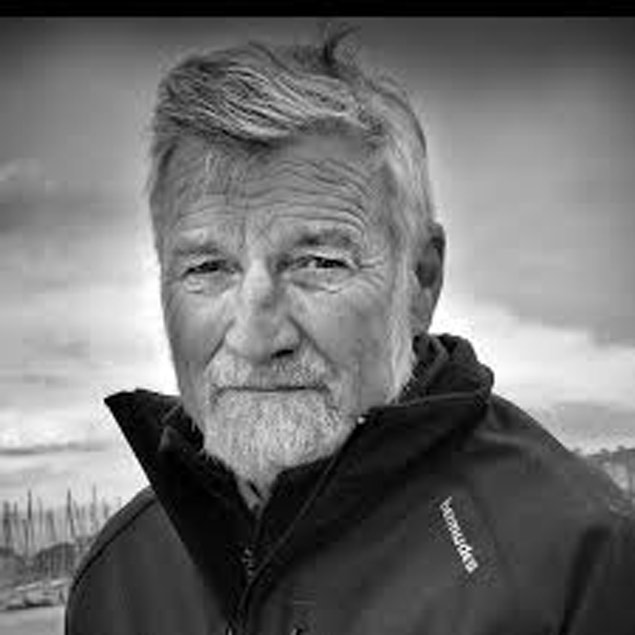

Gregor McGuckin is currently and very deservedly the best-known Irish sailor in the world writes W M Nixon. The sheer gallantry and utter rightness of his efforts to bring aid last weekend to injured fellow Golden Globe competitor Abilash Tomy of India – despite his own boat being dismasted – amounted to selfless heroics of the highest order.

In a weekend in which confused messages were emerging from the incidents in one of the remotest parts of the Great Southern Ocean to the south of the Indian Ocean, the golden thread of the storyline of Gregor McGuckin’s battle to get to Tomy with his jury-rigged 36ft Hanley Energy Endurance gradually emerged as a constant theme.

In the end, as larger organisations were getting to grips with the special problems of a distant rescue, it was France’s workaday fisheries patrol vessel Osiris which emerged relatively unheralded on the scene, successfully carrying out the rescue of Tomy from his mastless ketch Thuriya, and the controlled evacuation of the Irish skipper from his disabled boat in this especially hostile area of ocean more than 1800 miles from Australia.

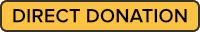

The incidents occurred at the centre of this map. Although there were small islands in the area, the nearest ports were 1800 miles away.

The incidents occurred at the centre of this map. Although there were small islands in the area, the nearest ports were 1800 miles away.

The rugged, harsh and sometimes secretive world of the global operation of fisheries is very different from the adventure-oriented ethos of the Golden Globe Race, and the high-profile formally-structured approach of top officialdom in undertaking such an operation, notably by the Royal Australian Navy and the Indian Navy - Abilash Tomy is an Indian Naval Commander.

For the crew of Osiris – who must have one of the toughest yet most unglamorous jobs in the world – it was all in a day’s work. But for a waiting world which had been fed on stories of how an aerial rescue might be undertaken and how long it would take an Australian naval vessel to reach the scene, it seemed little short of a miracle, and it was only on Sunday morning on Afloat.ie that we were able to confirm that a French fisheries patrol vessel had become the best hope of a timely rescue for Tomy, whose serious back injury meant he had been unable to access fresh water since his 360 degree rolling and dismasting on Friday.

The unglamorous heroine of the tale – the French Fisheries Patrol vessel Osiris. She herself is a ship with quite a history - it may have included piracy. And she was confiscated as an illegally fishing African vessel in French territory, with the new owners making the practical decision to use her for their own fisheries patrols in a decidedly rugged part of the ocean.

The unglamorous heroine of the tale – the French Fisheries Patrol vessel Osiris. She herself is a ship with quite a history - it may have included piracy. And she was confiscated as an illegally fishing African vessel in French territory, with the new owners making the practical decision to use her for their own fisheries patrols in a decidedly rugged part of the ocean.

By Saturday, Greg McGuckin had cleared away most of the wreckage of his main rig and had somehow - despite sea conditions which were still appalling although the wind had eased – erected the jury rig and begun the painfully slow 90 miles to Tomy’s boat Thuriya with some help from his auxiliary engine. But this was not running at full power, as the fuel has become contaminated with sea water which had entered through the fuel tank breathers during the total capsize.

This meant that McGregor was acutely aware that his access to effective engine use might be just for a very limited period. After that, any further progress would be by jury rig only. Thus when the situation was transformed by the arrival of Osiris after McGregor had been hand-steering his slow-moving boat for nearly four days as all auto-steering was disabled, he personally was facing the stark choice of taking the opportunity of a controlled evacuation from his own vessel when it was still available, or hanging on and risking the need of another rescue operation when his struggling boat was further damaged in the next big storm.

