France meanwhile, Marcus Hutchinson has been watching it all from the standpoint of someone who is right at the heart of the Figaro Solo circuit (in addition to his involvement with IMOCA 60s), and he reckons that whatever the ultimate plan, at present the only real training and testing programmes available globally are with the Figaro setup, which has already been well used by several Irish sailors, most recently with a potential Mixed Crew in Joan Mulloy and Tom Dolan.

Joan Mulloy of Mayo and Tom Dolan of Meath raced against each other in the 2018 Figaro series. Photo Alex Blackwell

Joan Mulloy of Mayo and Tom Dolan of Meath raced against each other in the 2018 Figaro series. Photo Alex Blackwell

Being France, the 2024 Olympics will have an emphatic Gallic emphasis which has already been in evidence. Back in the Spring of 2018, there had been a scheme hatched up between some sections of World Sailing and the French sailing authorities to trial five different boats – some of them new – to fit this new Olympic event. Although various factors conspired to prevent it happening, the groundwork has been done, and the intention has been fairly clearcut, so it will probably happen soon enough.

Currently, the underlying plan is that the host nation should provide the boats. Thus one line of thinking is that existing classes such as the appropriate craft in the J/Boat range, the Figaro 2, or the Sunfast 3200 and several others could be used as one-designs for training and selection trials in the nations where they are found in significant numbers, and then in 2024 the national winning crews will turn up in Marseilles and this limited edition of brand new boats will be there, ready to go and equally unfamiliar to everyone.

But 2024 is so very far away. Now that the idea of an offshore keelboat has passed through the preliminary stages, the idea of Olympic offshore racing as a sort of reality TV show is going to gain traction, and Paddy Boyd (who is on the World Sailing Oceanic & Offshore Committee) revealed that while the idea that there should be a trial offshore event in tandem with the 2020 Olympics to test the format seemed to have died the death, at the Conference in Sarasota the whisper was that it may yet re-emerge.

Sarasota, Florida - location for the 2018 World Sailing Conference

Sarasota, Florida - location for the 2018 World Sailing Conference

There’ll be much to-ing and fro-ing before the final decision on boat type for 2024 is made in November 2019’s World Sailing Annual Conference, and by that time it seems quite possible that it will have been agreed that something like a class of Figaro 2s will racing a tandem offshore event at Enoshima on a trial basis.

If it happens, as it looks as though the boats will inevitably be laden down with communications gear, maybe the standard equipment on these proper little offshore racers could also include an air conditioning unit. For the word from Tokyo in July and August 2018 is that that the local climate is so hotly humid as to verge on the putrid. The option of an effective on-board air conditioner could make the trial offshore event the only show in town…….

The 2020 Olympic sailing venue at Enoshima near Tokyo. In summer, the intense humidity can be a problem

The 2020 Olympic sailing venue at Enoshima near Tokyo. In summer, the intense humidity can be a problem