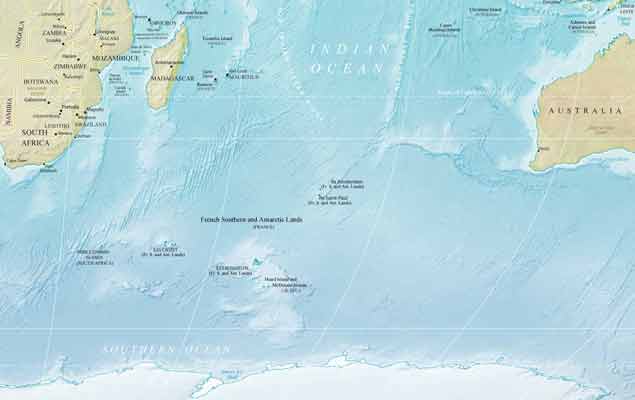

Gregor McGuckin at the start of the Golden Globe, Sunday 1st July with the 1970s Biscay 36 production cruiser Hanley Energy Endurance transformed into a serious ocean-going proposition

Gregor McGuckin at the start of the Golden Globe, Sunday 1st July with the 1970s Biscay 36 production cruiser Hanley Energy Endurance transformed into a serious ocean-going proposition

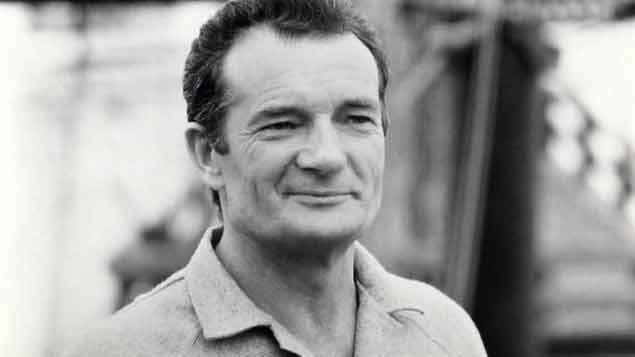

Gregor’s boat as she’d become on September 22nd, battered but unbowed, reduced to jury rig but making progress.

Gregor’s boat as she’d become on September 22nd, battered but unbowed, reduced to jury rig but making progress.

It took great feats of seamanship, courage and endurance to clear the boat’s original broken rig and erect this emergency rig in its place

It took great feats of seamanship, courage and endurance to clear the boat’s original broken rig and erect this emergency rig in its place

The decision he took to request a controlled evacuation was absolutely the right one, though inevitably a painful one too. But the fact that he’d had to do something as quietly heroic as sailing his crippled boat towards Tomy to achieve the supportive recognition he has received is a reminder, were it needed, of how any aspiring international offshore sailor in Ireland seems to have to make at least twice the effort of anyone from any other country in order to get a foothold on the steps of the big-time pathway.

There’s no denying we’re an island with immediate access to offshore racing waters of the most demanding international quality. But ultimately, promoting professional offshore racing is all about population density and national wealth, and the kind of marketing which is always seeking new outlets to remind people of existing products and services, or to introduce new ones.

In Ireland, we’ve a small population and few big companies. And maybe because we have an excess of sea, people tend to look to the land for their sport.

But in France, with its enormous land area, large population in a corporate society, highly-organised social infrastructure, great underlying wealth, and relatively limited direct acquaintance with the sea which thereby makes it an altogether more exotic element, the professional offshore racing setup is much more highly developed. This is shown by the upcoming entry for the Transatlantic Route de Rhum to Guadeloupe in the Caribbean, which starts at St Malo on November 4th – 127 boats are confirmed, all of them receiving international attention, and not an Irish one among them despite it being a known indicator for the Big One, the Vendee Globe in 2020.

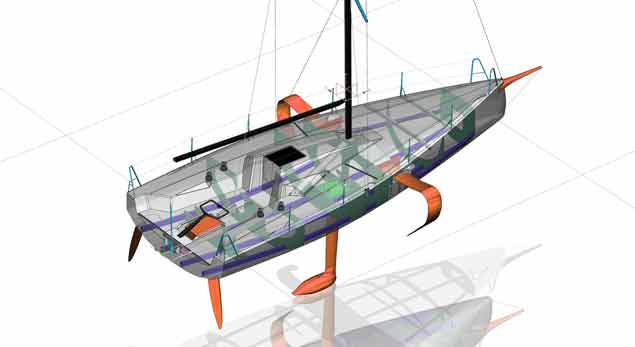

The ultimate challenge. The IMOCA 60 class starting the non-stop round the world Vendee Globe race from Les Sables d’Olonne

The ultimate challenge. The IMOCA 60 class starting the non-stop round the world Vendee Globe race from Les Sables d’Olonne

Yet the development of this quietly confident French sailing pre-eminence, which has been operating for years at many levels with, for instance, French boats winning overall in the last three Rolex Fastnet Races, has been no happy accident. Arguably, it stems from the Glenans Sailing Schools, which began in Brittany in 1947 as a deliberate move to encourage France’s young people into sailing as part of a programme to revive a demoralized country after World War II.

Sailing superstars such as Eric Tabarly emerged as heroes for this new interest in sailing, and over the decades a much more positive attitude to the sea and sailing in all its forms has resulted in 21st Century France being arguably the world’s sailing superpower in terms of the level of national involvement – every French schoolchild gets a minimum of a week of learning to sail every year – and the range of the sailing involved. There are many more major – and inevitably highly-sponsored - international offshore events from France than from any other country.

The pioneer. The memory of Eric Tabarly continues to be the great inspiration for French sailing development

The pioneer. The memory of Eric Tabarly continues to be the great inspiration for French sailing development

Within their own cohesive nation, they have the population, the level of economic activity and resources, and the official support to operate at this level. Ultimately, it’s the numbers game – population levels and concentrations of spending power need to be high to support such levels. Looking perhaps wistfully from small, under-developed Ireland, an Ireland where mounting any major sailing campaign has to overcome many hurdles which have been long since been dealt with on the Continent, we have only to remember that in another national example, the Dutch Olympic Sailing Team operates on a basic annual budget of €18 million, and their current rates of medal success reflect this.

The traditional image of Dutch sailing. They keep their classic vessels in superb order – yet they also fund their Olympic Sailing Team with a basic €18 million annual grant

The traditional image of Dutch sailing. They keep their classic vessels in superb order – yet they also fund their Olympic Sailing Team with a basic €18 million annual grant

Thus the French dominance is not total – many European nations have well-structured sailing development programmes – but it is France’s range of major events which is the unrivalled attraction for young offshore sailors keen to make their mark. And even in an event which theoretically should have been British through-and-through – the Golden Jubilee of the Golden Globe Non-Stop Round the World race of 1968-69 – it was France which stepped into the organisational breach through the keenly self-promoting port of Les Sables d’Olonne, ready and willing to take on the mantle of staging the challenge.

For Ireland’s Gregor McGuckin, an adventure sailor who has in recent years made his living in the sometimes humdrum world of many Transatlantic deliveries and in skippering a large charter yacht in the Caribbean, the Golden Globe was the Golden Opportunity to step up the ladder and show his true potential. Its re-enactment rules, which insisted on closed profile hull designs of boats designed no later than 1980, indicated a manageable budget even within the stringent security and safety requirements.

Yet in the Ireland of 2016-17-18, when McGregor was putting his campaign together, there were many other demands on the very limited national spend on promotion through sailing spectaculars. But a boost of support from Hanley Energy got McGuckin and his greatly-strengthened 1975-vintage Biscay 36 to the line at Les Sables-d’OLonne on July 1st, and the rest we know – he was battling with Tomy for third place when the Storm of Storms struck them, and in an area notorious for its stupendous pinnacle waves, both boats were taken out by 360 degree rolls with the almost inevitable dismasting, and Tomy was injured.

It speaks volumes for the high standards of safety and seaworthiness set by the organisers that now – with no less than three boats exiting the race in this violent way – all three boats have survived, with the first to go – Norway’s Are Wig – reaching Cape Town under jury rig without assistance.

As for Greg McGuckin’s Hanley Energy Endurance, she has been battened down in mid-ocean while her skipper was taken by the Osiris to remote Amsterdam Island for collection by the Royal Australian Navy’s HMAS Ballarat for onward transit to Perth, where he will arrive early next week.

HMAS Ballarat – Gregor McGuckin is now safely on board, and will arrive in Perth early next week

HMAS Ballarat – Gregor McGuckin is now safely on board, and will arrive in Perth early next week

Meanwhile the response from India to Abilash Tomy’s predicament has been fascinating, as it has revealed that he is a leading figure in a national programme for character-building through sea-going training and achievement, and his boat Thuriya – a beautifully-built replica of Robin Knox-Johnston's original Suhaili – is being retrieved from the open ocean by the Indian Navy for full restoration, while he personally is recovering from his injuries under the most expert medical treatment.

The rescue team from the Osiris alongside the dismasted Thuriya. The Indian Navy has announced that they will retrieve and restore the yacht.

The rescue team from the Osiris alongside the dismasted Thuriya. The Indian Navy has announced that they will retrieve and restore the yacht.

That India should be putting considerable government resources behind such a programme is thought-provoking for Ireland, as our private efforts in a similar direction are fragmented in the extreme, with several organisations and individuals always trying to delve into the same very limited sponsorship pool, and always doing so in the knowledge that if they do achieve support, then ultimately it will be in some foreign – and almost inevitably French – competitive event in which they have to prove themselves.

For sure, if the Atlantic Youth Trust raises the funds for its 40 m educational barquentine, that will be an Irish-based operation which will get away from the need for expensive headline-grabbing competitive sailing, while providing benefits in other directions. But the fact that the AYT’s efficient and obliging CEO Neil O’Hagan is also CEO of Team Ireland, the competitive organisation which has been supporting the racing of Enda O’Coineen, Joan Mulloy and Gregor McGuckin, gives us some idea of how thinly resources are spread.

"Team Ireland, in turn, finds itself competing with the Cork-based Ireland Ocean Racing for national support"

Team Ireland, in turn, finds itself competing with the Cork-based Ireland Ocean Racing for national support, and with the formidable talents of Nicholas “Nin” O’Leary as its star sailor and the Vendee Globe 2020 as a named possible objective, IOR has enormous potential. We can only hope that “doing good worth by stealth” is the background mantra, for it really would be like a breath of fresh air if a fully-funded campaign for any event was launched upon us completely-formed, rather than asking us to share in the exhausting twists and turns of the fund-raising process.

Either way, for would-be competitive international offshore racers starting from scratch, the route is inevitably through France, through the Mini-Transat, the Figaro Solo, the Open 40s, and the heady world of the IMOCA60s and the Vendee Globe, with all its lead-in races.

The new foiling Figaro 3 for 2019’s Golden Jubilee of the solo spectacular is now well into production

The new foiling Figaro 3 for 2019’s Golden Jubilee of the solo spectacular is now well into production

And even if you’re French, it takes time. Sebastien Simon, who won the recent Figaro Solo, has been so consistent that he already has an IMOCA 60 for the 2020 Vendee Globe in build, but his actual first overall win in 2018 was at his fifth attempt.

The Figaro will be even more competitive and expensive next year, its Golden Jubilee, when they’ll racing the foiling Figaros 3s for the first time. But so highly-rated is it as an event that just a stage win can be greatly to your credit – Ireland’s Damian Foxall launched himself on his stellar career with that one-stage-of-Figaro win. And though Tom Dolan of Meath - who has been fighting the good fight in French sailing since 2011in the Minitransats – had very mixed results in his first Figaro this year, when everything was falling into place for his boat Smurfit Kappa he was clearly competitive, and that’s what they notice with the rookies.

The great veteran – 73-year-old jean Luc van den Heede currently leads the Golden Globe Race by more than a thousand miles

The great veteran – 73-year-old jean Luc van den Heede currently leads the Golden Globe Race by more than a thousand miles

So if India is determined to pursue this programme of national strengthening through a developing sailing tradition, they would do well to look at France, and they probably already have many times. For we only have to reflect that the runaway leader in the Golden Globe is currently 73-year-old French deep-sea legend Jean-Luc van den Heede, who is doing it to crown out a remarkable offshore racing career, to appreciate the strength and depth of French sailing

And at the other age extreme, last November’s Minitransat was won by 20-year old Erwan le Draoulec. Until then, even the French had thought that a 20-year-old could not have developed the core stamina to win such a full-on marathon, but it seems he had.

Le Draoulec not only won, he won well. Yet afterwards – in very French style – he commented that he hadn’t really enjoyed the ferociously hard-driving day after day, as he felt that sailing across the Atlantic in this way was a sort of insult to the spirit of the great ocean……

The philosopher-sailor who won….20 year old Erwan le Draoulec had a stunning overall win in last November’s Minitransat, but on reflection afterwards, he thought that crossing the Atlantic at maximum speed in acute discomfort was disrespectful of the ocean.

The philosopher-sailor who won….20 year old Erwan le Draoulec had a stunning overall win in last November’s Minitransat, but on reflection afterwards, he thought that crossing the Atlantic at maximum speed in acute discomfort was disrespectful of the ocean.

Any nation which, through sailing, has lifted itself from the post-war glooms to the position where its senior sailors are still winning ocean marathons while its best young sailors can be philosophizing like this after winning a great race is surely very special. But in this week of all weeks, it is Greg McGuckin who is the special one. By his gallant gesture in the full horror of the Southern Ocean, he has done Ireland proud